The financial history of extraction, enslavement, and predatory greed have been heavy on our minds when designing the new investment strategy for the Kataly Foundation.

The Kataly Foundation is a philanthropic organization rooted in non-extraction, wealth redistribution and power-building in Black, Indigenous, and all communities of color.

Yet our work still requires that we participate in traditional (extractive) financial systems. Ultimately, we hope to work within the system in order to transform it, in support of our grantee partners.

This series has focused on the questions and decisions behind Kataly’s investment strategy. These decisions are complicated because our global financial system is inherently unjust and inequitable, and operating within it always requires some kind of compromise. Knowing the history, data and evidence and continuing to invest in public equities and trust large financial institutions to make measured risk assessments is both misinformed and misaligned with racial justice values.

These institutions continue to see the communities we serve as a profit center rather than as people with brilliant ideas and families with hopes for their children.

In this piece, we will share the history and context that created today’s financial system—a story of corporate greed, the hoarding of wealth, and predatory practices. It is also the story of how Black communities in particular have been central targets of that greed.

And we’ll also begin to share our thoughts for the next chapter, including a strategy of blended returns between public and private asset classes in order to support financial institutions that are rooted in community and not in enslavement. And serving our grantees by using an organizer and activism lens in our investment strategy.

Our hope is that others who are responsible for setting investment strategies at their respective foundations who have also made a commitment to racial justice will engage with us. The more of us who ask these questions and keep these nuances and historical context in mind when we make investment decisions, the more possibility there is for real change.

Slave markets

The first modern stock market was created in Amsterdam in 1611 to sell shares in the Dutch East India Company, which funded colonization and enslavement. For the first time, shares could be traded multiple times, increasing or decreasing in value to the owner, depending on the value at the time of the trade.

This public market for company ownership created something new: the right to a future economic benefit. This was a shift—rather than using capital in order to own and sell goods, people were now able to also own and sell capital. Goods are finite, while creating money that creates more money can be infinite.

Thus began modern day investing and exponential wealth accumulation.

The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) followed in the 1790s and became and remains the epicenter of finance. To understand its history, it’s important to understand that the American South, in 1860 and if it had been a separate nation, would have been the fourth-richest nation in the world.

Most of the financial products that were needed to finance these Southern corporations (because let’s be clear, these plantations were corporations), such as deposit accounts, loans, property insurance, foreign exchange, and capital raising, were funded through the NYSE. Enslavement was so tied to New York’s prosperity that it proposed seceding from both the North and the South to protect its economic interests.

In this context, property insurance did not only mean the land and the equipment, it also meant treating enslaved people as property, which is how modern day collateral was created.

In the present-day context, every major financial institution—Citigroup, Wells Fargo, JP Morgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley—have acquired financial institutions that existed pre-1860s. That means each has benefited from the enslavement of stolen Africans.

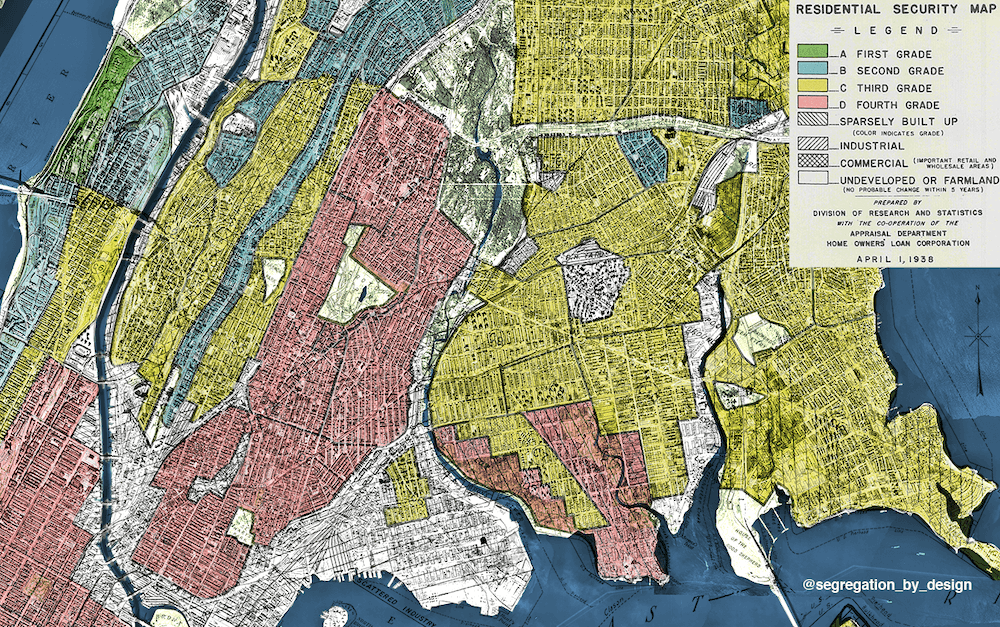

And their culpability is not limited to the history they inherited. During the 2008 financial crisis, regulated and unregulated lenders targeted traditionally Black and brown neighborhoods to sell toxic mortgage products. These neighborhoods were easy to target because of historic redlining, where the federal government restricted mortgages to Black people and blocked investments in Black neighborhoods.

Predatory lenders forced mostly people of color into subprime mortgages, specifically Black women. Many could afford traditional loans with favorable terms. Because these lenders were largely unregulated, they foreclosed on homes quicker and without care for the people they were dispossessing.

Wall Street showed no interest in alleviating people’s losses because most corporations had already made their profit off of these faulty mortgages through securitization.

When the housing market crashed, the government used public taxpayer dollars to bail them out, despite their terrible risk management decisions and their destructive greed. But once again, Black people lost the most, with Black families losing 53% of their wealth vs. white families who lost 17%.

Mispriced risk

In 2009-2009, the damage wasn’t just the loss of previous wealth, but also the loss of future wealth because of the pervasive and false narrative that Black and brown communities were riskier to invest in.

Before the great recession, these communities were specifically targeted with subprime mortgages that had unfavorable terms and overall higher interest rates than white families. During this period, most mortgage lending was for refinancing existing homeowner loans and not new loans for homeowners. When the housing bubble burst, Black communities were in a more precarious position, not because they themselves were a higher credit risk, but because the mortgage products they were sold were inherently riskier.

Fast forward to 2023 and who gets to fail? The same people who failed in 2008. When Silicon Valley Bank failed, the focus was protecting mainly white, wealthy depositors, and investors from losing their money despite the bank failing at basic risk management and again, thinking that growth could continue indefinitely.

There’s no discussion about the demographics of the depositors that ran Silicon Valley Bank; or of the executives that ran Wachovia or Lehman’s as being bad managers or riskier at making business decisions.

This history of extraction, enslavement, and predatory greed have been heavy on our minds when designing the new investment strategy for the Foundation, and many questions have come up for us along the way.

If we must place our assets in financial markets:

- How can we go beyond environmental, social, and governance (ESG) funds and examine investments through a justice lens?

- How can we support companies that acknowledge and take action to ensure diversity and racial equity?

- How can we look at a blended return between public and private asset classes as a strategy to be able to support financial institutions that are rooted in community and not in enslavement?

- How can we use an organizer and activism lens in our investment strategy, and be in service to our grantees?

There are no simple answers. If we are being honest with ourselves, we know that there is no completely morally sound way to use the tools of an inherently racist and unjust system.

So we are left with the thorny challenge of finding the best possible way forward that allows us to support our grantee partners’ work, doesn’t cause further harm and allows for much-needed transformation within the financial system.

Lynne Hoey is chief investment officer at the Kataly Foundation.