Editor’s note: ImpactAlpha contributing editor Imogen Rose-Smith, a longtime senior writer for Institutional Investor, contributes a bi-weekly column on the policies, practices and strategies of the largest asset allocators, including pensions, foundations, and endowments. As Imogen says, she’s “tracking what investors do, not just what they say.”

ImpactAlpha, Dec. 16 – I might have grown up in the U.K. but I have zero interest in cricket. A game somehow even more dull than already-boring baseball (sorry). I don’t understand the rules or how games can go on for days. Or even why.

I do, however, know a bit about discrimination.

So, it has been striking, and heartbreaking, to see the unfolding scandal in English cricket. And the story of racism and discrimination against players of Pakistani and Indian descent contains warnings for the asset management and financial services industry as well, as it grapples with diversity, equity, and inclusion in its ranks in a post-George Floyd, post #MeToo world.

Because what on England’s cricket fields shows is that when it comes to combating issues of systemic discrimination, tokenism and a tick-the-box approach does not work. What is required is a top-down, bottom-up commitment to a culture of inclusion. Absent that, efforts at diversity, equity and inclusion, or DEI, not only fail but calcify, and become part of the very problem they claim to correct.

Those lessons are particularly timely as the diversity problem in asset management has caught the attention of the U.S. Congress.

This month, the House Committee on Financial Services, which is chaired by staunch DEI advocate Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.), issued Diversity and Inclusion: Holding America’s Largest Investment Firms Accountable. Major investment firms made very public commitments to DEI in the aftermath of the 2020 police murder of George Floyd, which sparked wide protests against systemic racism. The report found “the diversity and inclusion of investment firms did not increase substantially between 2019 and 2020.”

Women, for example, made up 27.5% of executives at major asset management firms in 2020, up from 26.2 % in 2019. People of color made up 17.6% of the executive workforce last year, compared to 16.6% in 2019. The representation of Black asset management executives rose to 3.4%, from 3.0%; Latinos’ share went from 3.0% to 3.2%. “While some progress has been made over the last five years, there is more work to be done,” was the report’s understated assessment.

The findings of the Knight Foundation’s Diversity in Asset Management project were even more dismal. As of 2021, Knight found, diverse-owned firms represent just 1.4% of U.S. based assets under management.

For those willing to cut the investment management industry some slack for a slow start after George Floyd’s 2020 killing, remember that the investment management industry, including many of largest asset managers which cater to the public pension plan community, have for years – decades – said they are working on this problem.

The sea change in public consciousness over the past two years has awoken even the most rarified parts of the asset management industry to the fact that theirs is a “pale, male, stale and straight” world, as the Bank of London’s Anthony Watson put it.

The universal commitment to do better is reflected in the diversity commitments cropping up all over the place. In asset management, including among foundations and endowments, hedge funds and private equity, DEI is the new, er, black.

As my former Institutional Investor magazine colleague Leanna Orr pointed out on Twitter, the reality of finance is a slap in the face to these good intentions. Orr juxtaposed a screenshot of the investment team at Washington University in St. Louis alongside the office’s stated commitment to diversity. The picture speaks for itself. While there is some ethnic diversity among the team, every single person at the time was male. The majority of people in senior leadership roles, including the CIO and deputy CIO, are white.

Insider’s club

Orr says – and I know, I’m as shocked as you are – that she received significant pushback on social media for her tweet. Others, including another Institutional Investor alum Nathanial Baker, observed that the Washington University in St Louis endowment office was in fact more diverse than many such offices in the industry. (The university has since updated its website to reflect at least one female member on its investment team.)

Here is a fun (and by fun, I mean depressing) party game to play, right in time for the holiday season! Pull up the website for the investment office of any university endowment or outsourced CIO business. Read their diversity statement. Then take a look at the diversity of their investment team (because investing is where the true power is). Look, in particular, at the leadership of that team. If they do have women and/or underrepresented minorities on their team, when did those people join? Was it within the last two years? How senior are they? How long do they stay? (Extra points if you use the WayBack Machine.)

The diversity problems at university endowments run deeper than gender, race and ethnicity. University investment offices pride themselves on hiring a certain type of person. This typically means people with Ivy League, or equivalent, educational credentials and probably, though not certainly a Liberal Arts degree, perhaps an MBA, and a preppy background. They may have been on the varsity lacrosse team. Many are alumni of the very college they are working for. It’s an insiders club that favors home team players.

Take, for example, the team page of Yale University’s investment office, the epicenter for the endowment community’s talent breeding ground going back 30 years. Under the hugely successful leadership of David Swenson, Yale prided itself on hiring a certain type of person: young, smart, typically a Yale graduate. And that’s what the office is made up of today. The bios for the investment staff of Yale’s $42 billion endowment continue to include, as they did under Swenson, the position team members play, or have played, on the Ivy League endowment’s baseball team, the Stock Jocks.

The same pattern plays out on the investment manager side, especially among hedge funds, where the hiring preferences of a handful of successful firms (S.A.C. Capital Advisors, now Point72 Advisors, and Tiger Management being among the best known) came to dominate the makeup of the industry.

Pattern recognition

To be fair to asset management, this is what the industry was taught to do. Non-diverse teams, like Yale and Tiger Asset Management back in the day, were very successful. Yes, there have long been arguments that diversity can lead to better results. In practice, homogeneity won out. Allocators, in particular, tend to make decisions based on track record and resume. A certain type of background, a certain type of experience, and relevant networks have become a shorthand for that success. And, of course, the people who most fit that mold are white men from good schools.

It is true that in certain investment offices white women are well represented, although there are still very few women foundation or endowment CIOs or CEOs. Columbia University CEO Kim Lew remains the only woman of color leading a major university investment office.

The clubby world of endowment and alternative investing is now being confronted by a world that is demanding a far greater level of diversity and inclusion. And because these are (mostly) nice reasonable people – who want to be inclusive, do not consider themselves to be racist or sexist, and even see discrimination in this society – many do want to improve.

The problem, however, is that most organizations are unwilling to change their actual culture. And diversity without equity and inclusion, without respect and equality, is often little more than tokenism and lip service. This can lead to the absolute opposite from the intended consequences of greater inclusion, and undermine the benefits (as well as the moral imperative) of having diverse teams in the first place.

Which brings me back to what’s going on in cricket in the U.K.

More than a game

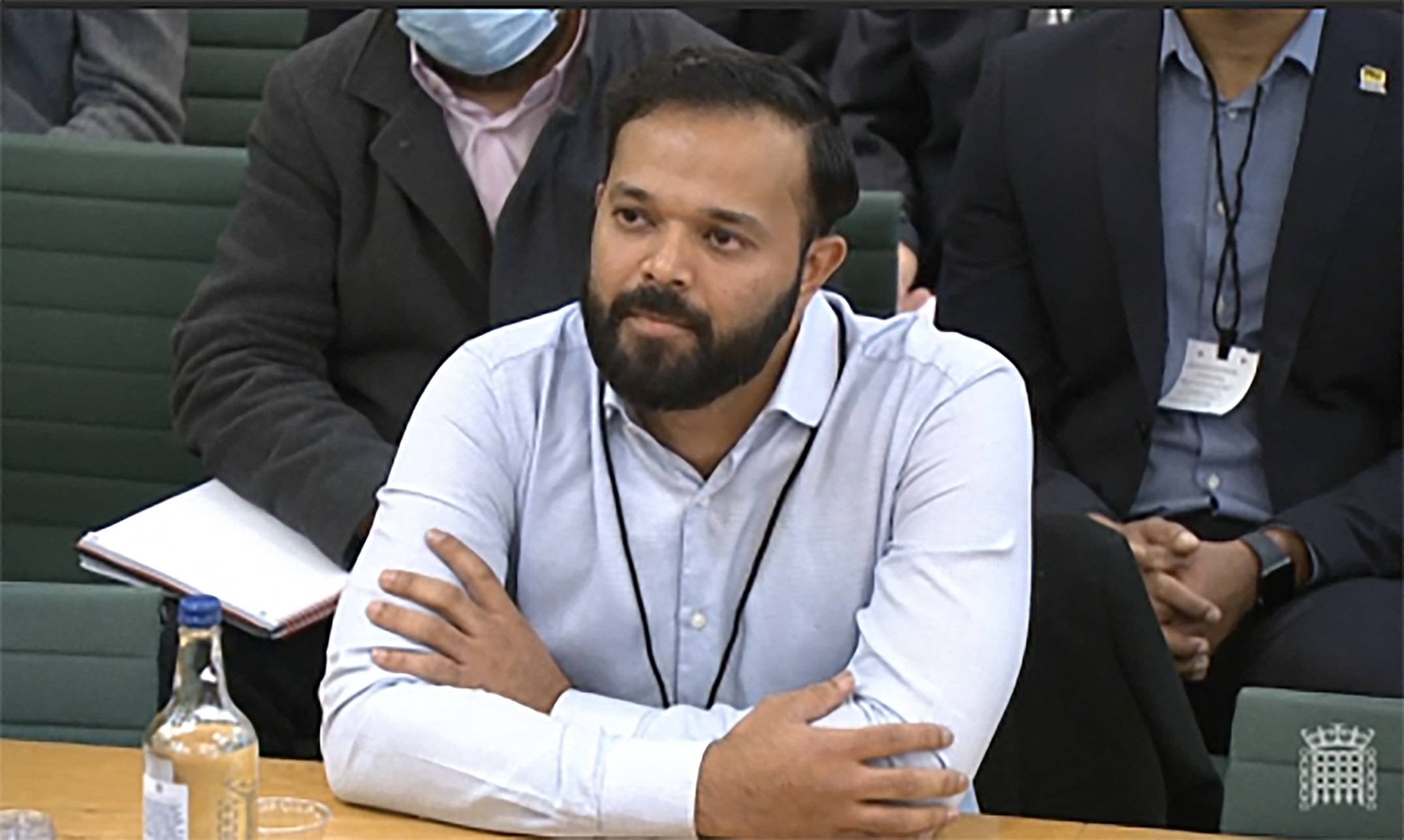

Last month, Azeem Rafiq, former captain of Yorkshire County Cricket Club, testified before a U.K. parliamentary hearing about the appalling racial and ethnic abuse he and other players of East Asian descent experienced at Yorkshire County.

Tears streaming down his face, Rafiq, who was born in Pakistan and at 12 moved with his family to the U.K., told MPs he believed he lost his career to racism and would not want his son “anywhere near” the game. He described instances of verbal racial harassment by key players and one instance where at age 15 he, a Muslim, was forced by other team members to drink alcohol.

What elevated Rafiq’s accusations to the level where they required a parliamentary hearing and numerous resignations was the manner in which Yorkshire County Cricket Club, one of the top cricket clubs in the country, and the England and Wales Cricket Board mishandled the situation.

Rafiq first went public in September of 2020 in a media interview in which he opened up about how he was “close to committing suicide” after his experience at Yorkshire.

The club, which had initially heralded Rafiq’s arrival as a triumph for its efforts to embrace diversity, ignored his accusations of racism, Rafiq said. Eventually, he said, “I was living my family’s dream as a professional cricketer, but inside I was dying. I was dreading going to work. I was in pain every day.”

“Look at the facts and figures. Look at a squad photograph. Look at the coaches. How many non-white faces do you see?” Rafiq asked ESPNcricinfo. “Despite the ethnic diversity of the cities in Yorkshire, despite the love for the game from Asian communities, how many people from those backgrounds are making it into the first team? It’s obvious to anyone who cares that there’s a problem. Do I think there is institutional racism? It’s at its peak in my opinion. It’s worse than it’s ever been.”

Rafiq says racism drove him out of the game. He lost his contract at Yorkshire not long after finding out during a one-day game that his son had been stillborn. The original interview where the cricketer unloaded was meant to be about his new venture – during COVID he and his family opened a Pakistani tea shop.

After the allegations from the former England Under 19’s captain, Yorkshire County Cricket Club, eventually, opened an investigation. The eventual report admitted the club had a problem with racism, but held no one accountable and was broadly seen as an, ahem, white wash.

Performance art

Azeem Rafiq’s story relates to asset management in at least two ways.

The first is just the sheer amount of talent that we leave on the table when we choose to allow, or participate in, discrimination. From all accounts as a cricket mad young man, Rafiq was among the top talents of his generation. He made his Yorkshire debut at 17, and did good cricketing things. Injury aside, there was no reason he could not have gone on to thrive. Yet he ended up on a downward trajectory that saw him crash and burn by age 28.

The same is true in asset management. Study after study shows the value of diversity to collective intelligence and positive investment outcomes. We know there are many, many talented women and BIPOC investment professionals. And yet, few get hired, certainly not into senior roles. Many drop out of a workforce that is not inclusive or accommodating to them. (Rafiq told ESPNcricinfo “as I stopped trying to fit in, I was an outsider. There were no coaches on the staff from a similar background who understood what it was like.”)

Members of the asset management community may not be tying their teetotalling colleagues to chairs and forcing red wine down their gullets. But we all know of investment offices that, even while promoting diversity, are not accommodating of differences and do not make sure everyone feels, and is, supported.

My second point: It’s not as if Yorkshire County Cricket Club and the England and Wales Cricket Board didn’t know they had a diversity problem. They touted Rafiq as (in effect) a diversity hire, even as his colleagues were abusing him and management was ignoring his complaints. The head of the cricket board was accompanied to the parliamentary hearing by the organization’s chief diversity and communications officer. They know, and they’ve been working on this for years.

And here is where I think the asset management industry should be worried. If they don’t truly tackle diversity, equity and inclusion… if they don’t make a sincere effort to achieve cultural change… if this is all just performative box-checking to appease stakeholders and political pressure… then there is a danger that rather than becoming more diverse, asset owners and investment managers actually become less inclusive, objectifying their female and BIPOC colleagues and fund managers as tokens of inclusion and not real people doing real jobs. Studies show diversity training actually leads to less diverse teams, because it builds hostility and resentment.

We are not doing enough.

Take the University of California. For the last couple of years, after being required to do so by the California state legislature, the Office of the Chief Investment Officer to the Regents of the University of California (where, in full disclosure, I used to work) has been reporting on its diversity efforts. Some are heralding the UC’s initiatives as groundbreaking.

Recently Chief Investment Officer Jagdeep Singh Bachher pledged to meet with 100 emerging (meaning women and minority-owned) investment managers. But if none of those meetings result in actual asset allocations then the CIO is just wasting the time, and hopes, of hard-working smaller investment firms which can ill afford to be somebody’s diversity prop.

The UC’s senior investment leadership has arguably become less diverse since Bachher took over in 2015 than it was under the previous, female, CIO. And the majority of the UC’s $168 billion portfolio (as of June 30) is managed by firms that have little diversity in their senior ranks.

The effort to make asset management more inclusive is not new. So-called emerging manager programs, designed to encorate investment in women and BIPOC owned investment firms, have been around in the public pension sector, and at some foundations, and even corporate pension plans, for two decades or more.

Yet, the report from the Financial Services committee makes clear how little overall progress has actually been made, including by firms that bring in millions of dollars in fees every year from public money, from pensions and public universities.

Last Thursday, Rep. Waters’s committee called to testify representatives from BlackRock and State Street Global Advisors, two of the country’s three largest investment managers. Like the UC, the $4 trillion State Street has, in recent years, made a big deal of its DEI initiatives. In 2017 the Boston-based investment manager won praise, and plenty of ink, for its “Fearless Girl” campaign, which featured a bronze figure of a young woman in front of Wall Street’s famous charging bull statue on Wall Street in New York as a way to press for gender diversity on corporate boards. Last year, State Street expanded the board campaign to racial diversity as well.

“We’ve made significant progress but as the committee’s report reveals, there remains much more to be done,” State Street’s Cyrus Taraporevala said in the virtual hearing. “Sustainable, meaningful advancements in diversity and inclusion require enduring changes to the way we all operate.

This is what we have in lieu of meaningful progress: a statue of a girl facing down a charging bull, and a marketing campaign in lieu of real change and commitment.

Imogen Rose-Smith is a contributing editor at ImpactAlpha. A longtime senior writer for Institutional Investor, she was most recently a fellow in the Office of the Chief Investment Officer of the University of California.

Catch up on all of Imogen’s Institutional Impact columns.