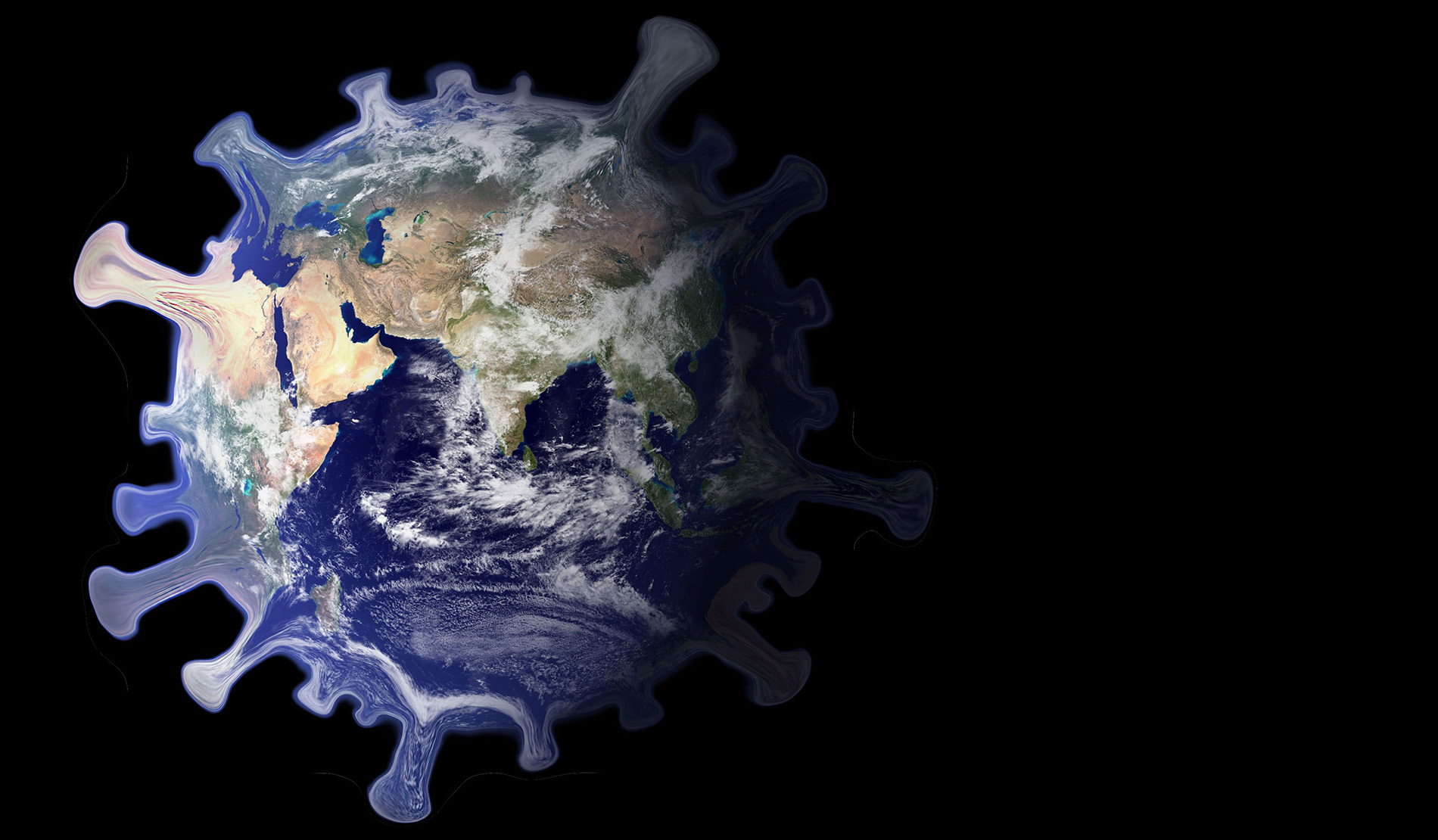

The global experience – and response – to COVID19 is the latest example of history repeating itself.

Very rarely have we experienced events – at least in this era of modernity – that are entirely unprecedented in human history. The epidemics, pandemics and catastrophes that catch us off-guard are often because they are new to our lifetimes, experienced in a new domain, or just simply unexpected.

In the conversation of how to stop the spread of disease, protect ourselves, and put an end to the crippling socio-economic effects of this virus, there is an eerie precedent in the history of climate action.

The history of climate change offers both lessons and warnings. The lesson: A coordinated, global, and equal response for our mutual well-being is necessary. The warning: We have only slowly and haphazardly achieved any such cohesion in our climate response. Now is the time for us to act differently than we have in the past: by accepting our global interconnectedness, slowing and mitigating the effects of the virus without exacerbating systemic inequality, and empowering local leaders to support the communities within which they serve.

With COVID hard upon us, we can’t afford to get it wrong this time.

What climate change teaches us about COVID-19

The evolution of climate change response – and eventually action – reads like a fable for the future. The story of how we got to now has striking lessons for how we choose to respond to the threat of COVID19. Here’s what climate change and COVID19 have in common:

A disregard for physical borders and boundaries. In the early days of coordinated climate action, there was much jest around the nomadic nature of our climate footprint. The emissions produced by a single country don’t stay there and the earth’s atmosphere – which bears the brunt of what we emit – could care less about the borders between countries. COVID19 is not so different. This disease will continue to travel, as we do. Physical boundaries are meaningless in guiding us on how to think – or stop – this disease.

A shared global culpability, responsibility, and eventual benefit. The rollercoaster of coordinated climate action has shown us that a balance between owning the problem and assuming equal responsibility in solving it are necessary to make real strides. The shortcomings of the Kyoto Protocol illuminated this very disconnect in climate response across the globe. We cannot divide this conversation between prosperous vs. emerging nations, or across political lines. Coordinated action is key to our shared prosperity, and that is true within and across countries.

The needed partnership between public will and political action. In hindsight, the Paris Agreement’s widening of the cast of players – namely putting power in the hands of governors, mayors, corporations and civil society – was much of its salvation.

In response to the Trump Administration’s withdrawal from the agreement, many coalitions rose to this challenge. Individual states across the US signed on to the Paris Agreement. Citizen-led coalitions sprung up to mobilize climate education and awareness. Where a leadership vacuum was created, unlikely allies worked together to fill that gap.

In the context of COVID19, governors and local leaders are stepping up to offer guidance, protection and assurance. Communities are banding together to serve one another, and civil society organizations are focusing on protecting our most vulnerable workers. In the fight to preserve our planet, public will has had an enormous role to play. Our individual, local, and community responsibilities in the context of COVID19 are just as critical.

A brief history of coordinated climate action

Climate change research, as we currently think of it, dates back to the mid-1800s. But it wasn’t until the 1970s that it creeped into public discourse, and it wasn’t until unpredictable weather patterns dominated the 1980s that concern transformed into action.

The first coordinated public policy attempt – on an international scale – was the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1991, which 166 nations signed on to. Though this type of coordination was a monumental first step, critics of the framework pointed out that the policy itself lacked punch. It avoided setting any emissions targets to be met, nor did it suggest mechanisms for enforcement.

In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol was created to establish national reduction targets for greenhouse gas emissions, and introduced emission monetization mechanisms to reward and punish emissions behavior. But the Kyoto Protocol lacked buy-in from major developed country leaders, namely the US and Australia. They took issue that the agreement didn’t also monitor, manage, and punish bad behavior on the part of developing countries.

Around the same time, climate change research was coming under heavy fire. Substantial investment by the oil industry and lobby groups helped fuel skepticism around the scientific basis for predicting climate change. The conversation moved from solving the problem to questioning whether there was one in the first place (all while natural disasters were increasing with devastating frequency).

As the debate has raged, hundreds of thousands of lives have been claimed, billions of dollars in damages incurred, and millions of individuals were displaced. It wasn’t until 2015’s Conference of Parties (COP) meeting in Paris that we broke through the conflict-laden fog of emission tracking, targets, and punishment. 195 nations signed on to the Paris Agreement, creating a first of its kind consensus on global climate action (note: the number of signatories would fluctuate in the following three years.)

Unlike the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement established (self-directed) targets for emission performance for all countries, and even proposed a committee of experts to help lagging countries “get back on track.” Its priorities included limiting global temperature rise (by reducing greenhouse gas emissions), instituting mandatory measures for monitoring, verifying and publicly reporting national progress towards emissions-reduction targets and mobilizing financial commitments to support developing countries with mitigation and adaptation. In what would prove to be a critical inclusion – in light of the Trump Administration’s announcement to withdraw the US from the agreement two years later – the Paris Agreement also created a way that local leaders could engage in the fight.

Looking forward

A global commitment will be essential in stopping COVID19 in its tracks. Our approach to successfully slowing the virus’s destructive toll will require coordinated action, global accountability and partnerships with unlikely allies.

But beyond thinking through how to respond to deal with this current crisis, we can’t lose sight of what we’ll need next: to rebuild.

At the local level, nationally-driven solutions to support individuals and small businesses, as well as current efforts to stabilize markets are all immediately necessary. Government relief and assistance is often well-designed (in the places where it works) for moments like these. The next step to avoid repeating our past will be to connect the infrastructure of safety nets with one another, on a global scale.

But the opportunity for innovation – and shaping the future of our interconnected world – is equally seismic. Climate crisis has created new opportunities and innovation in cleantech, renewable energy and energy storage.

Similarly, COVID19 has already illuminated the sectors that need to change now. There’s more we can do to replicate and expand sustainable supply chains, scale new modes for education and healthcare delivery, and reprioritize (and respect) the role that caregiving plays across society. This is also an opportunity to update outdated norms, like the slow drip of traditional philanthropic funding, the value of multi-year non-profit support, and the catalytic impact of bridge loans, emergency financing, and capital that derisks critically needed innovation.

The human ingenuity, unlikely partnerships, and new ways of working that have taken our climate story in a new direction can also guide us through a post-COVID world. One that is mutually prosperous, globally sustainable, and truly inclusive.

Rehana Nathoo is founder and CEO of Spectrum Impact.