ImpactAlpha, March 18 – The world’s largest carbon emitter reduced emissions by an estimated 25% last month. This month, the world’s second-biggest greenhouse gas emitter may also make dramatic reductions.

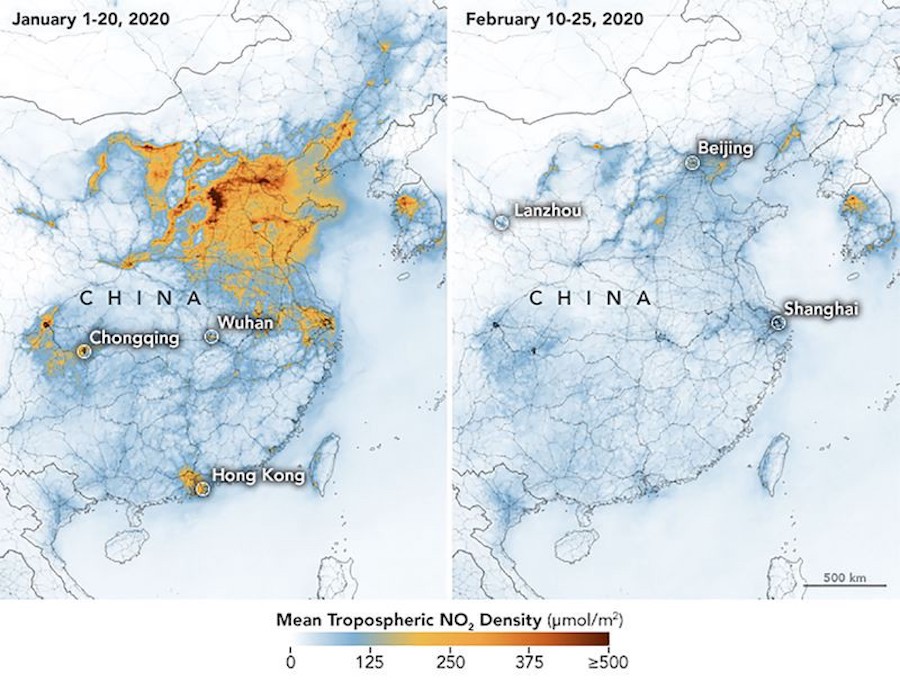

Satellite images from last month showed clear skies over chronically smoggy China as the country put activities on hold to contain the coronavirus. As many regions of the U.S. shut down workplaces, schools, events and air travel, carbon dioxide emissions are expected to fall sharply.

The world has just achieved what few thought was possible even a few months ago: distributed and concerted global action to make the kind of deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions that are necessary to forestall the most cataclysmic effects of climate change.

“The virus can be seen as the straw that broke the back of an unsustainable sector,” Carbon Tracker’s Kingsmill Bond told ImpactAlpha.

Can flattening the curve also bend the arc of carbon emissions? Even a modest downturn in demand triggered a crash in oil prices that will strand billions of dollars in fossil fuel assets. A good place to start would be reversing the trend toward ever-greater financing of the fossil-fuel economy that needs to shrink.

Is oil’s freefall the tipping point in the transition to a low-carbon economy?

An updated “Banking on Climate Change” report from Rainforest Action Network and other nonprofits, says fossil financing will hit $1 trillion per year by 2030 under banking business-as-usual. Funding of fossil fuels from the 35 largest banks has grown each year since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in late 2015, totaling $2.7 trillion, according to the report.

Leaders and laggards

JPMorgan Chase remains the “world’s worst banker of climate chaos,” according to the report. The No. 1 funder of fossil-fuels has put a total of more than $270 billion into such projects and companies since 2015. Banks scoring the least worst on climate financing: Crédit Agricole, RBS, and UniCredit. Goldman Sachs ranked 12th, the best score for any non-European bank.

One to watch: Royal Bank of Scotland, which last month committed to halve the climate impact of its financing activity by 2030 and end financing for major oil and gas companies unless they put in place credible transition plans.

Global action. The question now is how to institutionalize the reductions and make them the new normal even when the emergency eases. Renewable energy supply is on an exponential growth curve that is unlikely to be reversed. “Governments need to step up to the plate and stop people from getting addicted to cheap oil, and thereby starting the whole cycle again,” Carbon Tracker’s Mark Campanale told ImpactAlpha.

Potential measures include: a carbon tax to keep prices at the gas pump level even as crude prices fall; an end to carbon subsidies, which remain double those of renewable energy; and, certainly, to reject any “shaleout,” or aid package for oil producers that are flailing in the global shakeout.

Climate Finance 2020: Leaders and laggards in the race to net-zero

Pledges, shmedges

Responding to growing investor and public pressure, banks have scrambled in recent months to make public pledges to curtail fossil fuel funding. In December, Goldman Sachs dropped future financing for oil exploration in the Arctic; JPMorgan followed in February. More than 100 banks have signed the Principles for Responsible Banking and the new Equator Principles.

“These laudable pledges make little difference,” says Johan Frijns of BankTrack; bank financing for the fossil fuel industry is “continuing to lead us to the climate abyss.” He and other activists call for an immediate end to funding for all new fossil fuel projects, as well as a rapid phase out of existing fossil finance. “This should be the Global Glasgow Goal for all banks,” said Frijns, referring to the upcoming global climate conference in November, where countries are expected to submit ambitious new plans.

Fine print

Among the spate of recently announced fossil fuel restrictions, many ban direct project financing for, say, coal or Arctic drilling. That conveniently obscures the general corporate funding to fossil fuel companies that banks provide, which drives a significant amount of fossil fuel development.

For example, more than 20 banks restrict Arctic oil and gas finance, notes the Banking on Climate Change report. But most ban project financing; just five limit corporate funding for the oil and gas companies that have the most Arctic reserves under production.

Similarly, many banks’ coal policies limit funding to companies who get a large share of their revenues from coal. That fails to address the many diversified, non-traditional coal companies that are expanding coal production.

Everybody in

Public sector funders, insurance companies and asset owners and managers are increasingly stepping up. One example: The European Investment Bank, the world’s largest multilateral development funder, announced in November it would cease funding fossil fuel projects after 2022.

“Debanking, deinsurance and divestment are now operating together in synergy,” write the Banking on Climate Change authors.