In the state of Michoacan in western Mexico, indigenous communities have secured Forest Stewardship Council certification for their sustainably managed biodiverse temperate forests.

Their community-managed forests in Ejido Otzumatlan and Rio de Parras overlap with Cerro Garnica National Park, offering refuge to monarch butterflies, jaguars and other endangered species while also producing water for the region. Since the income from sustainably-sourced timber is not sufficient to support their livelihoods or sustainable land management, a forest carbon project developer convinced the groups to create carbon credits under the Climate Action Reserve standard.

Carbon credits, the reasoning went, would generate additional revenue to reward them for their excellent land and forest stewardship while affording additional resources to maintain and care for their forests.

A brisk market has grown for carbon credits, which enable polluting corporations to purchase credits representing a ton of CO2 avoided, removed or captured to offset their hard-to-abate emissions. The experience in Michoacan underscores both the promise and peril of carbon offsets.

After creating verified emission reductions in the form of “Carbon Reduction Tons,” international buyers offered less than $10 per ton of carbon. That’s barely enough to cover the cost of creating and verifying the carbon credits.

The meager economics have led these communities to consider abandoning their efforts to offer carbon credits altogether. At the same time, carbon credit buyers have pulled back after a series of exposes suggesting the nature-based carbon sequestering projects did not live up to their promises.

A scramble is on to fix the voluntary carbon markets before a promising avenue of funding for indigenous land stewards, biodiversity protection and carbon sequestration is closed off. Despite the controversies, nature-based strategies remain the most attractive and vital part of any robust portfolio of carbon offsets, offering the most expedient, least expensive results with the lowest risks to respond to our climate crisis meaningfully. Deforestation and the changes in land use account for about 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

From the US State Department to the Voluntary Carbon Markets Initiative, efforts are underway to create more stringent standards and guardrails to avoid greenwashing. The biggest push for quality is coming from a perhaps unlikely source: Big Tech titans have joined a select group of global corporations making significant efforts to reduce their carbon footprints and invest in carbon offset projects.

The new demand promises to raise global prices for high-quality carbon-emission reductions that also provide co-benefits for local communities and ecosystems. A price of $25 would make a big difference, experts say.

It is clear to these companies that emission reductions across their operations must be underway in order for carbon offsets to offer true value and not result in accusations of greenwashing. As carbon standards improve and regulated carbon markets mature, carbon removal becomes more scalable.

Big Tech’s role

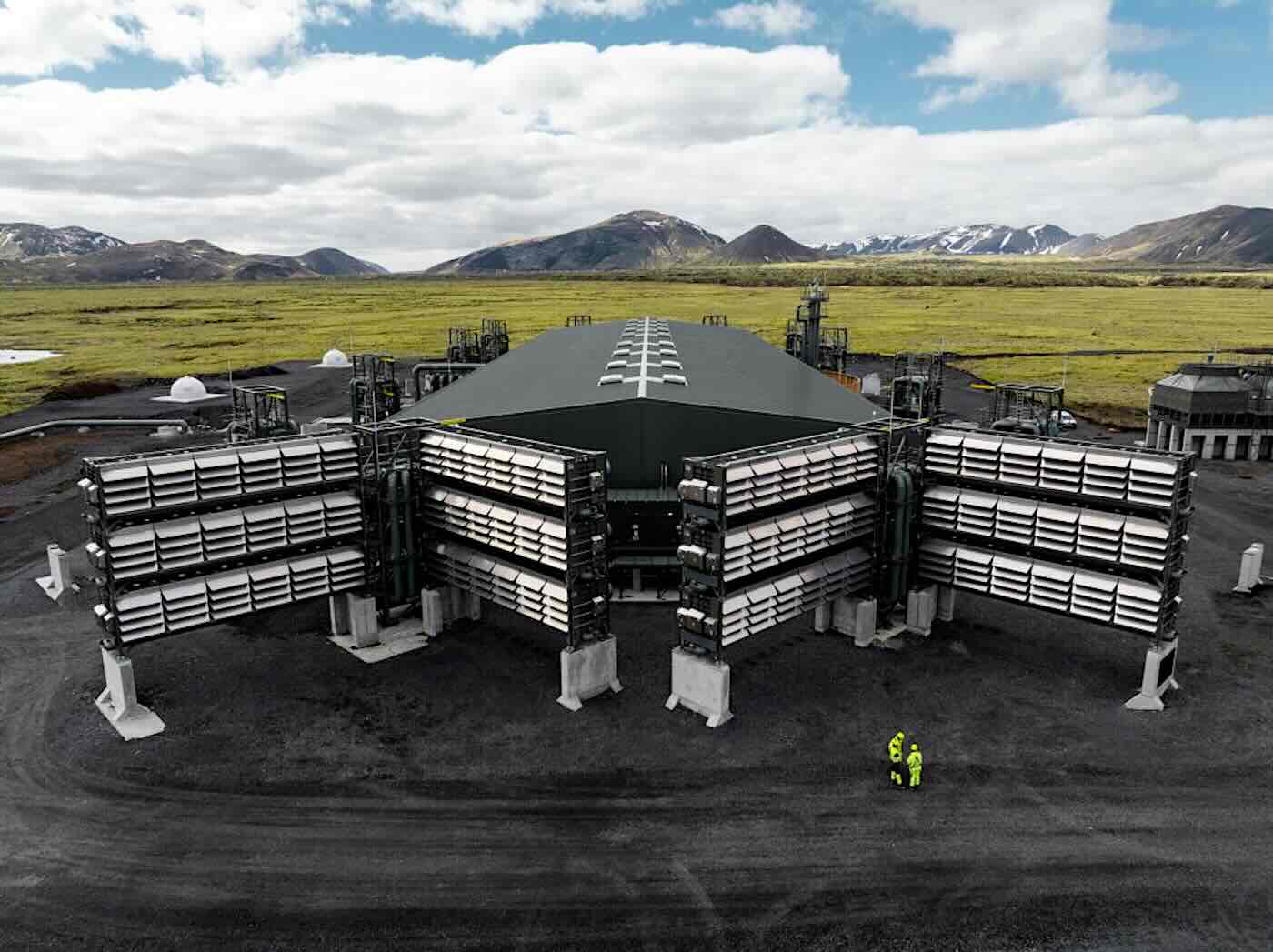

Direct air capture, or DAC, uses technology to extract CO2 directly from the atmosphere and either store or re-use it which has captured the world’s imagination. Proponents argue DAC offers the most permanent carbon removal, yet the technology is unproven at scale.

In contrast, nature-based strategies, such as those used in Michoacan, reduce emissions by harnessing the carbon absorption powers of forests, soil, wetlands and the ocean. Nature-based strategies can also provide important co-benefits beyond carbon removal. For example, sustainable forest management can enhance biodiversity, improve water quality, and support local livelihoods.

Nature-based carbon credits have been tarnished by a series of scandals (well captured in a recent New Yorker article) that charge that early projects did not live up to their promises of removing carbon or benefiting local communities.

While such scandals have shaken market confidence, nature-based carbon removal remains the fastest, least expensive, most scalable approach to atmospheric greenhouse gas removal. As global emissions continue to rise, the need for innovative strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions has never been more critical.

As their voracious appetite for energy to power data centers and AI learning models explodes, companies including Microsoft, Apple, Salesforce, and MercadoLibre have been working to complement emission reductions in their internal operations with the purchase of carbon offsets. Aware of the controversies surrounding carbon markets – including greenwashing, miscounting carbon, and the difficulty of ensuring additionality – they are pushing to improve the integrity of the system with more credible and confident strategies.

That includes investing in nature-based carbon offset projects that reduce emissions and provide additional environmental and social benefits. By doing so, the tech companies are demonstrating their commitment to tackling the climate crisis and building a sustainable future.

In the market’s flight to quality, new actors are emerging. Pachama, a Silicon Valley-backed project developer, is scaling nature-based carbon strategies globally. It harnesses satellite data and AI to empower companies to confidently invest in nature. Singapore-based CIX Marketplace recently released a quality assurance guide that values technical carbon measurement and environmental and social co-benefits alongside risk management and sustainability.

The flight to quality is also supported by actors creating new marketplaces.

Salesforce’s Net Zero Marketplace connects buyers with ecopreneurs, offering a catalog of third-party rated carbon credits. Salesforce’s approach is to complement long-term emissions reductions with high-quality carbon credits.

The Netherland’s Triodos Bank has seeded another innovative platform, the Acorn Framework, to better include smallholder farms worldwide in the emerging carbon markets.

Carbon offtakers

Another critical role played by Big Tech is the sourcing high-quality carbon credits that can drive impact and innovation on the ground.

Microsoft has committed to being carbon negative by 2030, and to removing all the carbon it has emitted since it was founded by 2050. The Seattle, Washington-based company has one of the most rigorous approaches to sourcing carbon removal, focusing on transparency, integrity, practicality, durability, and market transformation. The software giant procures high-quality credits generated by everything from biochar to DAC – and is willing to pay a premium to help support the flight to quality. (Microsoft has an open rolling request for proposals).

Microsoft is also part of Frontier, a coalition including Stripe, Alphabet, Shopify, and Meta, that have agreed to make advance purchases of permanent carbon removal (mostly of the tech variety) to help drive down the costs.

Apple takes a different approach in its quest to become carbon neutral across its entire value chain by 2030. The company prioritizes emissions reductions over removal. In 2021, Apple, along with Goldman Sachs and Conservation International, launched the Restore Fund, an innovative nature-based carbon removal investment strategy. CI is an investor in the fund, and also conducts project-level due diligence to ensure strict environmental and social standards are met.

Last year, Apple doubled down with a $200 million ecosystem restoration and regenerative agriculture fund managed by Climate Asset Management. In March, it brought on two new investors, Apple suppliers Taiwan Semiconductor and Murata Manufacturing, bringing the fund total to $280 million.

The funds aim to remove 1 million tons of CO2 annually, protect biodiversity and support local communities.

Apple’s approach to nature-based carbon offsets is to invest in projects in exchange for a modest financial return coupled with access to carbon offsets; thus carbon credits is a source of revenue rather than simply an offset expense. The funds have partnered with Symbiosis, BTG Pactual Timberland Investment Group and Arbaro Advisors to create sustainably certified working forests on degraded pasture and agricultural lands in South America.

Symbiosis, for example, plans to plant 1 million diverse native seedlings on nearly 2,500 acres in South America this year. BTG’s Timberland Investment Group this week raised $1.24 billion to invest in and sustainably manage mature timberland assets in Chile, Uruguay and Brazil.

Mercado Libre, a South America e-commerce company, has a program called Regenera América to restore Latin America’s unique biomes. In addition to reducing their emissions, MercadoLibre purchases carbon credits mostly from non-profit organizations that restore biomes important for their threatened biodiversity with activities that include ecosystem restoration and local development.

Restoring forests

From my vantage point, living in Michoacan Mexico and having originated and sold carbon credits for 30 years, it has gotten much easier to create and verify high-quality forest carbon projects. Here is just a sampling of exemplary current initiatives:

BioForestal (Mexico). BioForestal Innovación Sustentable combines economic growth for forest owners with conservation of their forests. The company has led the way in testing and demonstrating the Climate Action Reserve’s Mexico forest protocol, which provides standardized guidance addressing eligibility, baseline, inventory, permanence, social and environmental safeguards, and measurement, reporting and verification requirements. They have stepped up to help the Michoacan communities described above sell their verified Carbon Removal Tons.

Generation Forest (Panama). This business group buys degraded agricultural land in Panama and reforests it with native species to mimic naturally occurring rainforests. In line with the principles of generation forests, the projects not only offset large amounts of CO₂ but also regenerate soils, store drinking water, and create habitats for a variety of animals. Their credits from reforestation attract a higher price compared to BioForestals improve forestry management. Generation Forest is ‘sold out’ of its carbon credits having recently signed long-term contracts with two European companies paying $32 per ton for carbon offsets acquired.

ReSeed (Brazil). ReSeed is partnering with Equipe de Conservação da Amazônia (ECAM) to connect smallholder farmers in Brazil with carbon markets. The new partnership aims to support farmers in accessing additional revenue streams available through selling carbon credits, also aiming to avoid continued agriculture-related deforestation in the Amazon. ReSeed is also working with Dengo to add Brazil cacao farmers to the company’s carbon credit program.

Toroto (Mexico). Toroto is a Mexican developer of projects that restore aquifers and landscapes, and sells the resulting carbon credits on the voluntary market. The company has seen 100% year-over-year revenue growth, and is helping to capitalize on Mexico’s potential for 50 million hectares for carbon offsetting. Toroto’s credits from landscape restoration generally fetch a price greater than improved forestry management like BioForestal’s project, but less than Generation Forest’s reforestation, which has significant verified co-benefits benefiting biodiversity and local people (Disclosure: the author is an advisor to Toroto, among other reforesting initiatives).

These projects are leading the way in demonstrating the effectiveness and potential of forest carbon projects while also providing additional environmental and social benefits. They demonstrate the potential of nature-based solutions for addressing the climate crisis and supporting sustainable livelihoods and economic development.

___________________________________________________________________

Shaun Paul is a strategic advisor and impact investor, and the former CEO of Ejido Verde in Michoacan, Mexico.