When the University of Virginia issued the first Build America Bond ($250 million) in April of 2009, it was just about three months after the federal program was signed into law. Over the course of the next year and a half, more than $180 billion was raised for US infrastructure. The goals and policy objectives of the legislation – recovery of a marketplace that had stalled in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and support of American communities – were speedily met.

It has now been a year and a half since the ground-breaking Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, was signed into law and zero dollars of a key provision, the $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Emissions Fund, or GGRF, has been spent. The immediacy of global warming has been pressed upon the public tremendously over the last decade and has reached a zenith in the last three. Yet, this once in a generation moment “to mobilize financing and private capital to address the climate crisis,” as the government has explained the program, is itself lacking immediacy.

In addition, engagement with state and local governments has been lackluster and, while the creation of Community Development Finance Institutions, or CDFIs, is booming, the deployment of capital is not.

The juxtaposition of the Build America Bond program (market-oriented, led by state and local governments) to that of IRA’s GGRF (market-creating, led by new grant formulas, green banks and CDFIs) is jarring. Climate change requires solving problems at-scale and engaging financial infrastructure that works in large volume. The success of the IRA relies on the ability of states and local governments to access and deliver on these massive climate investments.

Using the municipal market not only leverages a well-paved financing vehicle but, considering the need for self-sustaining climate change partners for the long-term, state and local governments will be essential to leverage public wealth and assets for successful transition finance. More engagement is needed.

CDFIs are booming

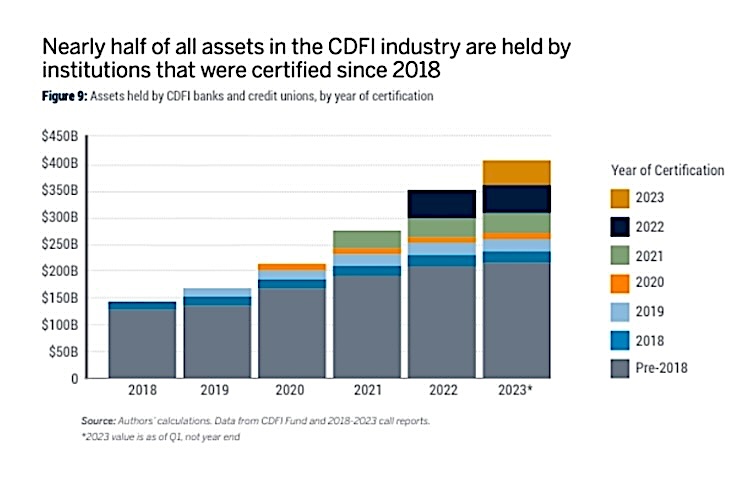

CDFI-certified entities have tripled over the last five years, in large part due to large federal programs coming out of the IRA and other Biden-era laws and policies (see figure showing growth during this administration, below). At the surface level, CDFIs align very well with IRA’s policy objectives as mission-oriented financing vehicles that are already very familiar with federal grant programs.

CDFIs were born in the recognition of the systemic lack of access to traditional finance faced by underserved communities. Historically, these communities, including low-income neighborhoods, minority populations and rural areas, have been excluded from essential financial services like loans, investments and financial education. This hinders their ability to build wealth, start business and improve their economic well-being.

Recognizing this injustice, CDFIs were seeded not just as financial institutions but as mission-driven organizations. Their core principle is to bridge the gap between traditional finance and underserved communities prioritizing social and environmental impact alongside financial return.

CDFIs have taken the helm in response to what the IRA is looking to achieve. Some of the largest portions of the bill, the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, the Neighborhood Access to Solar, and the State and Local Climate Action Grant Program, all explicitly mention CDFIs as eligible grantees. While the IRA does not rely solely on CDFIs (much is channeled through state and local governments, consumer and businesses), it presents significant opportunities for their involvement across various programs.

And the business of CDFIs is largely a grant or a government business. Whether their funding is from foundations, government agencies or from the Treasury CDFI fund, CDFIs have an intimate understanding of grant writing, which makes them quite capable of filling in the gaps made by the IRA much quicker than other stakeholders or potential beneficiaries from the massive amount of funds soon-to-be dispersed by the federal government.

Capacity, reach and coordination

While CDFIs play a critical role in community development, IRA is over-reliant on this segment of the financial world considering the scale and complexity of its goals. Two initial areas where the IRA’s reliance on CDFIs portends problems: size and reach.

CDFIs pale in size compared to what is planned for: the median size of a CDFI loan fund is $13.8 million, and a credit union is $174 million. The National Clean Investment Fund, or NCIF, is $14 billion.

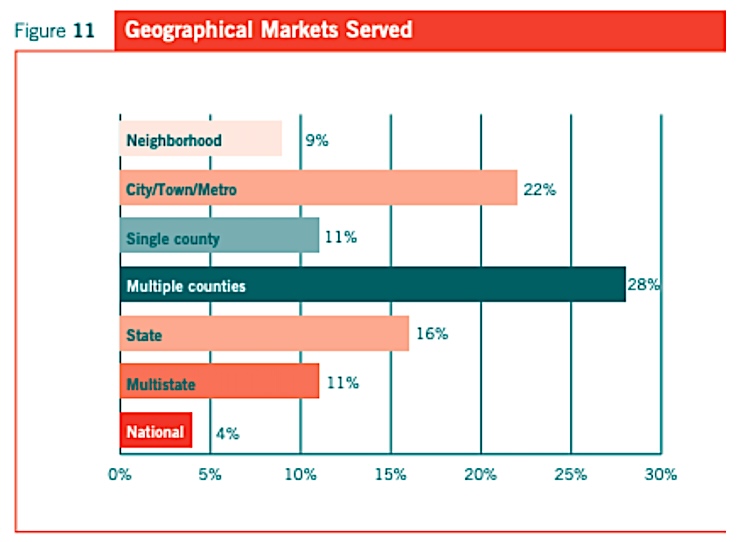

Broadly, CDFIs are focused on micro-finance, not large-scale, globally significant finance. Adding to the lack of reach, 85% of CDFIs are licensed to operate in a single state (see figure below). The EPA is currently making arguments before the US Supreme Court on inter-state issues.

Additionally, the fast growth of the CDFI community has created operational headaches for many of these organizations, including the competition for staff and the need to better understand the technical aspects of climate issues, given that most CDFIs have a focus on income inequality and not greenhouse gasses.

What has transpired is that consortiums of community lenders have been built to collectively bid on large portions of the GGRF funding. In theory this is more efficient for the federal government, but these consortiums of hundreds of entities will require a very high level of internal organization.

Take a look at Climate United, a consortium of more than 350 communities and capital partners that has submitted a bid to manage part of NFIC. Aside from green banks, there are no state- and local government-financed partners, nor entities that are directly engaged in community finance through the municipal bond market – the principal way in which infrastructure finance occurs in this country. This is a mistake.

While CDFIs play a vital role in community development, their ability to handle large-scale implementation of complex programs like those in the IRA may be limited by capacity, reach, expertise, and existing resources. These limitations highlight the need for more engagement with green and non-green state bond banks but also with market participants that engage in the municipal bond market wherein about $40 billion a month is raised for public infrastructure at present.

Eventually, many projects will weigh into this marketplace. But as it now stands these are afterthoughts, not part of the current plans. In order to put IRA shovels in the ground quickly, it would behoove consortiums bidding on various components of IRA to consider financing avenues that are already well paved.

The power of what is in place

Stakeholders are leveraging CDFIs and green banks as the principal means in which to make the IRA’s GGRF goals a reality. Yet, these entities are not agents of at-scale change and this approach will be stymied without thorough engagement by state and local governments. CDFIs tend to be hyper-locally focused and have little incentive or need to engage with state or local government financing entities, as their capitalization comes from elsewhere. This micro-development focus functions well to meet local needs and challenges but will be hindered in scaling and the needed standardization of problem solving for climate change.

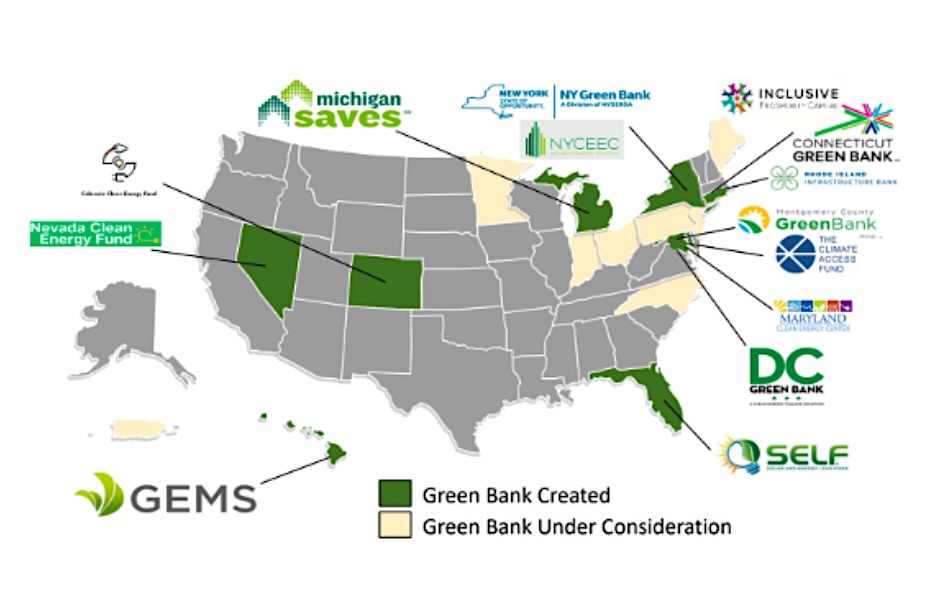

Green banks make more sense as they are financing vehicles of the state or local government directly and encourage cooperation amongst public and private interests. Still, with a few exceptions (California and Connecticut are the most notable), green banks are few and far between in this country, mostly located in the Northeast (and most are new in the last few years meaning experience is lacking). This is not ideal.

For IRA to succeed and do so quickly, engagement with the state and local finance arms that are active in markets makes sense. States with bond banks in place are in better position to take advantage of IRA grants. While green banks have been in the climate-oriented news, many don’t realize that at least 15 states have bond banks that have existed for decades. These entities pool local government loans and issue municipal bonds to support local projects. This type of infrastructure that is already in place should be leveraged. There should be more communication between these state-level organizations and the various consortiums responding to the federal call-to-action.

States that do not have bond banks do have state and local financing institutions that access the municipal market in any number of sectors that overlap with IRA (housing, transportation, health and human services for example). Identifying these government agencies and levering their ability to raise capital through the muni market is sensical.

Further, given the price tag of transition finance ($27 trillion according to McKinsey), there is discussion on the self-sufficiency (and profitability) of these financing programs as IRA funding phases out. Philanthropic support and private capital will be catalytic but not feasible for decades at the pace it is needed. Buy-in from state and local government agencies that are willing to commit financial obligations backed by income taxes, sales taxes and liens on physical assets will be needed for a full transition to zero. This engagement should begin now.

Some take-aways:

Where state and local governments are underprepared for the scale and nuance of IRA:

- Limited local government capacity: Navigating the numerous programs, grants and tax incentives requires resources many local governments lack. This will lead to missed opportunities and inequitable access to benefits.

- Uncertainty about green banks: New green bank programs offer financing, but details remain unclear, making it difficult for local governments to plan their involvement.

- Complex communication: Local governments need to effectively communicate the available IRA programs to residents and businesses, which can be challenging and lead to unequal uptake.

- Limited state law authority: Some local governments lack the authority to implement certain IRA provisions due to pre-emption by state laws.

A few areas where improvements would go a long way:

- Increase federal and state technical assistance: Provide resources and expertise to help local governments navigate the IRA’s complexities, including grant writing, project development, and outreach. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy has done work here.

- Develop shared resources: Create clear, accessible information about IRA programs for both local governments and communities. Milken Institute has done work here.

- Offer dedicated funding for local government planning: Similar to the Climate Pollution Reduction Grant program, provide resources for local governments to identify and develop competitive grant proposals.

- Address state law limitations: Advocate for changes to state laws that hinder local climate action efforts.