Back in the halcyon days of 2015, nearly every country in the world signed on to a set of 17 audacious goals for 2030, including “End poverty in all its forms everywhere,” “End hunger,” and “Achieve gender equality.”

Five years into the 15-year timeline for achieving the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals, many public and private institutions have mapped their activities against the goals and even begun to align their investments. Yet most indicators suggest that despite some progress, the world is not on track to meet the 2030 goals, the global response has not been ambitious enough and in some areas earlier gains have even reversed.

“The positive news is that more and more people know what we are talking about,” Bertrand Badré, CEO of Blue Like an Orange Sustainable Capital, says on the most recent ImpactAlpha podcast. “The negative news is there is not enough action.”

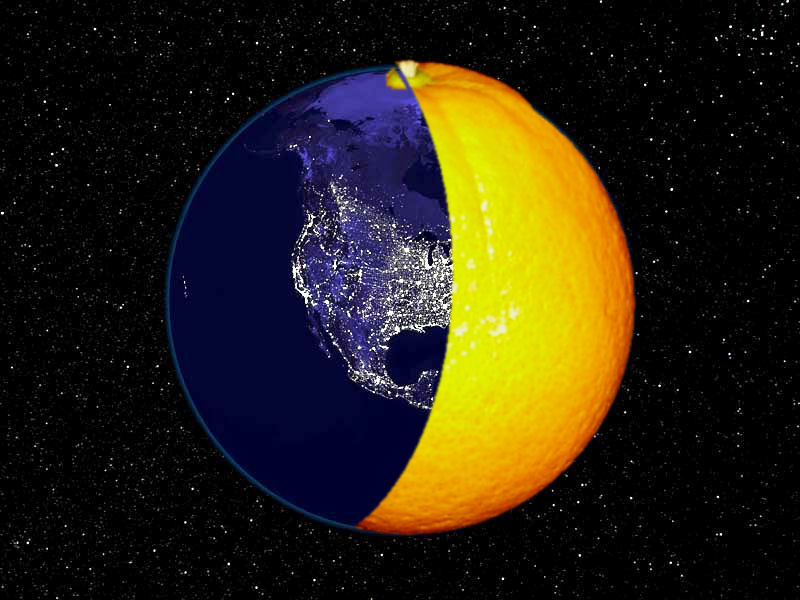

Badré, the former chief financial officer for the World Bank, launched the fund in 2017 – the name comes from a poem by the French surrealist Paul Éluard – to model a private-capital approach to financing the goals. Back when the goals were being developed, he says, “We gave more thought to the goals than to how to get there.”

“The underlying financial framework was: ‘Assume we’ll find a way,’” he says. “We never really discussed what was needed to change the financial system — public and private — to get there.”

The mezzanine-debt fund has made three investments in Latin America to date and expects to close several more in the next few months. To share its early learnings, Blue like an Orange is releasing its internal rating system, SDG Blue, which scores investments against the SDGs in much the same way Moody’s scores companies’ credit ratings.

“We wanted to find a way to take the SDGs seriously and have a guide for how we select deals, diligence deals and how they move through our process,” says co-founder Suprotik Basu. “There’s a real temptation to back into the icon or the goal that makes sense, and that’s how you get to your SDG impact. That didn’t feel right to us.”

Blue like an Orange selected four sub-goals it considers mandatory for all investments: job creation (No. 8), gender equality (No. 5), sustainability (No. 12) and innovation (No. 9). Together they account for 45% of an investment’s score. Another 55% comes from goals specific to a company’s area of activity. Companies can get a 10% bonus by targeting a supplemental goal. Specific indicators are agreed upon to measure progress toward the goals and scores computed. Performance need not be stellar at the outset: the minimum threshhold for investment is 6.0, effectively a ‘D.’

BlueOrange scored its investment in Cabify, a ride-hailing service popular in Latin America, on the basis of gender equality. The company, which has made specific commitments to the safety of women drivers and riders, got a gender-equality score of 6, Basu said. The company, which claims to be carbon-neutral, got a 7 on climate action (Goal No. 13); Cabify tracks the age of its fleet of vehicles, on the assumption that newer models are less polluting. It got innovation points for the ability of its app to track usage in underserved areas; a pilot project in Lima is testing pricing models to encourage use of the ride-hailing service in poor neighborhoods.

Is another ride-hailing app really what’s needed to meet the Sustainable Development Goals?

“When people think about impact, a lot of people think about climate, or agribusiness or health care at the bottom of the pyramid,” Basu acknowledged. “But if you look at the SDGs, the 17 goals and targets and indicators, they are a broad framework for sustainable development. If you take the goals seriously, you’ll find that companies like Cabify knock it out of the park.”

Badré, the author of “Can Finance Save the World?” (2017), is working on a new book on the the systemic changes needed to make the transition from the 40-year reign of “shareholder primacy” to a new model of “stakeholder capitalism.”

“As long as we don’t change it for real – that means changing the accounting rules, the compensation rules, the way you define internal rate of return, the ways to integrate externalities like the price of carbon today and the price of nature tomorrow, the way you report and disclose – the system will not change,” he says in the podcast.

“As long as you don’t change the system, as long as you have no incentive built into the system to do the right thing, it’s not going to be enough,” he continued. “We have to do our best – this is our responsibility – to go way beyond that. That is really the fight of this generation.”