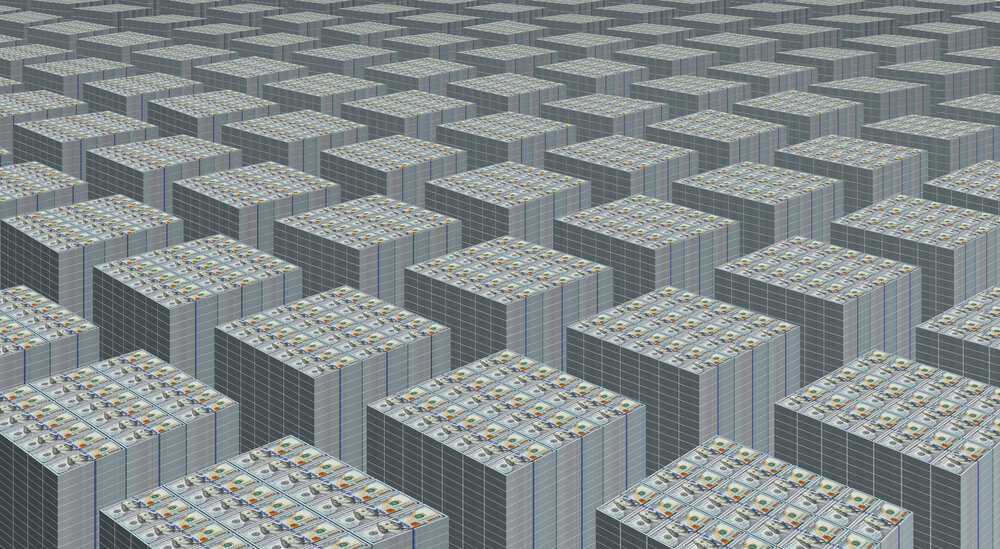

ImpactAlpha, Oct. 29 – As the COP26 global climate summit kicks off this weekend, much of the focus will be on the massive gap between what’s been promised and what is needed to avert climate catastrophe. The $100 billion a year needed by developing countries. The trillions needed to decarbonize the global economy by 2050. A pair of critical U.S. climate bills that hang in the balance.

“It’s really easy to get overwhelmed by the magnitude of the challenge that we’re facing, especially when we look at the trillions that are required here,” said John Balbach of the MacArthur Foundation. A more productive approach, he says, is focusing on the “bottom-up” solutions being built by innovative leaders to address clear and tangible climate capital gaps. “That’s ultimately how we mobilize real capital.”

The key: deploying catalytic capital – patient, flexible, concessionary funding – to de-risk critical climate solutions and unlock additional capital.

ImpactAlpha’s Call No. 33 gathered some of the bottom-up innovators who are bridging capital gaps, propelling climate solutions and accelerating the transition to a net zero economy.

Early stage

For Prime Coalition, that means investing at the earliest stages in startups with the potential to eliminate carbon at scale. The Cambridge, Mass.-based nonprofit takes in mostly program-related investments from its funding partners and invests in startups that are considered too early or risky for commercial investors.

“We are an unapologetically impact-first fund,” says Prime’s Amy Duffour.

The $52 million Prime Impact Fund has invested in 19 startups. A key consideration: creating impact that would not necessarily have been achieved without Prime’s investment, what’s known as “additionality.”

Such early interventions can help get startups through the challenging period of proving out their idea and building a product or service. “We believe that we can de-risk these early stage climate tech companies for more conventional downstream investors,” said Duffour.

When Prime led a seed round for Lilac Solutions in 2018, for example, the startup was still building its team and had no commercial traction. But Prime saw great potential in Lilac’s environmentally friendly approach to extracting lithium, an essential element in electric vehicle batteries. Prime worked closely with Lilac for more than a year. The startup went on to raise $20 million in a round led by Breakthrough Energy Ventures, and more recently, another $150 million round led by Lower Carbon Capital and T. Rowe Price.

The hand-off to Breakthrough Energy Ventures, the venture arm of Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy, is not a one-off. BEV has invested in several Prime Coalition portfolio companies still in their early stages.

As those young companies develop, they fall prey to another potential trap: funding capital-intensive demonstration plants to prove and commercialize their solutions. A new unit of Breakthrough Energy, called Breakthrough Energy Catalyst, was launched earlier this year to address that particular gap.

Breakthrough Energy Catalyst has raised about $1.5 billion from BlackRock Foundation, Microsoft, General Motors, American Airlines and ArcelorMittal and other corporate funders. It’s also partnering with European, U.S. and U.K. governments to build demonstration plants for technologies they are supporting.

“Transitions are made when things are done either better or cheaper,” said Breakthrough Energy’s Jonah Goldman.

Corporate capital

Catalytic capital is needed to help build plants for critical climate technologies such as low-carbon aviation fuel, long-duration storage or green hydrogen that are still far more expensive than the fossil fuel-based products they hope to replace.

Take green jet fuel. “There is a lot of exuberance when it comes to sustainable aviation fuel,” said Goldman. Airlines, green fuel producers and airports are all making commitments, while regulators are signaling they want green fuel on the agenda. “It’s perfectly safe. They figured out how to do it. All of those pieces of the puzzle have come together,” he said. One missing piece, he says, is “how do you finance something that still is at this point 2x what the alternative is?”

The Catalyst mode combines blended capital up front to defray the costs of building a plant or project with corporate offtakes – commitments to purchase the product or service once it is finished – on the back end.

What’s more, Catalyst’s corporate partners agree to pay a premium for the green alternatives. The motivations vary from gaining technical insights and first mover advantage to getting credit toward climate goals – or simply to do the right thing, says Goldman.

ImpactAlpha’s David Bank noted the “arrival of corporate capital” as not just an investor but a key buyer. “Much of climate capital actually is going to be coming from corporates in their operations and supply chain,” he said.

Indeed, corporations play a key role in a new pay-for-performance initiative to protect forests and sequester carbon.

The LEAF Coalition, or Lowering Emissions by Accelerating Forest Finance, was launched at Earth Day at the Biden climate summit with support from the governments of the U.S., Norway and UK.

It’s aim is to “mobilize $1 billion dollars from governments and corporations to demonstrate significant demand for conserving and protecting tropical forests” at a jurisdictional, or governmental, level, explains Heather McGeory of Emergent, which is brokering a market between buyers of carbon credits and forest communities.

Companies in the coalition, including Delta Airlines, GlaxoSmithKline, Nestlé, Bayer, and Amazon, commit to buying a minimum of 1 million tons of sequestered carbon at a floor price of $10 a ton. These “real contracts between sovereign governments and corporations” provide assurance to countries that they’ll be paid for their conservation efforts.

The model will help fill a yawning gap for climate adaptation in developing markets. “Climate smart agriculture, conservation, creating revenue lines around things like coastal preservation or mangrove preservation, all of these things are not easy to finance with private sector money,” said McGeory.

“We are in an emergency situation on this particular problem set,” she added. “And if we’re going to use blended finance to try to address it, we’re going to have to speed up by several orders of magnitude.”

Adds MacArthur Foundation’s Balbach: “We have to recognize that we’re building a foundation of long-term solutions for the future, all of which are about compressing the time period for the energy transition.”