ImpactAlpha, Aug. 31 – Tearing down part of a freeway was such a boon that Rochester, New York, is planning for removal of more of its 1950s-era Inner Loop highway.

It took nearly two decades and $22 million for Rochester to remove nearly one mile of the Inner Loop and recover nine acres of land for development. The project reunited the downtown area and outer neighborhoods, improved air quality and transportation options for citizens, and spurred the construction of mixed-used development and affordable housing over the former highway.

Five years later, that modest investment has yielded economic benefits of $229 million, according to one analysis. The advocacy organization Congress For The New Urbanism called the Inner Loop project “a positive precedent for freeway removal efforts around the U.S.”

As Rochester is getting ready to tear down more of its Inner Loop, other cities are following suit. In Las Vegas, Nashville, St. Paul and other metropolitan areas, city planners, social-justice activists, and sustainable-infrastructure groups are looking to repair communities torn apart by highways and other transit infrastructure.

A new federal program is providing much-needed funding for those efforts. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg called out “highways that have cut communities in two” and alluded to the structural racism embedded in so many mid-century interstates – supported by federal dollars.

“Reconnecting Communities,” part of the Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act, provides $195 million this year and $1 billion over its five-year life. Transportation analysts and public finance experts say the program could punch well above its weight, with transformative potential for communities and impactful opportunities for investors.

Reconnecting communities

In Nashville, Interstate 40 cut through a Black neighborhood in the 1960s, demolishing homes and businesses. In St. Paul, I-94 devastated a middle-class Black neighborhood, demolishing hundreds of homes and businesses. In Oakland, Calif., the Nimitz Freeway divided once vibrant Black neighborhoods before it collapsed in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake – and was rerouted.

With their hefty environmental footprint and historical weight, highways are clearly one of the most egregious examples of past infrastructure harms, says the National League of Cities’ Brittney Kohler. Ripping them out has the potential to be the most transformative.

The federal grant application suggests other approaches as well: “The variety of transformative solutions to knit communities back together can include: high-quality public transportation, infrastructure removal, pedestrian walkways and overpasses, capping over roadways, linear parks and trail connectors, roadway redesigns and complete streets conversions, and main street revitalization” (Reconnecting Communities grant applications are due October 13).

And removing highways altogether would almost certainly be one of the most expensive and laborious types of projects. Municipalities around the country are considering other options.

In Las Vegas, Charleston Blvd. slashes through the heart of the city, dividing east from west. The downtown underpass is now over 70 years old and deteriorating. By lowering it, city officials see an opportunity to connect the two halves of the city, improve public safety, make the area more livable, and promote development. The city forecasts the project will cost about $40 million, according to the National League of Cities

Nashville’s Jefferson Street Multimodal Cap and Connector project would cover parts of I-40 highway. Discussions about capping the road with community buildings and open space have been ongoing for nearly a decade. A 2021 estimate put the project cost at $120 million.

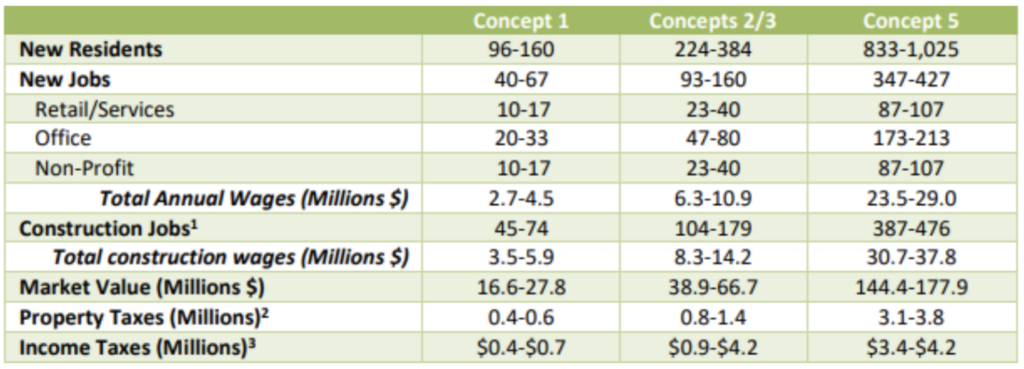

In St. Paul, Minnesota, the “ReConnect Rondo” project envisions an “African American cultural enterprise district” built on a land bridge over parts of I-94 through downtown. The highway, built between 1956 and 1968, devastated a middle-class Black neighborhood. A 2020 feasibility study forecasted sizable direct economic benefits from the project, not including indirect economic multipliers.

Even as removing highways that rammed destructively through minority neighborhoods decades ago seems to be having a moment, Louisiana is debating doing the opposite. The state is seeking to build a 4-mile stretch of I-49 through a historically Black section of Shreveport.

The “I-49 Inner City Connector,” estimated to cost in the hundreds of millions of dollars, has drawn criticism from both local community members and national advocates.

Municipal impact

Highway removal plans will require lots more money than what Reconnecting Communities can offer. State governments and other federal programs, including the pandemic-era American Rescue Plan, will fill some of the gap. Private funds will also be key.

Many of the various projects plan to complement federal funds by issuing municipal bonds, according to Emily Swenson Brock, director of the federal liaison efforts at the Governmental Finance Officers Association.

Despite higher interest rates, market conditions are favorable for muni issuers. Demand remains high and supply lean. Muni issues through July are down 13% compared to a year ago, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, and are on track for one of the lowest yearly totals of the past decade.

That’s in part because several rounds of COVID federal rescue funds have mitigated the need for many local governments to tap the bond market. Another factor: a general antipathy toward debt that’s lingered since the Great Recession.

Brock thinks the promise of Reconnecting Communities — the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for transformative infrastructure that rights past social justice wrongs — will overcome such concerns.

Public-private partnerships

Many communities that win Reconnecting Communities grants will likely also seek investors for public-private partnerships, or PPPs. The broader infrastructure bill specifically encourages communities to include a “Value for Money” analysis. That’s a “carrot” meant to encourage cities to be innovative, Brock says, with the Department of Transportation recognizing the need to find new ways of deploying private funds.

Public-private partnerships represent between 5% and 20% of total infrastructure outlays throughout the developed world, but only 1% to 2% of spending in the U.S., according to the advisory firm Baker Tilly, which called the provisions a “very exciting proposition.”

The need for new types of funding partnerships also stems from the novelty of Reconnecting Communities. The projects it envisions are the polar opposite of traditional transportation PPPs, which often depended on a fee-for-use model, like toll roads or parking meters. A private partner for a stretch of reclaimed municipal land might look more like a developer than a concessionaire, for example.

One useful model: “transit-oriented developments,” which center dense construction around urban transit hubs for more accessible, connected neighborhoods.

In addition to tapping the municipal bond market, localities can raise taxes, tap reserves, partner with developers or other private entities, and apply for some of the other federal grant programs now available.

Inclusive planning

Introducing the Reconnecting Communities program in June, Buttigieg called it a program designed to address the “consequences of past choices that live on to affect transportation today.” Given its unique mandate, the program faces some unusual headwinds.

One of the program’s knottiest components might be the need to bring the community along in planning. Applicants need to show not just that the proposed project will advance social equity, but that they will also need to incorporate into the planning process those who have been “underrepresented in decision-making in the past,” Brock says.

Social-justice groups and other community representatives may not share the same vision for the project. There may be concerns about gentrification and displacement, and as Transportation for America’s Stephen Coleman Kenny puts it, many residents of neighborhoods that were scarred in the past are “rightly distrustful” of state and federal government.

“This is a balancing act and a discussion that communities and their social justice partners should be holding,” says Kohler of the National League of Cities. Nonprofit entities like community land trusts or land banks could help ensure future value created by the development stays with the local community.

Governors and elected officials in New York have long supported the efforts in Rochester. In other states, red-blue divides between the cities undertaking the projects and their state legislatures could slow the projects.

“Fights with state governments are going to be a big part of whether these projects succeed,” Kenny says. In San Antonio, Texas, the city undertook a traffic calming project on a downtown thoroughfare with the blessing of the state, only to have the Texas Department of Transportation reverse its decision several years later. drawing scrutiny for their ability to stymie local development efforts.

“Community access to these programs is going to be transformational to our nation’s infrastructure,” Kohler said. The program “is going to be a fantastic opportunity to see how we can use transportation to help people.”

Check out all our coverage of Muni Impact, which is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Posts do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation.