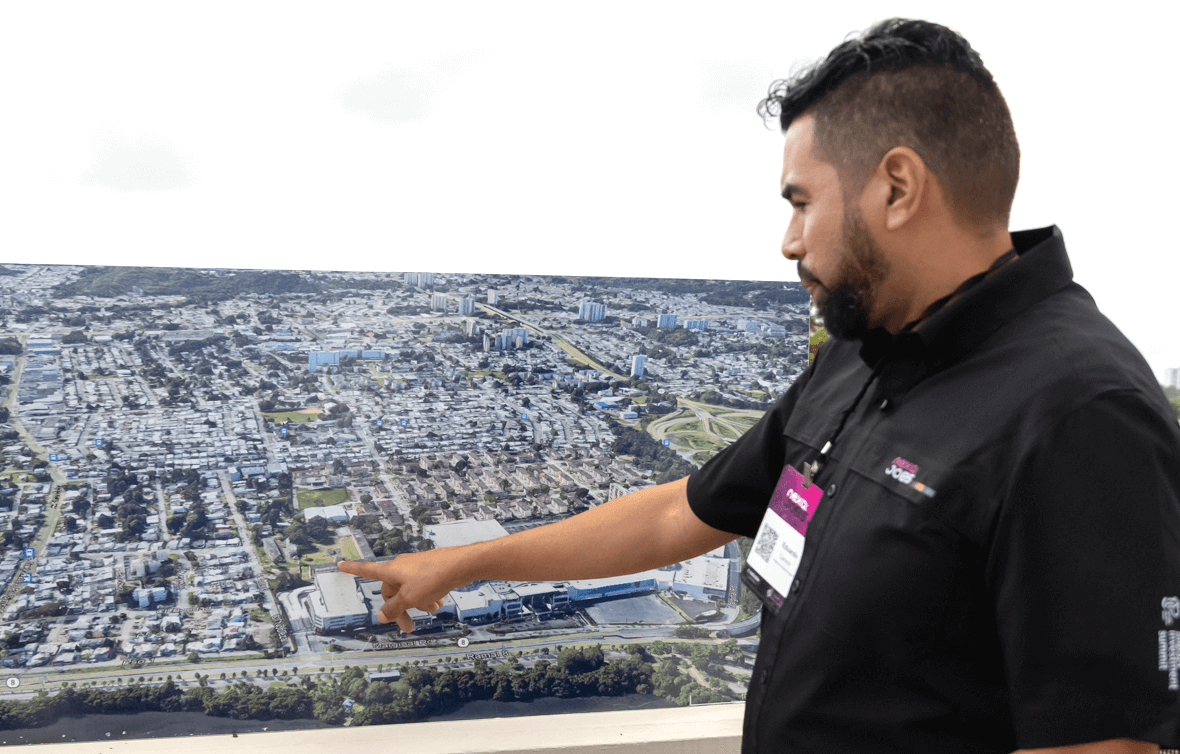

As we design for impact, it’s important to put people at the center of financial structures.

In 10 ways to redesign venture finance for a more inclusive post-COVID world, Aunnie Patton Power highlighted several points that resonated with us as nascent investment managers focused on designing and managing accessible, affordable lending products that support people who face discrimination.

10 ways to redesign venture finance for a more inclusive post-COVID world

In the United States, conversations around where power sits, who controls resources, and who has access to wealth are an ongoing discussion and point of contention as resources and opportunities are statistically siloed based on demographic factors, specifically race. Aunnie’s points around distributed ownership and decentralization of control from the viewpoint of Sub-Saharan Africa and her work globally ring true in this region as well: increasingly, there is a call to redistribute wealth, power and control to people who face barriers due to discrimination based on race, gender, immigration status, and/or sexual orientation.

As impact investors, whether we seek to support entrepreneurs, small business owners, or people in their individual capacity, one thing is clear: we must center people in our investment structures, our investment policies, and our investment mandates.

This is easier said than done – centering people with fewer resources whose networks may not hold positions of power is a process that takes time, shared learning, and empathy. The latter aspect is crucial to our approach and fundamental to the principles that spawned a global movement of impact investing in the first place: at the end of the day, people want to be impact investors because we have empathy for one another and we want to support each other to thrive – why then do we so often lose these values in our investment processes?

As investment structures progress, they are often subject to feedback from a myriad of perspectives, many of which are deeply entrenched in traditional financial systems and risk/return pricing models. While these perspectives are additive with respect to shared learning and expertise, they too often detract from the ultimate goals. As conversations shift towards risk, subordination, benchmarks and pricing, we collectively lose sight of our original goal to support people or catalyze change as the first priority; in short, we subordinate impact in our structures because we are designing for LPs, not the people we seek to serve. This practice must end if we seek to address the detrimental economic ramifications of COVID-19 and build economic equity collectively.

Tools in the toolkit

In her article, Aunnie recommended various tools that may add value to our design process as impact investors, and we know that all of them can be productive when shared goals are centered. But it’s important to remember that all capital allocation and structuring techniques are tools in our investment toolkit. As experienced practitioners, we have seen these tools used in various ways to extract from people and to support people, depending on the shared goals behind the design processes.

As unicorns stumble, investors warm to revenue-based financing for ‘zebras’ and ‘Clydesdales’

Revenue based financing is an easy example: depending on the pricing terms, this tool can be an effective and supportive financing technique that smooths cash flow across seasonal revenue streams, or an extractive financing technique that bankrupts early stage businesses. Depending on the structuring and the underlying terms, the same can be said of venture debt (with extractive or concessionary interest rates) or even convertible grants (with extractive or supportive conversion terms). The point is, regardless of the tool, it’s important to center shared goals and people in our structures, otherwise they will fall flat on achieving our impact goals regardless of their financial engineering.

To Aunnie’s valid point, “Impact Investing was created to revolutionize capital markets”, but instead “we are replicating them.” As we seek to expand our toolkit and “reform the capital system,” we must recognize that tools can be either constructive or deconstructive and ask questions like:

1) What are we building together?

2) What are we dismantling together?

3) Are we truly designing for the people we aim to serve?

4) Are we disrupting or replicating capital markets?

5) Are we remaining in our comfort zones or are we leaning into the unknown?

In a perfect world, we are building equitable structures and dismantling inequality together. We are designing regenerative structures that seek to heal our historical injustices, whether they are social or environmental. We are bringing people to the table who may never have heard of this publication because their radar is what’s in front of them on a daily basis. And we are listening, with patience, not judgment, to each other. From our experience, this is easier said than done, especially as we collaborate across networks that are too often siloed.

Collective experimentation

As we build new structures and experiment with tools, we must also figure out a way to share our learnings, successes and failures transparently. Too often structures that extract from people are hailed as success stories because, from a financial return standpoint, they achieved their goals and outperformed their benchmarks (microfinance that uses traditional pricing models for borrowers is a classic example). In order to understand what’s working and what isn’t, we must ensure the perspectives on what works (and what doesn’t) are diverse and representative of all parties involved in our transactions.

In order to continue experimenting collectively, we must also focus on transparency to avoid reinventing the wheel every time in our design processes. We must reduce costs by increasing transparency, streamlining and sharing templates, and developing structures that can add or remove tools as needed depending on their design goals. If not, the siloed legal fees, fund design fees, and administration fees will be too heavy a burden to bear for community-oriented managers that seek to test new strategies in collaboration with people. Convergence is a good example of this for blended structures in a global emerging markets context, but now is the time to expand and streamline our shared learnings across geographies as income inequalities are exacerbated globally.

While financial skills are important in the context of investment and structuring – nonprofit principles, design principles, collaboration and empathy are increasingly relevant in a post-COVID context. We, as investors, have built the systems that exist and that perpetuate inequality and environmental degradation. In order to change or dismantle these systems, our tools must be adapted and wielded with humility by incorporating a desire to learn from those who we seek to prioritize in the first place.

Sandhya Nakhasi and Ryan Glasgo are cofounders of Community Credit Lab.