The World Bank Group’s and International Monetary Fund themed their recent meetings in Washington, DC, “The way forward: Building resilience and reshaping development.” Among the policy issues addressed: climate mitigation, supply chain resilience, food prices, sovereign debt and other fiscal challenges, the digital divide, human capital development.

Prioritizing health is essential to progress in all of these realms.

A nation’s health and economic wellbeing are inextricably tied together, as Covid-19 forcefully demonstrated. But while the pandemic exposed alarming weaknesses in global public health and healthcare, the swift response also signaled our capacity to shake off structural constraints, form effective partnerships, and broaden access to care and lifeline financial support when necessary.

Governments, the private sector, and international organizations should take that to heart as they consider domestic initiatives to create health system resilience, including the build out of the World Bank’s new Pandemic Fund and other next-generation health and fiscal policies.

Healthy populations

We recently co-chaired the “Dialogue on national fiscal policy and health,” which brought together a small group of former health ministers and finance ministers from around the world at the Aspen Institute. Our charge was to reach consensus on a set of broad principles that regional, national, and international entities could use as a shared framework for strategic planning, regardless of their individual governance structures, income levels, or health system infrastructure. The common thread among these disparate players is that health spending is a core investment in any nation’s future, not merely a tally of expenses.

That finding animates our conviction that responsibility for a nation’s health is shared by all government ministries and departments; it cannot reside in the health sector alone.

Open channels of communication between health and finance ministers are essential to accurately value the contributions that vigorous health systems and healthy populations make to the economy. The considerable two-way interactions between health and the education, environment, housing, and social security sectors require a budgeting approach to track those contributions and investments.

A broader lens recognizes the private sector as an intrinsic part of any health system, one best positioned to make equitable contributions when working relationships on level ground are established between health and finance. The public/private partnerships that were at the center of the Covid-19 response offer a model for alliances that can diminish fragmentation and elevate efficient resource allocation.

Fostering partnerships

A climate of transparency, accountability, and social cohesion is fundamental to building the trust necessary to drive these cross-sector partnerships. To sustain funding levels for health, governments need to know that their resources are being used properly and that their expenditures actually improve population-level and individual indicators.

In the private sector, the willingness and capacity to invest also depend on stable and consistent access to innovative financing mechanisms and opportunities to scale success.

All of that places a degree of responsibility on the health sector to establish the economic value of its work. A robust health information infrastructure is a core requirement for making that case. The capacity to collect and analyze data about disease burden, treatment outcomes, cost-effectiveness of care, and the distribution of clinical services is essential to sound stewardship of public, private, and philanthropic funds.

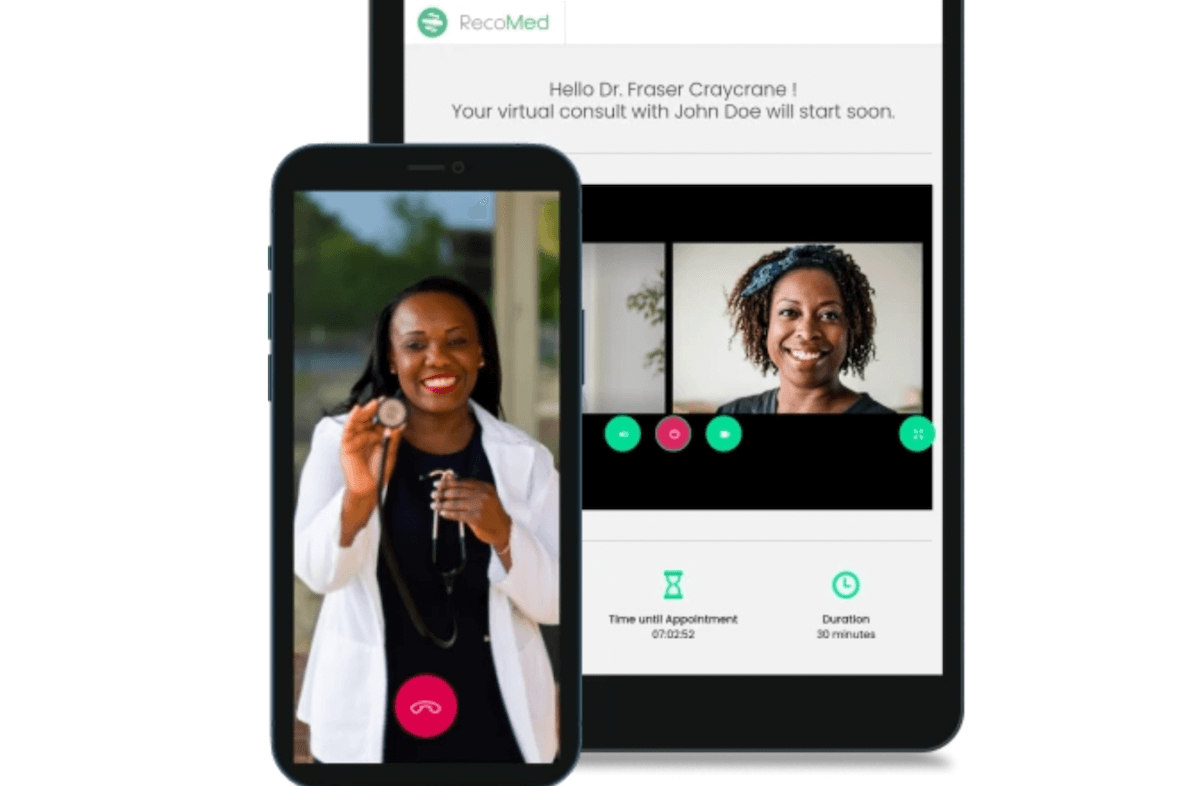

So, too, are investments in technology that bring medical services to underserved areas, capture early reports of disease outbreaks, improve the equity of the supply chain, build transparency into procurement processes, and increase workforce productivity, all while serving as an engine for economic growth.

Once health and finance ministries align around mutual benefits, they can work together to determine budget priorities and define the role of public and private stakeholders. The equity imperative must be the pillar of their negotiations, reflecting the core belief that all lives have equal value and that better health and global health security depend on the fair allocation of public goods.

Given the role of social determinants, health-promoting activities that go beyond clinical services, from improved rural sanitation, to rejuvenated food systems, to better housing and schools, are key. Although measurable returns may not accrue for years, the potential for long-term benefits should be factored into budget equations, where possible, to counterbalance decisions that rest on short-term political considerations. Regardless of the tension between immediate demands and bold new approaches, efficiency and sustainability are watchwords to stretch available resources.

So, too, is a commitment to well-funded, readily accessible primary care and trained community health workers. Covid underscored those priorities as the countries most able to cope with the pandemic already had resilient primary healthcare systems in place. An integrated, community-based care infrastructure that emphasizes prevention and service coordination can lessen the burdens of both infectious and noncommunicable diseases in countries at every income level.

Effective collaboration

While much of this work falls within the purview of national governments, our existing global financial and health institutions also need more effective mechanisms to address ongoing and emergent challenges together. The vacuum of leadership apparent during Covid revealed that no single entity had the authority to guide a coordinated international response. The disease-specific funding patterns of many aid organizations also limit the attention they can pay to systems-focused investments.

We don’t believe it is necessary to birth a new organization but instead call on existing ones to strengthen partnerships, develop more nimble financial instruments, and bolster core health infrastructure. Considering the demands of effective public health within that framework provides an additional incentive for resisting fragmentation, a trend that is currently dominating international relations.

The inseparable goals of strengthening the economy and generating better health for all are increasingly urgent. As nations grapple with ever more complex challenges and finance ministers consider spending choices to advance social welfare, the health sector needs to position collaboration as a win:win for the people, the government, and the planet.

John Lipsky was former first deputy managing director of the International Monetary Fund. He currently chairs the National Bureau of Economic Research, co-chairs the Aspen Institute’s Program on the World Economy, and is a senior fellow of the Foreign Policy Institute of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.

Donna Shalala served as secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services in the Clinton Administration. She was past president of the University of Miami and is currently trustee professor of political science and health policy at that school, as well as a member of the Council on Foreign Relations.