Carbon is a hot commodity.

The market for carbon removal – which spans soil carbon sequestration, reforestation and the enhancement of natural processes like ocean-based carbon absorption to technological solutions that capture carbon from the air and store it – is projected to be worth $1 trillion to $4 trillion between 2037 and 2050.

In addition to eliminating carbon from the atmosphere, carbon dioxide removal (known broadly as CDR) also provides co-benefits – that is benefits, expected or unexpected, that a project provides other than a net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Such co-benefits, from clean water to improved livelihoods, are beginning to be priced into carbon credits and offsets.

But the speculative boom of the carbon market is only a fraction of the value of nature. About half of global GDP – some $44 trillion – depends on nature, according to the World Economic Forum. Some argue that 100% of the economy is dependent on nature.

It’s time to flip the script and put nature at the center: carbon removal is actually a co-benefit of nature.

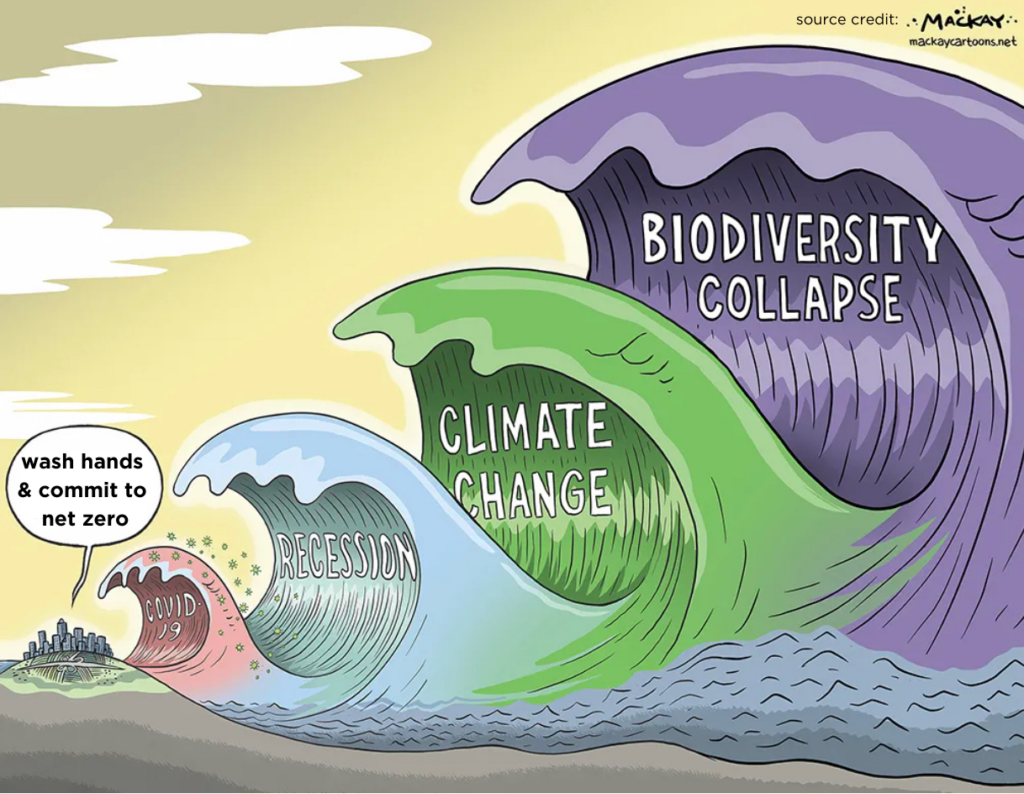

A growing body of research (see Ostrom, Costanza, de Groot, Paulson, Dasgupta, IPBES-IPCC, et al.) make similar points:

- The climate/carbon crisis is not separate, it is a symptom of a much greater problem, nature loss.

- Nature is a public good.

- Value nature. Or else.

BloombergNEF’s recent Biodiversity Finance Factbook articulates what’s at stake: About $1 trillion annually is needed in biodiversity funding, a gap of about $830 billion a year. But $1 trillion to protect biodiversity is cheaper than the cost of inaction, as the researchers point out.

A part of nature, not apart from nature

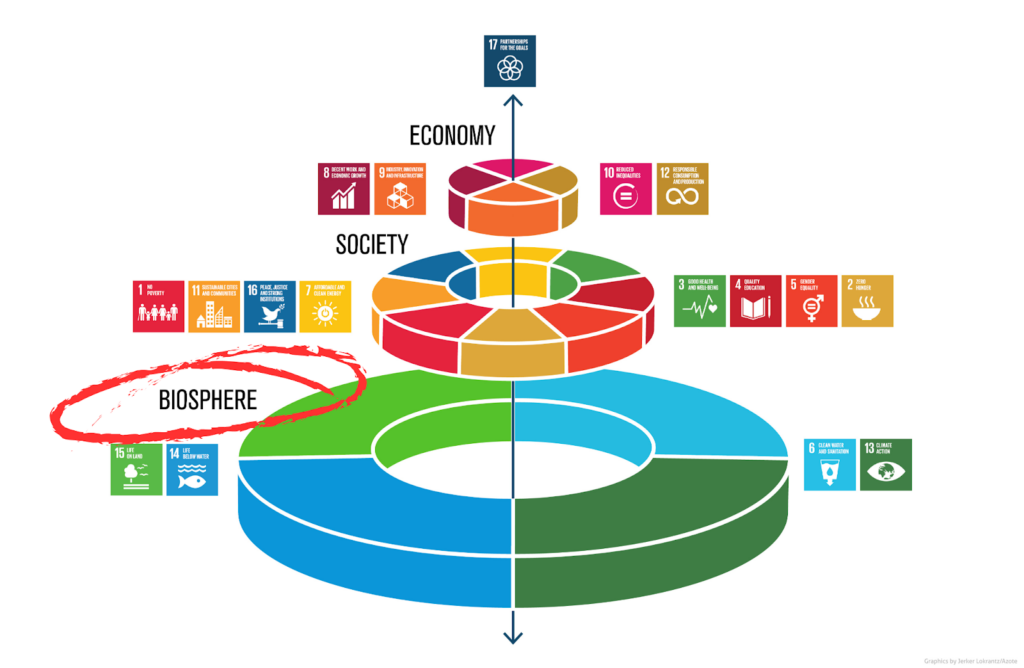

Humans are a part of nature and cannot exist without the numerous benefits it provides.

Besides the direct material benefits (food, shelter, nature-derived consumer goods) nature provides a multitude of indirect and protective benefits. They include erosion control, clean air, storm surge protection, wastewater filtration, pollination, nutrient cycling, habitat, soil, medicines and much, much more. Recreation, scenic views, and inspiration for art and culture are also part of what the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) calls “nature’s contributions to people,” or NCP.

The Biosphere underpins Society and the Economy

The problem is that we don’t currently account for most of these benefits. We treat them as free, but they could soon be at a cost that we cannot afford: biodiversity is shrinking faster than at any point in human history. There is a strong possibility that up to 50% of all species could be lost by 2050.

A deeper reason this epoch is called the Anthropocene is that the climate crisis is not about saving the planet – the planet will be just fine. It is about saving ourselves, or at least modern civilization as we know it.

Nothing is external

A commonly used and generally accepted accounting term is “deferred maintenance.” It refers to the practice of delaying necessary repairs or upgrades. If the repairs or maintenance are necessary, they shouldn’t be deferred. This is passing the buck.

In the same way, externalities are a fallacy. They are internal to someone, something, somewhere. Somebody has to or will pay the price.

CO2 emissions and nature loss are often considered externalities. What if we think of their solutions as public goods? Some are making the case that CDR facilities should be publicly owned, the way that water treatment and municipal solid waste plants are.

Too much carbon in the atmosphere, an impaired biosphere, or the loss of biodiversity affect us all. The question is, who pays for public goods and why.

Accounting for nature

Accounting for what is truly valuable may be the solution we need.

What is the worth of nature? What is the worth of carbon removal? Both are invaluable. But oftentimes invaluable means free, and people don’t value what they get for free.

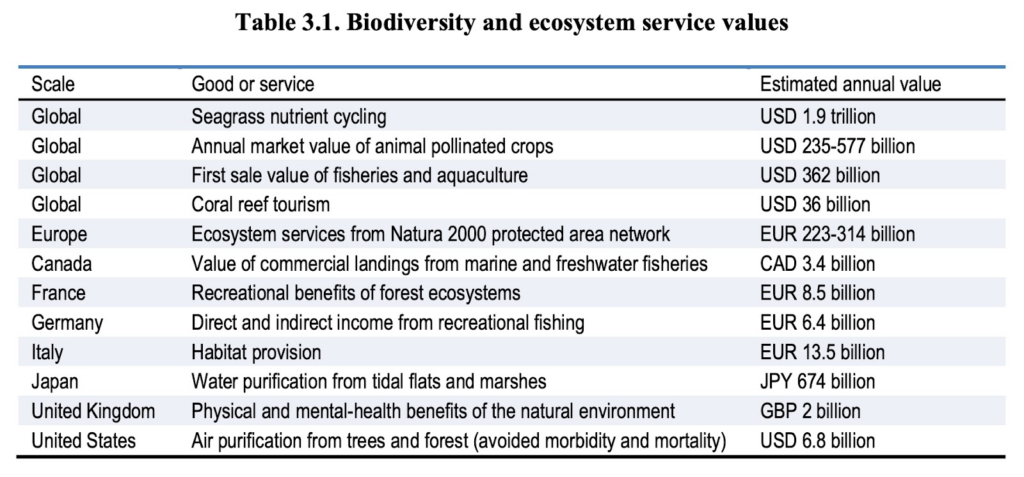

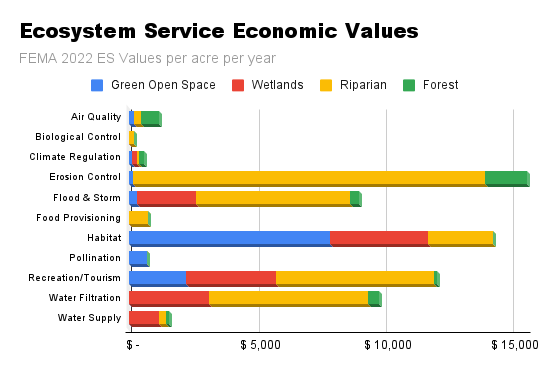

The field of ecological economics helps with this by establishing values for ecosystem services, or the benefits nature provides to people. For example, the air purification from trees represents $6.8 billion in avoided deaths each year in the U.S. alone.

If the most recent global value of ecosystem services, from 2014, were put into 2022 dollars, the value would be ~ $190 trillion annually. To put this in perspective, the projected $4 trillion carbon dioxide removal market that Exxon cites is 2% of that.

Every ecosystem type can now be valued. New datasets take into account spatial and temporal aspects as well. Recognizing that the natural environment is an important component of a community’s resilience strategy, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has adopted monetary values for ecosystem services. Its most recent Ecosystem Services Values update uses value per acre, per year. The Ecosystem Services Valuation Database, or ESVD, incorporates over 4,000 global studies across sixteen biomes and twenty-three Ecosystem Service Values using per hectare per year.

The per-ecosystem data further shows why carbon is a co-benefit of nature. Both FEMA and ESVD calculate climate regulation’s economic value at around 1% of the total ecosystem services value. (The data also shows that rivers, wetlands, and open space could easily dethrone forests and trees as the climate poster child. But I will save that for another day.)

An alternative framing is Core Benefits. Instead of looking at the follow-on effects of an activity, as co-benefits do, core benefits take a holistic systems based approach. At Basin, my regenerative finance venture, we are not after just CDR, or just clean water, or just clean air; we are seeking the sustainable well-being that is provided by a resilient biosphere and society.

Climate is both/and

Just as society needs to avoid and reduce emissions, we definitely are going to need all the technological carbon removal we can get. The development of direct air capture (DAC) and other carbon removal technologies, along with the broader decarbonization of the economy, are going to take time. In the meantime, we need to fund the restoration and conservation of ecosystems and carbon sinks as fast as possible.

A way to fund both nature-based solutions (NbS) and carbon removal is through the valuation of the benefits each provides.

Ecological and environmental economics are getting better and better every day. In March, the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures, or TNFD, released its fourth and final draft of the much anticipated nature disclosure framework for business and financial institutions of all sizes, across all sectors and jurisdictions. TNFD builds on the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and incorporates several commonly accepted environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting frameworks, including (at the risk of acronym overload) GRI, SASB, and SBTN.

Imagine how the values of climate regulation above could change if CDR was appropriately valued. The Social Cost of Carbon, a federal estimate of carbon’s costs to society, kind of does this, but is framed as a cost rather than the value of the benefits. As an example, what will be the per acre, per year value of direct air capture? Pretty high, I suspect. It could even be argued that in a world that continues to emit, CDR’s economic value is actually the sum value of all of society, the economy and nature, because without large scale CDR we are really screwed. So, I urge you to bring the science and research to establish and support these value of these core benefits.

Real wealth

Regardless of nomenclature, pigeonholing, and maximalism, at the end of the day we all want to feel safe, secure, and be happy. Historically the word “wealth” meant “well-being, health, happiness, prosperity and preservation.” Money and financial wealth was a byproduct, not the focus. Besides family, friends, and pets I don’t know of anything that provides incalculable benefits besides nature (which CDR will help restore and protect).

If you want to remove carbon, invest in nature. If you want clean water, invest in nature. Clean air, invest in nature. Risk reduction, invest in nature. Climate resilience, invest in nature.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Thomas Morgan (aka TMO) is the founder of Basin, which from day one was designed to make biodiversity and natural capital investable. To learn more about how Basin is creating a new real estate investment class to scale climate, nature, and carbon project development for climate resilience, connect with TMO on LinkedIn or Twitter.