Can community development financial institutions be anti-racist?

Don’t answer too quickly. For those familiar with the history of CDFIs, specifically created to align capital with justice, there is a natural tendency to think the answer is yes. This is a White supremacy culture mistake – the idea that our “intentions,” not our impact and results, are what matter.

As financial institutions, CDFIs inherit the very tools of capitalism that have wreaked havoc on communities of color for decades in repeated cycles of cynical wealth extraction. Can any organization overcome that history? CDFIs believe that they can use the tools of capitalism for good. But without deep analysis and interrogation, each tool should remain suspect.

Active anti-racism

To better understand how to answer our question, we first need to spend some time understanding anti-racism. For that purpose, I like to use the “Moving Sidewalk” analogy from renowned psychologist and educator Dr. Beverly Daniel Tatum:

I sometimes visualize the ongoing cycle of racism as a moving walkway at the airport. Active racist behavior is equivalent to walking fast on the conveyor belt. The person engaged in active racist behavior has identified with the ideology of White supremacy and is moving with it.

Passive racist behavior is equivalent to standing still on the walkway. No overt effort is being made, but the conveyor belt moves the bystanders along to the same destination as those who are actively walking. Some of the bystanders may feel the motion of the conveyor belt, see the active racists ahead of them, and choose to turn around, unwilling to go in the same destination as the White supremacists. But unless they are walking actively in the opposite direction at a speed faster than the conveyor belt—unless they are actively anti-racist—they will find themselves carried along with the others.

Much of our nation’s discussion about racism is limited to individual acts of hatred or discrimination – the folks power-walking down that moving walkway. But as Dr. Tatum’s metaphor illustrates, simply being “not racist” (standing still) is quite different from being “anti-racist” (running backward on the moving walkway). Structural racism moves us all toward the same inequitable destination, and we cannot let passivity masquerade as neutrality.

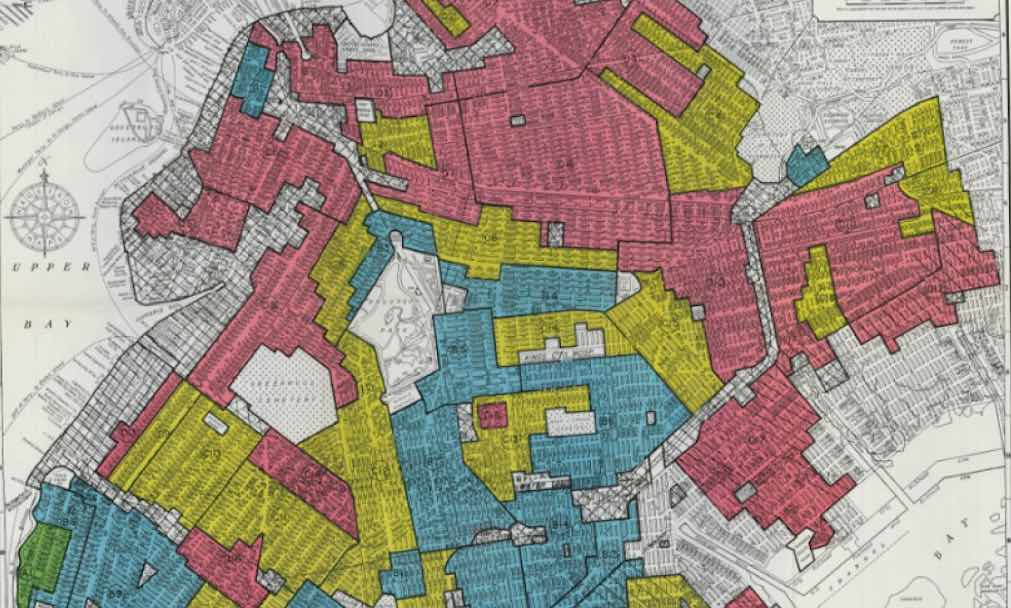

Structural racism is comprised of policies, laws, regulations, and practices that conspire to oppress and perpetuate racial group inequity. It permeates every aspect of our society, from education to health care, criminal justice to residential segregation, employment to financial institutions. The pervasive interconnectivity of the racial “gaps” in our daily life are manifest. The financial institution system is not a neutral party, only reflecting disparities from other inequities. It has been complicit in contributing to the racial wealth gap.

Systemic bias

CDFIs exist in the larger world of this financial institutional system. While our origin story may direct us towards “good capitalism,” and in opposition to many of its bad practices, it is still our system. Many of our staff were trained and acculturated by that world. It comprises the majority of our investors and underwrites our trade associations, conferences, and training. Powerful interests built this system and work to maintain it.

The more we adopt its tools, the more we must resist being sanguine about fighting capitalism’s powerful incentives to be extractive, particularly of the most vulnerable. We must interrogate the role of these tools in inequity and modify them for anti-racism – otherwise, we are simply standing on a moving sidewalk.

“Old bank regulations (redlining) drove down the property/land value for decades, and now current bank regulations prevent investment in those areas where appraised-values are low,” I wrote a year ago in a blog post about the role of appraisals in structural racism. The industry’s use of appraisals is exactly the kind of “neutral” (standing on the moving sidewalk) tool I’m talking about. Its impact is that of a blunt instrument perpetuating inequity and is so inexorably woven into our underwriting and risk management protocols that it is the very essence of structural racism. For 25 years, IFF has based its loan amounts on 95% of total development costs, greatly reducing the “equity” that nonprofit borrowers needed to create a vital community facility.

Restorative-justice capital

I believe that CDFIs can become anti-racist and anti-oppressive if we understand that we must be in an intentionally active role – turning and running against the moving sidewalk. We don’t have a playbook for becoming anti-racist financial institutions. Each CDFI’s racial equity journey will follow different paths. IFF’s journey started four years ago, and sometimes we feel like it was yesterday.

Since we began our journey, I have tried to have as many conversations about becoming an anti-racist CDFI as possible, and it is very clear that we all have a very long way to go. That said, I humbly offer a few ideas for discussion and examination.

Start with your people, your organization. Organizations are only as good or anti-racist as their people. We can never underestimate the power of White supremacy to create myriad implicit biases that surface in our daily interactions and mental models in designing our programs and products. That’s why CDFIs should consider “anti-racism professional development” just as important as underwriting training or other technical skills.

At IFF, we have committed to providing every employee with an intensive 2.5 day anti-racism/anti-oppression training – a significant investment, but also one we realize is merely a first step. Training alone doesn’t magically turn us into a super-woke, anti-racism crime-fighting squad, but it does ground us in the same foundational knowledge and language for having courageous conversations about un-doing a long-standing system of oppression. Ongoing dialogue and training enables us to be better aware of what Dr. Tatum called the “smog” of racism – sometimes thick, other times less apparent, but always around us.

Stop extracting wealth. A CDFI’s process for interrupting racism must begin with interrogating the tools we have adopted from the financial services industry. Two examples: nonrefundable application fees and risk-based pricing. IFF has rejected these practices since our inception in 1988 (though at that time, we weren’t thinking about our policies in terms of racial equity; we were using a kind of ‘nonprofit equity’ lens that forced us to deconstruct the challenge of lending to nonprofits that serve lower-income communities). But the policies are so common that almost every management consulting firm we’ve worked with has suggested that we start using them.

If you’re a CDFI working with people of color and you’re charging application fees for them to apply to get your product, you should re-think that practice. Consider this:

- If the application fee is small, why bother?

- If it is large, you’re actually asking your customers to reduce their wealth to fulfill your mission and use your product.

- For those that you turn down, you have actually reduced their equity – walking them back a few steps from the starting line of getting credit in the future.

- If your data shows that you are turning down more people of color than White applicants (and yes, you should be measuring this, to understand if you have implicit biases), then you are accelerating the moving sidewalk.

Risk-based pricing, or RBP, the practice of assigning higher interest rates to “riskier” applicants based on historic algorithms, is steeped in racial bias. When we use RBP, we are literally charging people of color more than White people for the same product. The borrower either ends up paying us more than they should have to, or they aren’t able to repay the loan because we’ve made it harder for them to do so (and then we feel justified in the predictive nature of our RBP!).

Subprime lending is the most egregious example of RBP extracting enormous wealth from communities of color. But those unregulated, for-profit mortgage brokers are not the only culprits. Many CDFIs entered the fray, providing “good” capital with many of the same extractive practices. That kind of practice might be considered not only standing still on the moving runway, but actively walking forward on it; anti-racism work should be about erasing wealth and income gaps, not doubling down on them.

Interrogate products, services, and practices. To become anti-racist, CDFIs must shed or significantly change all tools that are extractive or heighten inequity. This starts by systematically interrogating our practices, products, and services:

- How does this tool truly help us do our work?

- Does this practice actually provide true risk mitigation, or is it just perceived? Where did those perceptions come from? Did they come from the banks that invest in us, and where many of our employees used to work?

- Do we know who most benefits from our products? Who is most harmed?

- When people of color apply, do our products work for them, or do our products fail them?

This interrogation process must be brutally honest – and therefore almost certainly requires your staff to engage in intensive professional development around anti-racism and race equity (see above). This courageous conversation must be done with an equity lens, not an equality one. The difference is vitally important for an anti-racist CDFI. Is the goal of your investigation to show that everyone, regardless of race, can access your tools (equality), or that everyone, regardless of race, successfully leverages your tools (equity). For most CDFIs, the nature of our work often boils down to picking winners and losers (equality), but the real mission of our work is to align capital with justice (equity).

Honest interrogation of our loan underwriting policies and practices will surface one of the following:

- practices that do not create or perpetuate inequity;

- practices that result in inequity, but that can be dispensed with or significantly modified going forward; or

- practices that result in inequity, but that we can’t change because we believe they are fundamental to risk management and fiduciary responsibility.

At IFF, we often cite our choice not to use appraisal value to determine our real estate loans as an example of “b.” We have lent over a billion dollars on community facilities without basing loan values on appraisals or risk-based pricing, and our portfolio performance history matches that of traditional financial institutions.

And there are other examples from the CDFI space. Take our colleagues at Allies for Community Business (formerly Accion Chicago), which recently announced they would no longer determine their microloan approvals using credit scores or collateral value (both of which adversely affected business owners of color). By modifying their approval practices to use the credit report components that best predict loan repayment and are more equitable, and by eliminating altogether the value of collateral as a loan-sizing mechanism, Allies is leveling the playing field for all borrowers.

Scenario “c” is the most difficult to interrupt – and that brings us to the continuum.

Engage (and invest) in a continuum of activities. If we can’t change a practice that results in inequity, we must do something else to help the borrower overcome that inequity – that’s where technical assistance, capacity-building programs, and other common CDFI activities come into play.

Last year, I published an article about the continuum of the activities CDFIs need to conduct to build a pipeline of “investable projects” in under-resourced communities. Those continuum activities are very much what CDFIs need to do interrupt the moving sidewalk and be anti-racist; they acknowledge that we have an enormous role and responsibility to reverse decades of underinvestment and inequity. Being anti-racist requires action!

Here’s an example of what this looks like in practice. Homewise, a CDFI in New Mexico, is obsessed with helping low-income, Latinx families afford/purchase homes as a wealth-building strategy. But they don’t just provide home mortgage products; they also provide multiple continuum activities designed to help families qualify for the best mortgages, at the best rates, with the lowest fees. Through deep engagement with families, training, and coaching, Homewise helps families improve their credit scores to qualify for lower-rate, prime mortgages. Prime mortgages save their families thousands of dollars, increasing their buying power and wealth and avoiding the wealth extraction of subprime mortgages.

Homewise also designed a second-mortgage product that lowers the mortgage loan-to-value ratio, which helps clients avoid expensive private mortgage insurance – again, increasing families’ buying power and decreasing wealth extraction. These products and activities combine to correct historical inequities and increase family wealth for Latinx families.

Other examples of CDFI Continuum activities that decrease inequities can be found on my blog: Capital Impact Partners’ Equitable Development Initiative in Detroit, and IFF’s Stronger Nonprofits Initiative in multiple Midwest cities.

Refuse to ask for permission. At the Opportunity Finance Network conference last fall, representatives from IFF, Capital Impact Partners, and US Bank facilitated a robust conversation about how CDFIs can create new products that interrupt decades of racism. Unfortunately, the Zoom chat box was consumed with one question: “What will the investors think?”

As a leader of a CDFI that must raise upwards of $40-50 million of long-term capital each year, I am acutely aware of the pressure to make our investors happy. But anti-racism training encourages us to stop defining every challenge in debilitating binary options (either/or thinking). CDFIs can be concerned about their investors and change how our products and practices conspire against communities of color.

The bottom line: CDFIs will never become anti-racist if we continue to be obsessed with what our investors think about our interruptions. Now is not the time to ask permission to be anti-racist. It is a time to innovate restorative justice capital and practices that interrupt the legacy of racism in our communities.

After all, that kind of bold thinking – thinking that differs from the financial institution system – is what got CDFIs started. We were created because the financial institution system was not reaching all communities, and those institutions did not invest in us because we were too radical. Our first investors were the Sisters Religious, who held deep commitments to their missions of justice and who understood our ‘bold’ idea to bring capital to all communities.

Today, things are different: Financial institutions now comprise the majority of CDFIs’ investments. The larger volume of investments has been a blessing, allowing us to reach more communities. But those same investments are also a curse if they require us to ask permission to walk against the moving sidewalk.

Financial institutions and impact investors need their own anti-racism journey. Some, like US Bank, have courageously delineated a vision and are encouraging others to do the same. I believe CDFIs can educate investors on “real” versus perceived risks based on our implicit biases about people and places – the “smog” of racism we all breathe. We need to encourage our investors to get on the journey with us, but we cannot wait for permission.

Disrupting the cycle

Yes, I believe that CDFIs can become anti-racist. And yes, this article includes some suggestions for how to begin: equipping our staff with the tools to interrogate; ridding ourselves of products and practices that extract wealth from communities; questioning and evolving every product and practice with the goal of equity; investing deeply in Continuum activities that level the playing field; and refusing to ask permission to be anti-racist.

But there will not be a paint-by-numbers approach for all CDFIs to follow. Each of our journeys will be long, and different. And each CDFI will bring its past to this moment.

Our task is to always ask: why isn’t there equity here, in this place, in this sector, with this product or service? Every answer must be interrogated further – why, and why, and why? Only then can we begin to peel back the onion of our racist past and disrupt the cycles that hold back communities of color. Only then can we create new tools on our journey walking against the moving sidewalk.

Joe Neri is Chief Executive Officer of IFF, a Chicago-based community development finance institution