Contemporary efforts to grapple with the climate crisis almost all come with mid-twentieth century branding: a ‘Green New Deal,’ a ‘climate moonshot,’ a ‘Green Marshall Plan,’ a ‘World War Two-style mobilisation.’

Is this obsession with rhetoric that harks back to mid-twentieth century challenges leading us astray?

The truth is that the big challenge we face today – fully decarbonizing the global economy in less than 30 years – is not very much like recovering from a depression, fighting a war or building a rocket that can fly to the moon and back.

A better analogy might be the battle to tame inflation in the late 1970s and 1980s. Like climate change today, inflation in the 1970s was spiraling out of control. In both cases, the cause was – or is – misalignment between expectations and reality.

In the 1970s, as growth slowed but all sections of society continued to expect living standards to rise as fast as they had done in previous decades, wage and profit expectations became disconnected from economic realities.

Today, wage and profit expectations have become disconnected from ecological realities.

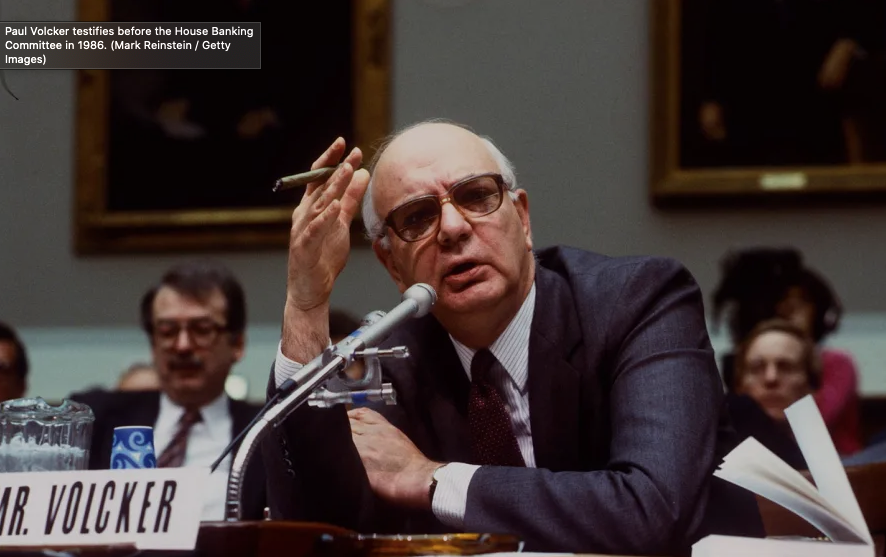

By 1979, governments and central bankers on both sides of the Atlantic had vacillated so much on how to handle inflation that they had little credibility left. The inflationary spiral became self-perpetuating because nobody expected monetary policymakers to do much about it. Then came the ‘Volcker Shock’.

Paul Volcker, who was appointed chair of the Federal Reserve in 1979, decided that the only way to shift expectations of Fed policy was to shock the market by raising interest rates dramatically and for a sustained period of time. This policy choice came at a heavy cost, inducing a recession in the US and a debt crisis in Latin America. But, judged in narrow terms, it was a success: inflation came down and stayed down. Volcker had successfully changed financial markets’ expectations about how the Fed would respond to rising inflation in the future.

Climate policy today – like monetary policy in the 1970s – suffers from a chronic lack of credibility. After years of empty rhetoric, here-today-gone-tomorrow policies like the U.K.’s Green Homes Grant, and the electoral success of climate skeptics in the U.S. and elsewhere, markets have little confidence in the robustness or predictability of future climate policies. Without that confidence, businesses and investors will not adjust – indeed, are not adjusting – capital allocation and business models in line with what’s needed to limit global warming to well below 2°C.

What are the lessons to be learned from post-1979 monetary policy that can help us tackle the climate crisis?

The first lesson is that politicians need to be honest with voters about the pain that halting global warming will involve. When Margaret Thatcher’s government implemented its own version of the Volcker Shock, she did not pretend it would be painless.

“We are paying the price for years and years of make-believe,” she told viewers in March 1980. “I’m afraid some things will get worse before they get better. After almost any major operation you feel worse before you convalesce. But you don’t refuse the operation when you know that without it you won’t survive.”

She could just as well have been talking about what it will take to break our economy’s fossil fuel addiction today.

The second lesson is about institutional design. Monetary policy’s credibility is underpinned by the norm of central bank independence and the rigorous pursuit of inflation targets. The equivalent for climate policy might be the creation of independent ‘Carbon Councils’, as advocated by former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney. Like central banks, Carbon Councils would receive their mandate from governments, which would set targets for reducing emissions on a particular trajectory – as the U.K. already does – and then delegate responsibility for achieving those targets to technocrats. And just as central banks coordinate with one another through global institutions like the Financial Stability Board, national Carbon Councils might coordinate with one another via a global Climate Stability Board.

There is an irony about the timing of this argument: today, for the first time in 40 years, inflation is on the rise and it is unclear whether central banks will have the resolve and credibility to tame it. Even so, in historical terms, 40 years is a pretty good run. More importantly, 40 years is more than we have to deal with the climate crisis.

Given that we must fully decarbonise the global economy by mid-century, the thought that the effects of a ‘Volcker Shock’ for climate might wear off by the 2060s seems like the least of our worries.

Richard Roberts is inquiry lead at Volans, a think tank and advisory firm focused on sustainability, innovation and market transformation.