ImpactAlpha, Oct. 20 – Climate finance is on a roll. Climate finance is stuck. Both statements are true.

Investors have poured record sums into climate funds and startups in 2021: $40 billion into the former and $16 billion into the latter, according to estimates. That doesn’t include project financing for sustainable infrastructure such as electric vehicle charging, waste-to-energy plants or indoor farms.

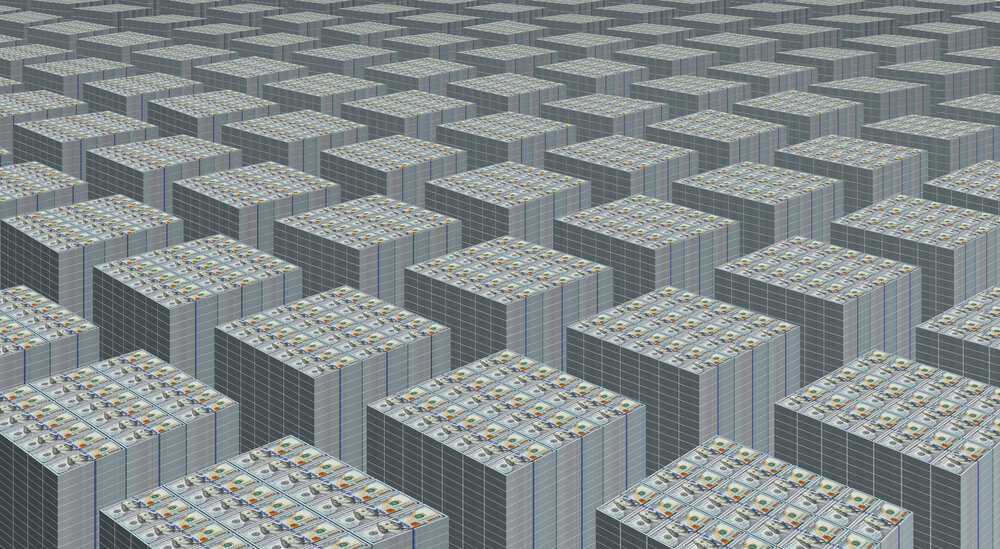

Yet significant gaps remain in key geographies, sectors and stages. And climate finance writ large is still measured in the billions, not the trillions required to avert climate catastrophe.

Needed: Catalytic funding models to bridge the gaps. In the toolkit: blended capital, guaranteed offtake agreements and targeted project financing.

>>>Go deeper: Connect with Agents of Impact using catalytic capital to crowd in financing to scale up climate solutions on “Call No. 33: Catalytic climate capital,” Tuesday, Oct. 26. RSPV today.

Funding flows for climate mitigation and adaptation have plateaued over the past four years, according to the Climate Policy Initiative. Global climate spending by public and private actors totaled $640 billion in 2020, up less than 3% from 2019’s $623 billion, according to CPI’s latest figures. That’s barely higher than CPI’s 2017 tally of $612 billion (financing actually dropped to $546 billion in 2018).

With continued falling costs for solar and wind power and a raft of big fund raises, there are indications that climate financing may top $1 trillion this year. But experts say three or four times that amount is needed each year to keep the goals of the Paris climate agreement in range.

“Climate investment should ideally count in the trillions, whereas fossil fuel investments should virtually stop this decade,” said CPI’s Barbara Buchner. “This decade will make or break the transition to a sustainable natural world.”

Early-stage innovation

The funding levels to underwrite the shift to a low-carbon economy are underwhelming, if not downright head-scratching for what’s been alternately called an existential threat and the investment opportunity of a lifetime.

For years, venture capital showered money on software companies and apps with low capital costs. Many climate startups pursuing solutions from batteries to carbon capture to waste-to-fuel systems require significantly more capital to prove out and build their products.

Prime Coalition launched in 2014 to fill an “idea-to-impact gap” for capital-intensive startups that have the potential to eliminate at least half a gigaton-scale CO2 emissions by 2050.

The Cambridge, Mass. nonprofit taps philanthropic capital to make equity investments that provide patient capital and additive impact.

In 2014, that was a fairly simple determination of whether or not a promising startup would be able to raise capital without Prime Coalition coming in. Usually the answer was no.

Now that venture investors are hot on climate tech, that additionality assessment has become more nuanced, says Prime’s Sarah Kearney. Now it might look at whether Prime can make a difference in helping a company achieve its optimal climate impact, or provide an alternative to overly competitive or usurious terms, or enable a company to prioritize a product application that finance-first investors might discourage.

“It’s a much different world than we were living in when we founded Prime in 2013,” Prime Sarah Kearney told ImpactAlpha. Prime’s $52 million impact fund “would never do a hot deal” that investors are scrambling to get into, “because of our catalytic mandate,” says Kearney.

Commercial scale

If Prime is filling a gap for early-stage climate tech, others are looking to intervene at another critical stage for climate innovators: the first deployment of their product or first project buildout.

Breakthrough Energy Catalyst, the latest initiative of Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy, has raised more than $1 billion for a “nontraditional traditional blended finance mechanism” to accelerate commercialization and declining cost curves for key climate solutions, including clean jet fuel, long-duration storage, green hydrogen and direct air capture technologies.

“People talk about the solar cost journey as a 10-year incredible decline. They forget about the 40 years before that,” Breakthrough Energy’s Jonah Goldman told ImpactAlpha.

BlackRock’s philanthropic arm donated $500 million and Microsoft $100 million. Corporations including General Motors, American Airlines and ArcelorMittal stepped up with equity capital as well as advance purchase, or offtake, agreements.

Breakthrough Catalyst is also partnering with European and U.S. governments to help build demonstration plants for technologies they are supporting. On Tuesday, it announced a similar deal to match the U.K. government’s £200 million investment in cutting-edge climate technologies with private sector capital over ten years.

Solar pioneer Jigar Shah, who now heads the Department of Energy’s loan programs office, points to a $50 to $100 billion shortfall for project equity this decade. The loan office provided early capital for Tesla as well as biofuel, solar and wind companies. The gap comes when they are looking to build their second, third and fourth plants, he said. “A lot of the private sector players have gone, from an equity standpoint,” he told Bloomberg News.

Scott Jacobs of Generate, Shah’s former firm, pegs the project equity gap at $50 to $100 billion a year.

Guaranteed offtakes

Offtake arrangements like those deployed by Breakthrough Energy Catalyst de-risk projects by guaranteeing a customer for the product or service, be it captured carbon and sustainable biofuel. They are emerging as a critical part of the catalytic capital equation.

In the Amazon, forest products hold great potential to generate sustainable livelihoods but local value chains are typically under-resourced. Sao Paulo-based asset manager Mauá Capital and personal care products B Corp. Natura have developed a blended finance mechanism to help strengthen local supply chains and forest communities. The Amazonia Sustainable Supply Chains Mechanism, as it is called, aims to protect 3 million hectares of forests and avoid a potential 1.4 billion tons of CO2 emissions while supporting local cooperatives and small producers.

Natura’s role as an offtaker is key to the model, which was selected for the latest Global Innovation Lab for Climate Finance’s latest cohort. “In order to build a more resilient system, you bring an offtaker,” Mauá Capital’s Carolina da Costa told ImpactAlpha. “That is going to help us to de-risk the operation.”

The model centers on a receivables fund that pays forest farmers upfront for their products. Natura repays the fund for the future products and is also a subordinate investor in it. An adjacent “enabling conditions facility” provides technical assistance to suppliers and invests in education, healthcare and infrastructure in local communities.

Da Costa expects to bring in additional offtakers, such as food or pharmaceutical companies, that share the forest supply chain. “Because they know the value chain so well, risk for them is really diminished,” says da Costa.

Catalyzing climate capital

Private equity and venture funds get much of the attention, but account for just a tiny slice of climate spending. The largest chunks come from public sector institutions such as development finance institutions as well as private sector banks, and corporate and consumer spending.

Development finance institutions climate funding averaged $219 billion a year in 2019 and 2020, while governments kicked in another $38 billion, according to CPI.

Public sector funding, in particular, could be more effective in mobilizing the kind of large scale capital flows needed to accelerate the transition to a low carbon-economy. The need is most acute in emerging markets, which have contributed little to historic greenhouse gas accumulations yet bear the brunt of climate change – and need help in investing in mitigation and adaptation strategies.

BlackRock’s Larry Fink, in an essay in the New York Times, is calling for an overhaul of multilateral development banks, agencies and climate funds so that they absorb some of the risks that keep private sector players from investing in emerging markets.

Low-carbon investment in developing countries total roughly $150 billion a year. That will have to increase by six-fold. “An essential part of raising the scale of capital necessary to transition emerging market economies to net zero will be using public finance to raise more private capital,“ he wrote.