(Editor’s note: The insights in this article reflect the work of a diverse array of Catalytic Capital Consortium partners. The outputs of this work can be found on the C3 website. With support from the consortium, ImpactAlpha has published hundreds of stories on the application of catalytic capital.)

Some capital gaps are transient and can be bridged with seeding or scaling catalytic capital. Other gaps are structural and require sustaining catalytic capital. And some gaps are layered together, even in the same market or sector.

For catalytic investors, the differences are important because we need to be clear on the capital gaps that we are targeting in order to deploy catalytic capital accurately and efficiently, with minimal waste and distortion to areas beyond those gaps.

Since 2019, the Catalytic Capital Consortium, or C3, has been working to build the field of catalytic capital, including funding a range of efforts that build an evidence base for capital gaps around the world. That evidence base now includes many cases of how catalytic capital has already been deployed to meet those needs.

For example, common sense and research suggest that conversions to employee ownership in the US should become more investable as investor experience, track records, and understanding of the mechanisms grow. However, deal structures that give priority to worker-owners rather than to outside investors may clash with prevailing norms in mainstream finance and face a persistent structural capital gap.

Debunking myths

As senior advisor to C3, I have been reviewing and reflecting on the rich findings that have been produced, as well as complementary efforts across the field. The first part of this synthesis, “5 Myths Preventing Catalytic Capital From Going Where It’s Needed,” was published in Stanford Social Innovation Review earlier this year. To recap:

Myth #1: Gaps only occur in poorer, less economically developed parts of the world. While there are indeed pervasive gaps in poorer parts of the world, the reality is there is a huge diversity of capital gaps out there including in advanced economies with abundant capital and sophisticated financial sectors.

Gaps persist around rental housing in Europe, “hard tech” climate ventures, and BIPOC-owned businesses in the USA, just as much as they do around SMEs in Africa.

Myth #2: Gaps are easy to spot—just look for the absence of capital available to potential investees. In many gaps, capital is available but not in the amounts, and/or on terms and conditions, appropriate to the investee.

This is recognized in the IFC’s analysis of the MSME finance gap, which considers barriers for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, such as complex application procedures, unfavorable interest rates, high collateral requirements, and insufficient loan size and maturity.

Research in Ghana confirms that catalytic capital is distinguished by provision of non-traditional terms and longer financing timelines, much more than concessionary pricing.

Myth #3: Gaps stem only from weaknesses on the part of potential investees. In the prevailing power dynamic, enterprises and communities are simply labelled “hard to reach” without the necessary questioning of why investors are “reluctant to serve.”

In truth, capital gaps result from misalignments between investors’ knowledge, attitudes, requirements and expectations, and investees’ profile, situation, values, and wider context (which in turn drive their needs and constraints). Recognizing this is critical, because the work of closing capital gaps typically requires change on both the demand and supply sides.

Myth #4: The gaps faced by innovative solutions are greatest at the outset and gradually narrow as they scale. Some capital gaps are expected to persist in the long run (structural gaps), while others might narrow or even close over time (transient gaps), typically around novel solutions, models that carry a high degree of “early-stage risk” and lack track record.

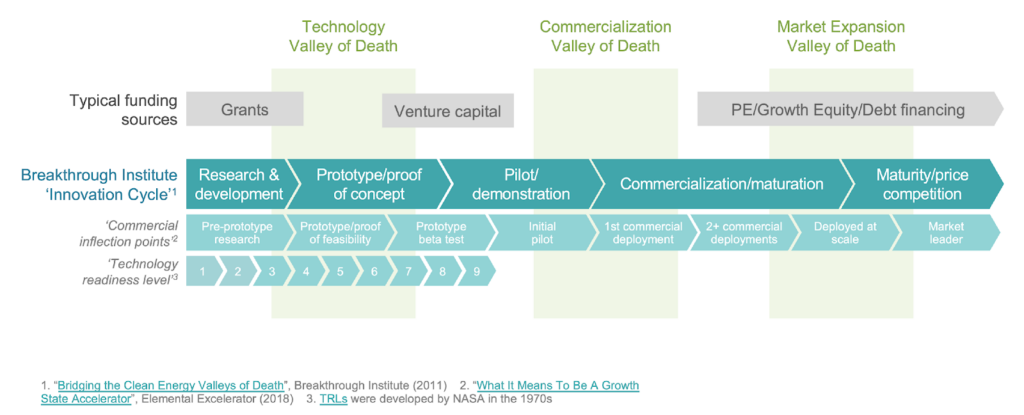

But real-world scaling journeys often involve expansion into new areas that bring greater risks and/or costs. It is not unusual for second funds to require more catalytic capital, not less. Examples include Women’s World Banking Capital Partners Fund II and ResponsAbility’s Energy Access Fund. Prime Coalition has identified at least three discrete “Valleys of Death” in the development journey of ‘hard tech’ climate ventures, relating to technology, commercialization and market expansion.

Myth #5: Attitudes and values are not relevant to capital gaps. Capital gaps can open up because of misalignments in attitudes and values between supply and demand.

In India, mainstream investors’ inability to accept differing work norms in artisan producer communities is a key factor leading to a lack of investment in impact enterprises working with those communities. This includes factors such as work flowing around family and community priorities (such as religious observances) rather than the other way around, and distributed methods of production and management in homes rather than in conventional factories.

In many Indigenous communities, wealth is defined not only as financial success but also social wellbeing, community health, continuity of cultural practices, or environmental connection.

Mainstream investors’ lack of understanding and acceptance of this can lead to capital being offered in ways and on terms that do not align with community norms, or to capital not being offered at all because of the perception that working with these communities is too difficult or costly.

Diving deeper into capital gaps

As we at C3 reflected on the findings from the Evidence Base projects, we noticed something else. In many commonly discussed markets and market segments, the reality is not that it is either a transient or a structural capital gap. Transient and structural gaps are often found to be layered together.

The example of conversions to employee ownership in the US is a case in point. In “Creating Shared Value,” research from MSI Integrity, Noah Klein-Markman suggests that employee ownership conversions in the US may gradually become more investable as more investor experience, track record, and understanding are built.

However, some worker-ownership conversions could see a persistent structural gap. These could include “non-extractive deal structures” where the distribution of profits is done with priority given to worker-owners rather than to outside investors. While this approach represents a powerful way to foster more equitable and resilient economic outcomes for workers – protecting them especially in leaner times – it also clashes with prevailing norms in mainstream finance.

Or take small and medium-sized healthcare enterprises in Africa. It’s plausible that the gap could be closed over time for some of these SMEs. We might expect these to be the ones that are larger, have more capable leadership, have more capital initially or are in urban locations with higher population density and easier access to team talent. Because the market segment is heterogeneous, it is not possible to have one uniform determination of whether the capital gap is structural or transient.

This dynamic is also borne out by global microfinance institutions over the past few decades. In emerging markets, many mature, regulated microfinance institutions, or MFIs, have developed to the point where they are able to attract and rely on commercial capital; some younger MFIs might still be in the process of scaling and require scaling catalytic capital.

Others within the same financial inclusion sector are MFIs (often unregulated) that intentionally target the most difficult geographies (such as fragile states or low-income states), the hardest-to-reach clients (such as the poorest or most rural population segments), and/or the most challenging (sub-)sectors or business models (such as small agricultural enterprises). These are the MFIs that typically require sustaining catalytic capital in the long term.

We need to be cognizant of the various sub-segments that exist within commonly discussed market segments, and that misalignments could be easier or faster to fix in some than others.

With transient gaps, resolving our target more clearly (say, larger urban healthcare enterprises) also leads to us better understanding the specific factors and contextual realities that are driving capital gaps. That puts us into a better position to decide whether and how to work on them to try to close transient gaps over time.

If we are indeed working to try to close transient gaps, having a clearer focus allows us to better track and assess how we are doing. For example, there might appear to be disappointingly slow change at the level of all healthcare SMEs, but accelerating change for larger urban healthcare SMEs.

Understanding that structural gaps are likely to persist in some parts of the market leads us to correctly recognize the importance of sustaining catalytic capital. Incorrectly assuming that the entire market or market segment can graduate to mainstream capital over time can have harmful effects by signalling that sustaining catalytic capital is not needed (or perhaps even distorting) as well as by placing unrealistic expectations and pressures on investees.

Driving investor impact

One of the characteristics of catalytic capital is that of ‘additionality.’ Essentially, that means you are enabling something that otherwise would not be achieved. That is, it achieves something ‘additional’ to what the general pool of capital does.

Recent work by the Impact Finance Research Consortium (Wharton, HBS, Booth) confirms that additionality is a key hallmark of catalytic capital investors, alongside a more flexible framework for financial performance. This is not engaging in different impact activities, but instead applying a different standard: To what extent would the impact have happened anyway without the investor’s specific contribution?

Investor contribution is the other way that this concept has been articulated and advanced. That framework can help to push the discussion further because it asks directly: What are you as an investor (as opposed to the investee) contributing to overall change that benefits people and planet?

Discussion about the ‘impact’ in impact investing most commonly refers to impact generated by the investee. There is little discussion about whether investors’ choices and actions are adding to (or indeed subtracting from) this impact.

What are the levers available to investors to contribute in this way? A recent case study of British International Investment’s approach to investor contribution by Impact Frontiers describes how this is approached across three areas of additionality.

Financial additionality. The first and most obvious is through the choices made in allocating and managing capital. This provides capital that others would not, in pursuit of greater impact than would otherwise be achieved.

This includes both the quantity of capital and quality (terms) provided. Terms could include interest rates (for debt) or enterprise valuation (for equity); tenor of the loan (for debt) or intended investment period (for equity); grace periods or flexible amortization schedules; mezzanine or innovative structures that the private sector doesn’t provide to that client; and flexible collateral requirements.

In-depth discussions with catalytic capital investors in the C3 Learning Labs add further nuance to this discussion. Investors have highlighted how timing (e.g., coming into a first-time manager’s fund early and allowing the manager to reference the early commitment) and quantum (e.g., providing substantial amounts that help managers reach certain thresholds needed to achieve the viability of the fund and a close, or to attract further investors) can be significant aspects of financial additionality.

Value additionality. This includes adding value beyond capital, such as by bringing needed expertise or partnerships, helping to enhance the investee’s reputation, or using investor influence to safeguard mission (including on an investee’s board). These levers can be used in ways that contribute to greater impact. These changes to impact can relate to outcomes, greater scale, greater depth/duration, more underserved stakeholders.

Capital mobilization. To what extent is the investor mobilizing additional capital from other sources into the same capital gap? This might occur in the same transaction (e.g., in a blended finance structure), or through multiple transactions into the same investee (including sequential transactions over time). This could also involve subsequent investments into multiple investees that are all caught in the same capital gap, but it will be harder to establish causal relationships with less proximate subsequent investments.

It is important to note that BII’s assessment of their investor contribution is not based on a binary outcome measure. To analyze their contribution, they assess each of the three elements of contribution (financial additionality, value additionality, and capital mobilization), as well as stating their confidence in those assessments and the scale at which they are expected to occur. This is, at least in part, a necessarily qualitative and subjective analysis.

The three areas are not entirely independent, of course. For instance, in a blended finance deal, flexibility on terms attached to catalytic capital (i.e., financial additionality) and lending one’s reputation to help signal a new fund manager’s credibility (i.e., value additionality) might be instrumental in achieving the ultimate level of capital mobilization.

Emerging frameworks and practices

A related piece of work is Impact Frontiers work on Investor Contribution 2.0, which highlights the need to connect the decisions and actions one is taking as an investor, to what is ultimately achieved for the investee and communities and stakeholders served, against the counterfactual of what otherwise could have been achieved under general market conditions.

As reflected in this template, this approach…

… Threads actions at the investor/investment level through company-level changes to ultimate changes for stakeholders and natural environment

… Compares the proposed investment scenario with a counterfactual (‘most likely alternative scenario’), and…

… Is based on reasoning and narrative, which is highly qualitative but allows logic to be laid out, evidence adduced, and all of it to be discussed and challenged as necessary.

Screening for additionality

So, how to screen investment opportunities for additionality? One interesting practice from Prime Coalition is to consult conventional investors as part of the process: Prime has convened an Investor Advisory Committee comprised of conventional investors interested in the same themes and markets. Prime puts potential investments in front of the committee to both gain confidence that Prime’s catalytic intervention will be a bridge to somewhere in terms of follow-on investment, and also to validate that the company will likely struggle to raise sufficient financial support without catalytic capital. Prime puts the committee’s evaluation alongside circumstances of the investment round and historical investment activity data to compile its full “additionality assessment” on a deal by deal basis.

The venture capital management company Prime founded, Azolla Ventures, has tracked investment outcomes to see if Prime’s approach to screening for additionality is supported by later observations, specifically whether or not ventures would or would not be able to raise capital without a catalytic intervention; the managers have done this by tracking the ventures that they did not invest in. Of the companies that passed the additionality criterion (i.e., they were not expected to raise capital without Prime’s catalytic intervention), 83% of those companies failed to raise capital within six months, validating the Investor Advisory Committee’s assessment.

Of the ventures that did not pass the additionality criterion (i.e., they were expected to be successful in their fundraising), 64% were successful as predicted and only five failed to do so. Taken together over the past ten years, the predictive power of Prime’s additionality committee could be said to be 78% accurate within the time frame of six months post-assessment.

Recent work by the University of Zurich and Roots of Impact points us to another useful lens on additionality: the perspective of the entrepreneur receiving investment. By asking the entrepreneur to describe what capital investment they have received that has been most pivotal in their journey, the team illuminated aspects of catalytic capital beyond flexibility around risk, return and timeframe, to encompass attributes such as respect, relevant sector/geographic experience, and trust in the entrepreneur’s vision.

Some investors also support complementary actions at the market level that are not part of the investment transactions per se. These are typically not seen as a part of additionality or investor contribution, but could be thought to contribute to a more strategic aim of closing market-level capital gaps.

One example of this is Invest for Impact Nepal, a pioneering partnership between a number of DFIs and development partners that is connecting Nepalese financial institutions and private equity and venture capital funds to access resources and expertise from development finance institutions and impact investors for investment into Nepali businesses and develop the emerging investment ecosystem.

The need for such ecosystem development is underscored by analysis undertaken by the Urban Institute in looking at catalytic capital flows and impacts in Cleveland, Ohio. This work highlights how the “capital absorption capacity” of places—the ability of communities to make effective use of different forms of capital to provide needed goods and services to the underserved—depends on the ecosystem of players beyond capital providers, that help to plan for, identify, coordinate, develop, and manage a pipeline of deals.

What is particularly striking from these findings is how ecosystem strength affects flows at as granular a scale as neighborhoods: some of Cleveland’s most distressed neighborhoods are found in the east side of the city, in the interstitial space that lies just outside the orbit of both major downtown anchor institutions and the University Circle anchor institutions.

An additional nuance to this is that market development is not only about driving investment flows and market scale at any cost. Recent work by the Center for Financial Inclusion shows how booming markets without adequate safeguards can be breeding grounds for predatory practices, giving the example of the digital credit market in Kenya.

The same report also highlights how investors can help to address these challenges. For instance, Community Investment Management in the US not only provides capacity building for their investee companies to make lending transparent and more affordable to the end consumers, but also contributes to shaping more responsible policy and lending practices at the market level, including co-founding the Small Business Borrowers’ Bill of Rights in 2021.

Minimizing subsidies

Wherever subsidized capital is provided to the market, given its relative scarcity, there is a need to strive for efficiency of subsidy at any given level of additionality.

A clear subsidy is not always present in catalytic capital transactions. Findings from the IIGhana/Ashesi study of catalytic capital deployment in Ghana to date emphasize that adapting non-price terms and conditions (such as collateral requirements) and demonstrating greater patience (i.e., accepting a longer duration) are far more commonplace as hallmarks of catalytic capital investing than pricing concessionality per se.

Where there is a price subsidy, how does one try to establish the efficient level of subsidy?

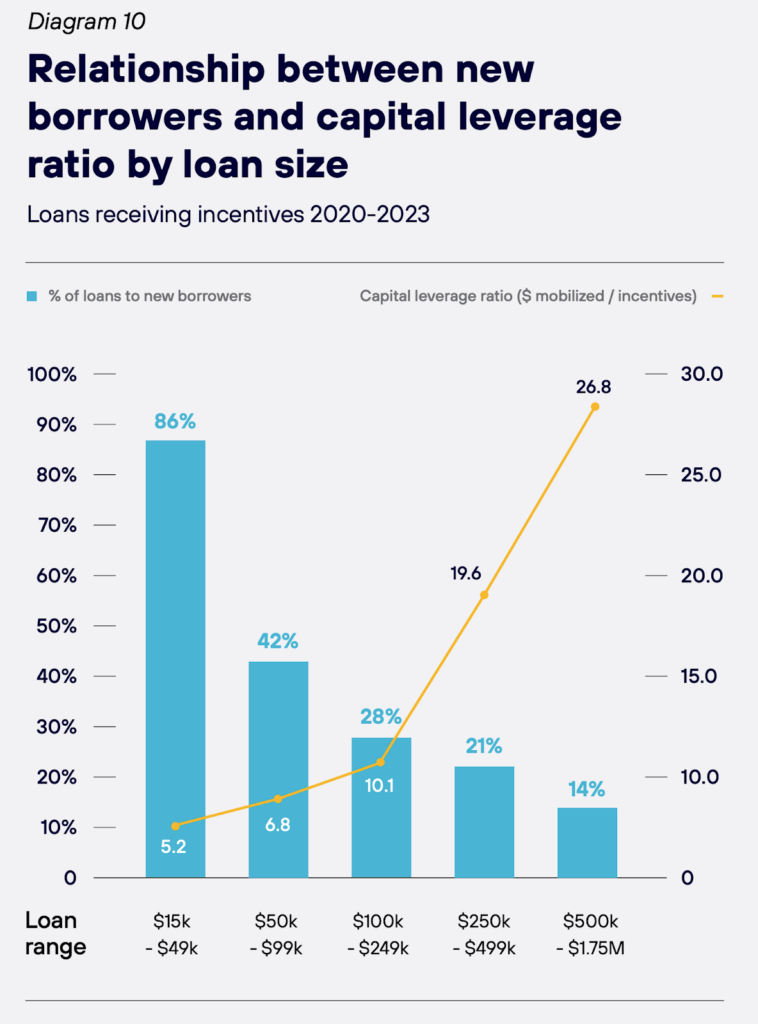

One promising innovative method of discovery is Aceli Africa’s approach. Aceli Africa incentivizes incremental lending by banks and other local lenders to agri-SMEs, with incentives geared to favor the least served and most impactful segments of the market. Aceli does this by fixing the range of subsidies on offer, and then tracking the “depth of additionality” as well as further capital mobilized (two key aspects of additionality) when deployed with a ‘competitive’ field of on-lenders. Aceli has now analyzed and published data from the first three years of this work. The chart below uses the proportion of loans to new borrowers as a proxy for depth of additionality.

The chart shows an inverse relationship between these two key aspects of additionality. The depth of additionality (as proxied by % of new borrowers) decreases as the level of capital mobilization increases. As such, the ‘leverage ratio’ (of third-party capital mobilized to incentive subsidies) changes dramatically as one moves from smaller loans (mostly to new borrowers) to larger loans (mostly to those who have borrowed before).

One caveat to note: the relationship in the chart is partly explained by the design of the instrument, since Aceli does offer higher levels of incentives for new borrowers, while new borrowers also tend to take out smaller loans.

This underscores the need to detail and nuance any discussion about efficient subsidy use. It also highlights the importance of devoting attention and effort to tracking depth of additionality, which is typically less visible and harder to track than third-party capital mobilization.

Without this balance, the obvious danger would be to maximize capital mobilization while compromising the intention to reach further and deeper into the capital gap and underserved needs.

Knowledge and understanding are critical to aligning the efforts required from all the different actors that are needed to address these gaps and drive impact at scale—from asset owners, asset managers and advisors, to incubators, advisory support providers and researchers.

I and others in the C3 community will be continuing to work to advance this work—including developing better tools for investors to assess capital gaps and drive investment strategy and parameters from that—through 2024, and we look forward to engaging many of you in that effort!

Harvey Koh is an independent consultant currently serving as senior advisor to the Catalytic Capital Consortium, Dalberg and FSG.