Americans are admonished that opportunity is available to those who are willing to “pull themselves up by their bootstraps.” Let’s measure how long those bootstraps are for certain Americans.

Before COVID, the net worth of a typical white family was nearly ten times greater than that of a Black family — $171,000 versus $17,150. The pandemic hit people of color the hardest – with Black Americans suffering higher rates of job loss during COVID than anyone else. People of color make up at least half of the low-wage workers in America – who were hit hardest by the pandemic. Even that figure is likely underreported as 93 percent of undocumented U.S. immigrants are people of color. Women of color disproportionately hold low-paying essential jobs, accounting for 53% of workers in the food service industry and 80% of workers in the health and social assistance field.

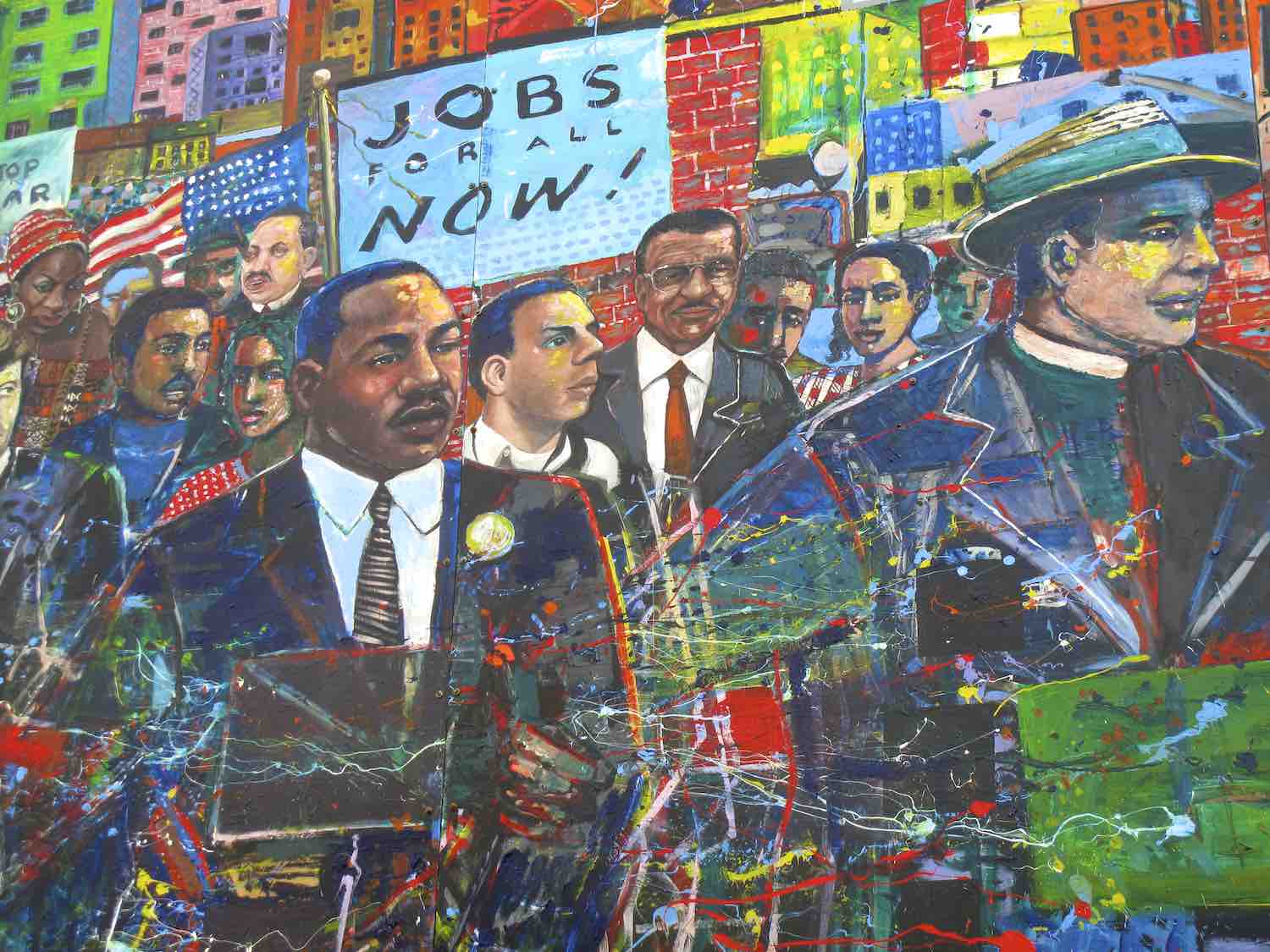

The fact is, in the U.S., race and where you’re born (factors outside our control) still affect your chances to earn a good salary and build wealth more than almost anything else. And the pandemic has made that worse. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., said, “…It is cruel jest to say to a bootless man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps.”

COVID-19 unmasked systemic racial and economic injustice in the United States of America, and social justice protests following the brutal murder of George Floyd were a turning point for many citizens, allowing more people to acknowledge the disparities experienced by people of color, including the income and wealth gaps. Over this unprecedented year, the racial wealth gap has widened even further. Small business owners of color have permanently shut down their businesses after being denied or simply not qualifying for capital to sustain their business during the pandemic.

As The Brookings Institute has detailed, policies to stop Black people from moving up the economic ladder began before there was even a United States – and these policies have impeded Black Americans from building wealth. Black Americans faced 246 years of chattel slavery. Following the Civil War, Congress mismanaged the Freedman’s Savings Bank, leaving 61,144 depositors with losses of nearly $3 million in 1874. Tulsa’s Greenwood District, with a population of 10,000 that thrived as “Black Wall Street,” was decimated by a white rioters in 1921 – one of many Black communities massacred before, during, and after Reconstruction.

Our own parents and grandparents grew up with discriminatory policies throughout the 20th century. The Jim Crow “Black Codes” strictly limited opportunity in southern states. The New Deal’s Fair Labor Standards Act contained an exemption for domestic agricultural and service occupations, where Black Americans disproportionately worked. Redlining prevented Black Americans from opening a bank account, starting a business, or owning a home in certain neighborhoods. Federal rules restricted Black Americans from the benefits of the GI Bill, like home ownership and college education. Home ownership has been the biggest driver of wealth between generations, and programs like the land grant program and Freedmen’s Bureau actively excluded Black participation.

While our generation may not have been alive during when the worst of these abhorrent policies were in place, that does not mean we are immune from their legacy. As two women of color, we can speak about the value of the American Dream – and what it takes to pursue it. Home ownership is one of the most critical drivers of building wealth over generations. The Federal Reserve reports that the average homeowner had a household wealth of $231,400, compared to just $5,200 for the average renter.

Even though relatives on both sides of Donna’s family were life-long renters, her parents were determined to buy a house – the first and only one they ever owned. It was important for them to say they owned something that could be passed down to their six children. As an immigrant child, Bulbul observed a similar passion in her father to become a homeowner soon after moving to the U.S., even though funds were tight. He was determined to put roots down and provide some shelter and economic security to his family in this new land.

This is still true of many people in our communities. And even as some of the more overt discriminatory policies are eliminated, there is less of a clear path today on how to achieve their dreams. The collapse of the housing market in 2008 (by predatory subprime lending practices which disproportionately targeted Black communities), and the Great Recession that followed wiped out half of Black wealth. Black families have been slower to recover, in no small part because they’re still rejected for mortgages at more than double the rate of white families. And, to this day, Black entrepreneurs are more than twice as likely to be denied loans by a bank than a white entrepreneur, even with comparable businesses and credit scores. This is despite the fact that Black people -– and especially Black women – are the fastest growing segment of American entrepreneurship, largely out of income necessity. Black women are 300% more likely to launch a new business than a white person. While research has found that Black entrepreneurs experience greater upward wealth mobility than Black workers – and on par with that experienced by white entrepreneurs – Black-owned businesses are also less likely to remain open than white-owned businesses.

Putting mission first

If we’re going to build forward better for Black business owners, their families, and their workers, we need to take this opportunity to break with the past and create systems that meet business owners of color where they are. Women of color account for 89% of the new businesses opened every day, but almost 75% of women of color say their most common obstacle to growth is a lack of capital. It’s well known by now that just 1% of venture capital dollars are invested in Black founders. The vast majority of major bank loans and SBA loans are inaccessible to Black business owners because of restrictions around minimum credit scores and collateral that Black entrepreneurs often do not have. Many entrepreneurs of color also say they lack access to advisors and networks that could help their businesses thrive. All of this puts these entrepreneurs at a disadvantage.

Too many banks, SBA lenders, and startup investors are failing communities of color. This is where community development financial institutions have a critical role to play. CDFIs have been responding to borrowers in crisis on multiple fronts: providing affordable working capital, advocating for new sources of capital and grants, pushing for changes to the Paycheck Protection Program and other relief programs to benefit Black-owned businesses and small businesses in 2020, and this year working with the Biden Administration to make the COVID response and financial stimulus and jobs plans more equitable.

CDFIs have a long history of effectively helping Black entrepreneurs start and grow businesses, and getting Black families into homes, beginning with the first Black credit unions and banks in the 1930s. In 1994, the establishment of the CDFI Fund at Treasury during the Clinton Administration more than doubled the number of CDFIs in the U.S. from 300 to 615. Today, there are more than 1,000 certified CDFIs in the country.

However, some CDFIs unfortunately fall into the trap of perpetuating restrictive lending practices – because agreements with banks and investors stipulate rates and returns that effectively exclude many Black business owners, and elevate financial return over impact. That is perpetuating the same problem of exclusionary terms and rates at the expense of meeting the mission for which CDFIs were created: to turn that problem on its head to serve economically-distressed neighborhoods and communities of color. And without dismantling that donor-recipient construct, we won’t be able to close this gap, or show up with more restorative practices that our communities need.

Meeting the moment

At the same time, we at Pacific Community Ventures and Appalachian Community Capita are keenly aware that CDFIs like ours have a lot more work to do. Every CDFI should be asking itself two critical questions:

1) Are your products and services designed from a community-centered design mindset, or by the mainstream financial industry?

Even before COVID hit, roughly 8,000 small business loan requests were declined by banks each day across the U.S., and SBA and bank lenders almost universally require a 620 credit score or higher and minimums of time in business and annual revenue to qualify for loans. Black-owned businesses tend to be smaller, younger, and owned by entrepreneurs whose credit scores are on average lower than white counterparts and below what banks and the SBA look for. PCV changed the way we deployed our lending over the last few years, because lending to bank or SBA guidelines meant largely excluding Black-owned businesses. ACC and its CDFI members have established programs and funds for Black and other minority-owned businesses in a region where one often presumes (incorrectly) there is no diversity. Many CDFIs, including ours, do not require minimum credit scores or collateral. We also offer robust mentorship programs, not only to our own clients, but to under-estimated entrepreneurs nationwide, and continue to be on a journey to dismantle power structures within our work and ecosystem to ensure more community governance. That includes focusing on small businesses owned by entrepreneurs of color most at risk of displacement and gentrification in economic cycles, including in these times.

2) What should you dismantle within your investing to start shifting the funder-driven paradigm towards more inclusive approaches and maximize for mission?

We need new leaders of color coming in to re-think products and services that center the needs of our communities and those we’re designed to serve. Then, we need to bring these new ways of thinking back to our funders. For example, we can look across our products to ensure that they are offering restorative, not extractive forms of capital – like equity investments in Black-owned businesses and convertible notes; change underwriting to be inclusive and shed credit scores, collateral, and other barriers; and actively seek out mission-based investors and funds to align values and capital with.

CDFIs like Appalachian Community Capital and Pacific Community Ventures exist because of banks’ lack of presence in communities of color and economically distressed communities. CDFIs have long been “first responders” to many small and growing businesses in communities throughout America and are very much on the front lines of the economic response to COVID-19. Small businesses are struggling to survive, which will impact all our local communities, and our way of life. It is up to us to meet the moment, to internalize the goal of closing the racial wealth gap, and make sure our missions and how we deploy capital reflect that.

Donna Gambrell is President & CEO of Appalachian Community Capital, where she is responsible for attracting and directing investments to community development financial institutions (CDFIs) and mission-driven lenders that are ACC members. Bulbul Gupta is President & CEO of Pacific Community Ventures, a CDFI for California-based small businesses.