Five early-stage startups in Tunisia beat the odds of fundraising in a declining venture market last year, collectively raising $10.3 million with the help of a blended finance approach from USAID. The companies benefited from a new spin on a structured finance tool called a first-loss tranche, which reduces risk for investors and increases their willingness to take a chance on a company.

Fund managers, capital providers, advisory firms, and start-ups can learn from this approach to fundraising in a challenging market or during an economic downturn. The right type of concessional support can be especially helpful to impact-minded entrepreneurs in emerging markets now facing decreasing GDP growth, high inflation, and/or liquidity constraints.

Consider Tunisia. The North African country of just over 12 million people “is a small market, but it has a strategic geographic position,” says Malek Lamouri of CrossBoundary, an emerging markets transaction advisory firm and USAID partner. “It is the gateway to other neighboring markets in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.”

The country also has a well-educated population, with strong female economic participation and a culture of entrepreneurship. Hindering the success of its budding startup sector, however, is poor access to finance: almost 44% of Tunisian businesses report this as a barrier to growth.

To help companies overcome Tunisia’s macroeconomic challenges and secure investment, CrossBoundary and startup accelerator and investor Flat6Labs used grant support from USAID’s INVEST initiative for a first-loss mechanism to crowd in other investors in Flat6Labs’ portfolio companies. The pitch: If an investment does not perform as expected or begins to lose value, investors would be protected from loss by the first-loss, equity-like layer.

For the startups, the first-loss financing is structured as a zero-interest subordinated note — essentially a repayable grant – of 6.25% of the additional private capital they raise. The percentage has been enough to crowd in investment without distorting the market. Once investors are repaid, the first-loss funding can be recycled into Flat6Labs and invested in other startups in the ecosystem.

“This structure provides additional liquidity in the form of non-return-seeking capital to startups, allowing for a higher rate of survival in the economic downturn post-COVID,” says Lamouri. “It also improves the risk-return profile of the companies, reduces barriers to investment, offers protection to investors, and maximizes the catalytic impact of donor funding.”

Crowding in investors

USAID INVEST, CrossBoundary, and Flat6Labs first used this first-loss mechanism in early 2022 to help Tunisian edtech venture GoMyCode close a $7.8 million Series A round, the largest edtech round at this stage on the African continent.

GoMyCode offers cohort-based training programs for high-demand tech skills, including AI, cybersecurity and web development. The company says the average student sees their salary increase by 45% after completing the program.

“You can get a job with a US or European company, earn currency in dollars or euros, but stay in your country and contribute to the local economy,” says GoMyCode co-founder Yahya Bouhlel. The program is affordable, costing about $1,000, or one month’s salary for a software engineer.

When raising its Series A round, Bouhlel says the first-loss mechanism incentivized backing from other investors. “We said, ‘Listen, we have partners who are willing to take the risk with us and are willing to contribute to the project,’ and that helped make the deal attractive, and it gave much more resilience and credibility to the deal.”

The funding has enabled the company to expand from 12 schools to 45 in less than two years. GoMyCode has hired 170 new employees and 900 teachers, grown its student base from 2,000 to 6,000, and set up operations in nine countries.

The experience in Tunisia has shown that a tailored, first-loss mechanism, alone or in partnership with an incubator, can work in places where access to finance is a real challenge for companies, especially in difficult fundraising environments. It’s an area of significant experimentation and learning for the donor community, but it offers a potential pathway to sustainable and scalable results.

Funding before the raise

Startups and early-stage companies often need advisory services to support them on early fundraising efforts. While transaction advisors operate in frontier and emerging markets, smaller deals often aren’t commercially viable for transaction advisors, so they need donor subsidy.

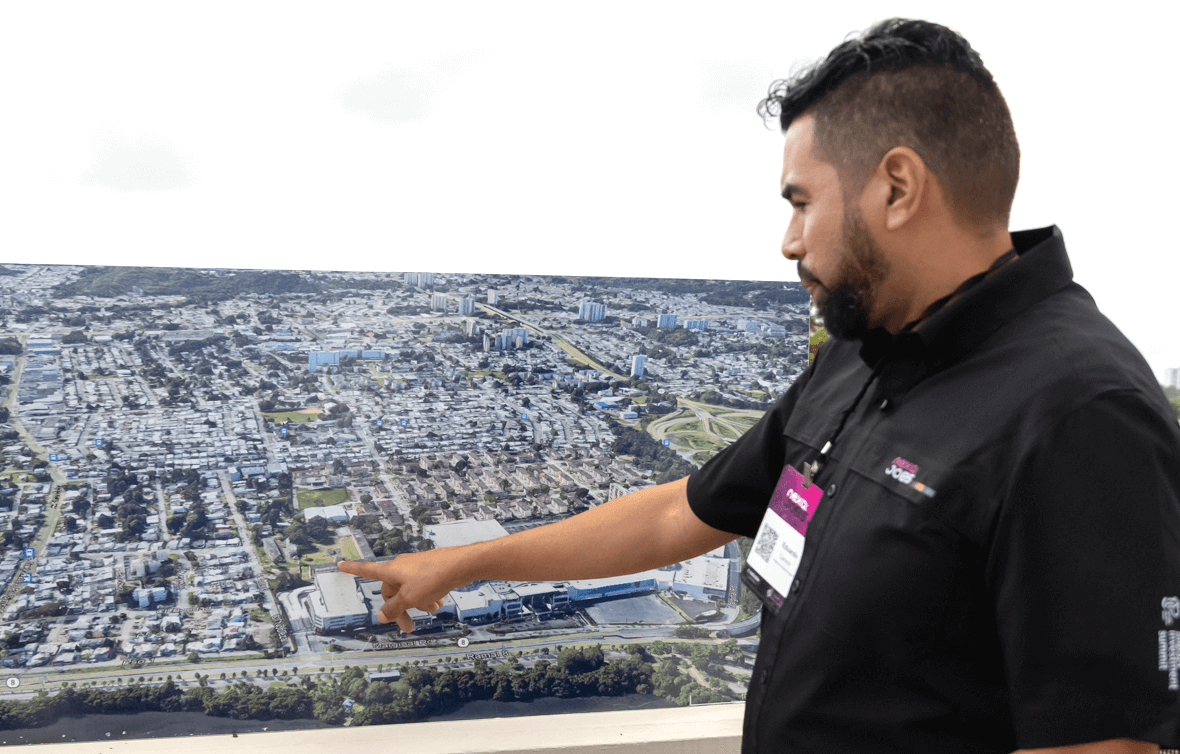

Tunisian deep-tech startup Kumulus makes machines that extract and purify drinking water from humidity in the air – an increasingly crucial climate innovation in a water-scarce country. The company hopes to reduce single-use plastic water bottles, provide a reliable and sustainable source of drinking water, especially for schools and community projects, and create high quality jobs in Tunisia. Research and development for such a technology is costly, however.

Kumulus sought advisory services from CrossBoundary ahead of its $750,000 investment round. Funding from USAID INVEST paid for CrossBoundary to build an investor pitch deck and other materials for Kumulus, and to make connections with investors.

“Working on a financial model would have taken me three or four weeks, and that’s a killer for a CEO,” says Kumulus’s Iheb Triki.USAID has used transaction advisory support and catalytic funding in dozens of markets around the world to support local businesses. Blended finance approaches that use donor funding to catalyze well-aligned private capital can be a lifeline for local businesses, and they can help companies reach their potential in solving problems, creating jobs, and providing the goods and services communities need to thrive.

Kristin Kelly Jangraw is the director of communications for USAID INVEST.