ImpactAlpha, July 14 – It was an irresistible meme: A crash transition to organic farming tanked Sri Lanka’s agricultural sector and sent the country into an economic and political tailspin.

Except it’s not true. Scenes of protesters swimming in the presidential mansion’s pool, burning the prime minister’s residence—the imminent resignation of both leaders, members of a powerful and long-standing political dynasty—are the result of years of poor economic policymaking and corruption.

The fiasco that was the country’s organic policy was just one part of a complex series of mistakes, and says more about the country’s governance than it does about organic agriculture.

“We’ve known this was coming,” one former investment banker and impact investment officer told ImpactAlpha.

Bad policy

The writing was on the wall soon after Sri Lanka ended its 26-year-long civil war in 2009. The Indian Ocean island nation began borrowing heavily from multilateral banks and bilaterally from China, Japan and others to rebuild industry and infrastructure.

Not all of the capital was well appropriated: $1.4 billion was spent on a port in Hambantota, in southern Sri Lanka; an airport in the same city.

A large portion of Sri Lanka’s debt—more than $8 billion—was set to come due in 2022. Meanwhile, the country of 22 million already had one of the lowest tax rates in the region before President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who was elected in 2019, cut taxes further, slashing an important revenue stream.

“The state was living larger than it could afford,” the banker said.

Perfect storm

Sri Lanka is an import-dependent nation, particularly for fuel, food and medicine. It’s also import-dependent on revenues: from tourism and remittances—two sources of capital that all but disappeared when the pandemic hit.

The government resorted to printing money and using reserves to service Sri Lanka’s debt. Consumers started feeling the effects of inflation on daily essentials early in 2022. The currency was devalued. The war in Ukraine sent fuel prices soaring.

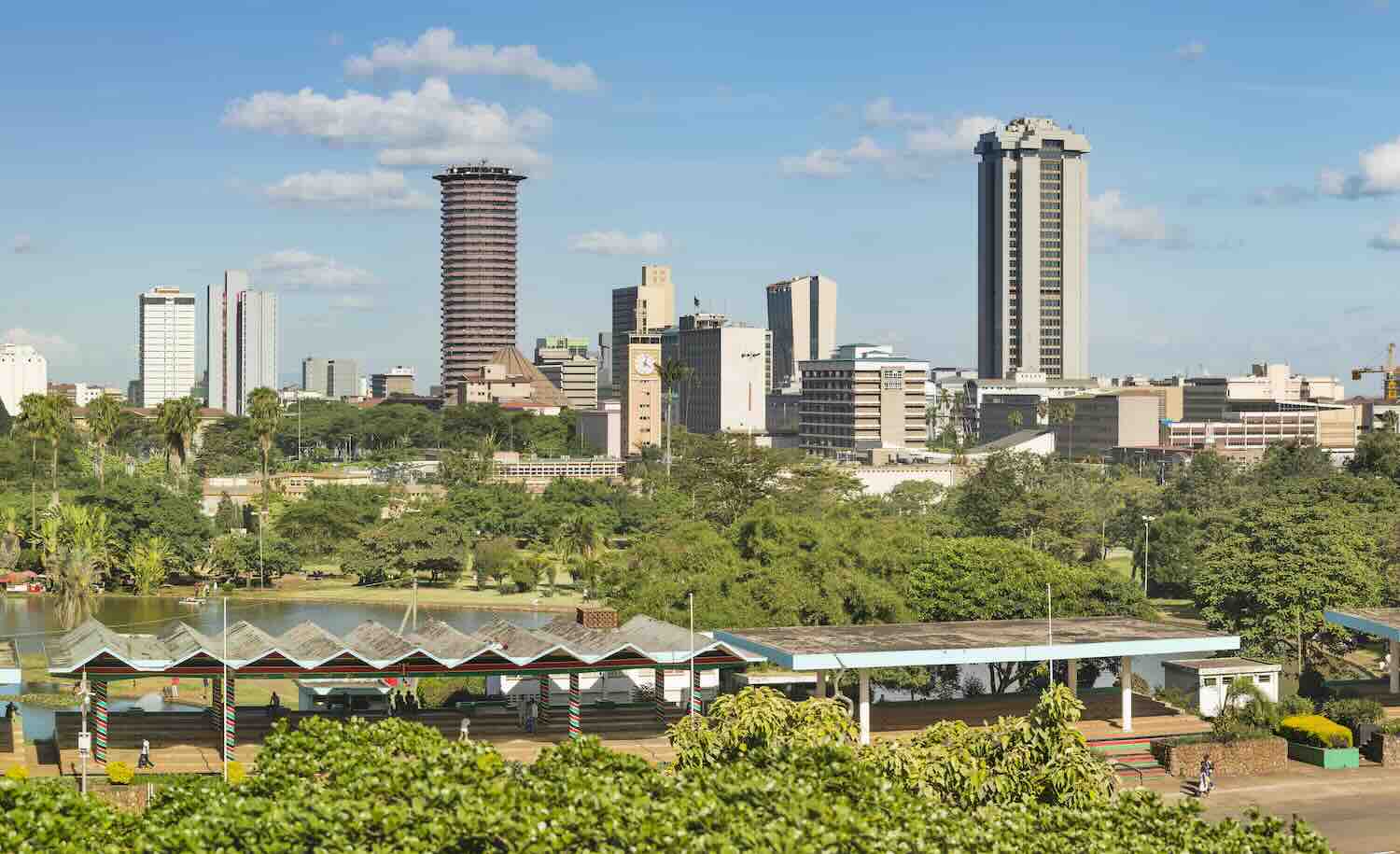

“Fuel shortages and long queues have severely disrupted daily life,” said IIX’s Jonathan Abeywickrema, who is based in Sri Lanka’s capital, Colombo.

Protests that have been happening for months have reached a peak. In the past, Sri Lanka’s working class and minorities have been the face of civil demonstrations, and their issues were for too long ignored, observed the banker. “Now everyone is protesting.”

Farming failure

President Rajapaksa promised to introduce all-organic agriculture in Sri Lanka, partly in response to community health issues that arose from agricultural runoffs that contaminated water supplies.

At a minimum, it takes several years for conventional farmland to be converted and certified organic. Soil nutrients have to be replenished. Farmers must be trained in using new crop varieties, inputs and farming techniques.

Last spring, Sri Lanka’s government imposed an overnight ban on synthetic fertilizers in what appeared to be a cost-saving move amid the country’s increasing financial hardship. (Other observers argue that it was simply a matter of poor policy execution.) Farmers were largely left to figure out how to grow rice, tea—a key export—bananas and other crops on nutrient-depleted land with no assistance. Naturally, crop yields plummeted.

Models to watch

Prospects for near-term relief—from inflation, from food and fuel prices—seem poor. “There are a lot of obvious solutions” for the longer-term, says Abeywickrema, “especially in the space of agriculture, clean energy and inclusive entrepreneurship.”

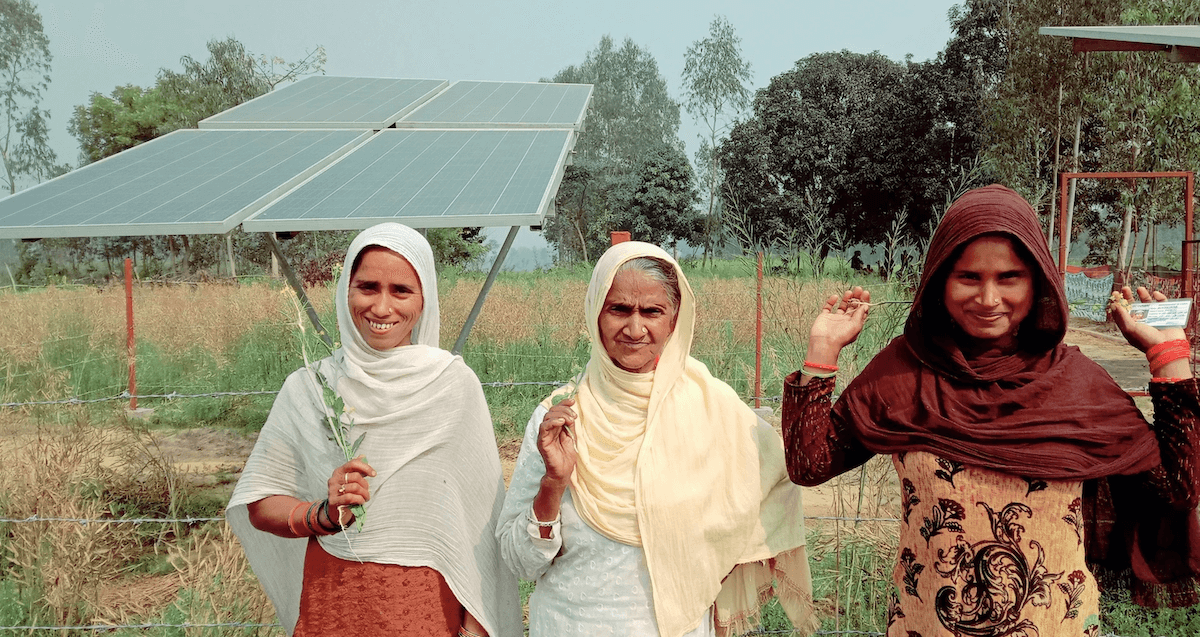

Adoption of solar power and electric vehicles would buffer Sri Lankans against fuel price volatility. Precision farming, organic farming (implemented with the proper training and support), and better linkages between farmers and buyers would reduce Sri Lanka’s dependence on food imports.

Early models are appearing in Sri Lanka’s nascent social enterprise scene. A number of small solar operators are encouraging Sri Lankans to adopt rooftop solar over traditional fuel sources. Social enterprise Dryzy, a dehydrated produce exporter, has for years been promoting organic farming while supporting livelihoods in rural communities. Euro Strong is developing building materials from upcycled waste, including plastic. D&D Creations employs women to make eco-friendly bags and other crafts, which the company sells to retailers.

Lanka impact

Early movers in Sri Lanka’s nascent impact ecosystem, such as Social Enterprise Lanka and Lanka Impact Investing Network, Sri Lanka’s first dedicated impact fund and advocacy group, are working to support emerging social entrepreneurs. Resources are very limited, says Abeywickrema, who worked with Lanka Impact Investing Network before joining IIX. What’s needed: attention from impact accelerators and investors to help these models grow, as well as a clearer investment pathway for impact investors outside of Sri Lanka.

The few impact investors in the country can’t cut checks small enough, he says. That includes IIX, which invested in Sejaya Micro Credit, a microfinance institution in Sri Lanka, via its second Women’s Livelihood Bond.

“Anyone looking at the country at the moment could cut Sri Lanka off the investment list because of the macroeconomic risk,” acknowledges Abeywickrema. “But there are solutions here in healthcare, energy and agriculture that can be self-sustaining, and are a hedge against whatever the government is doing.”