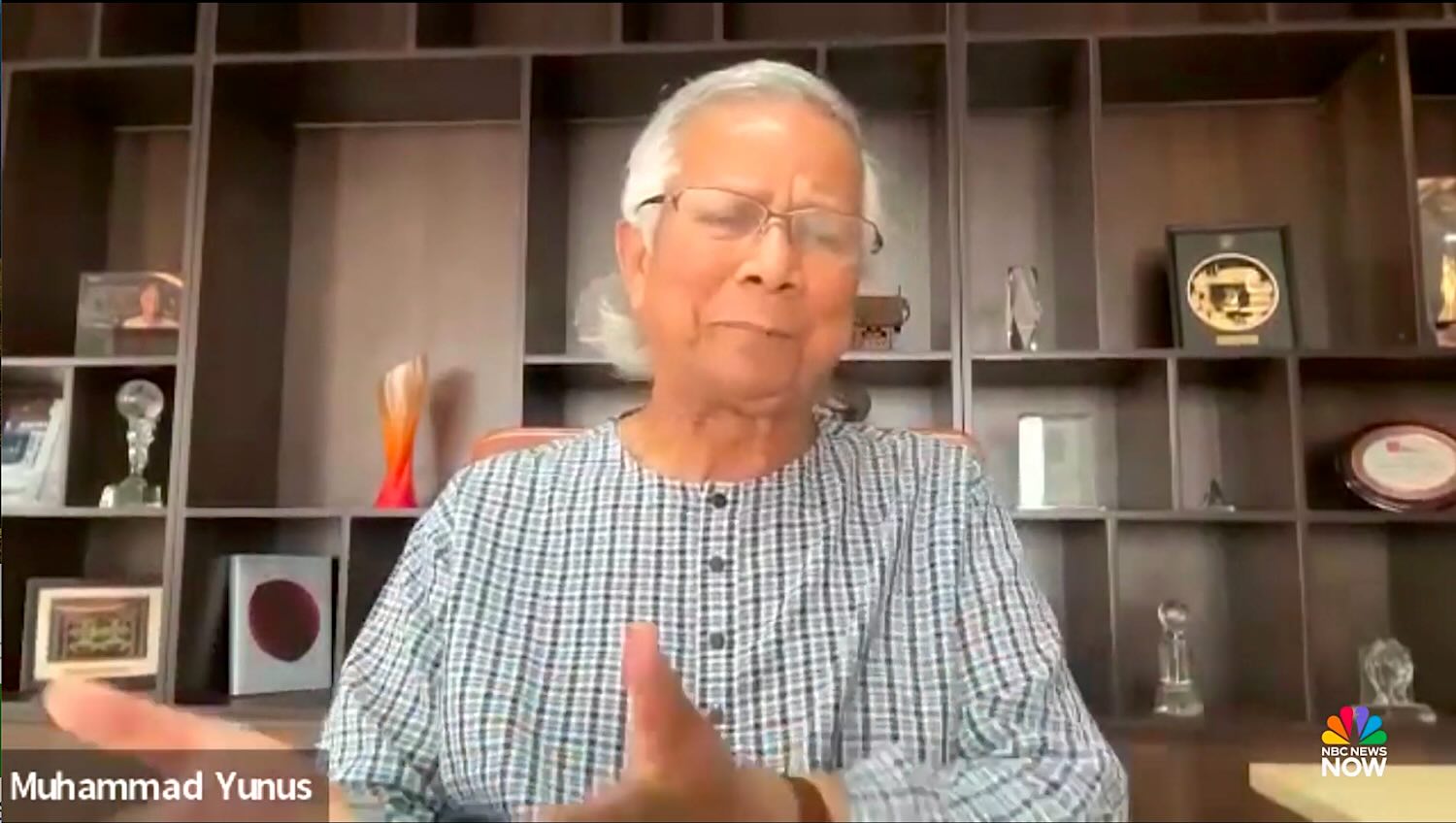

ImpactAlpha, March 11 – The decade-long vendetta against Grameen Bank founder Muhammad Yunus by the prime minister of Bangladesh is escalating toward a showdown that could send the Nobel Peace Prize winner to jail.

Even as Yunus, now 83 years old, has managed to stay out of prison, the legal attacks by the government of Prime Minister Sheik Hasina Wazed have set back the work of the dozens of Grameen-linked firms and worker-owned cooperatives that Yunus founded and that have helped halve the country’s poverty rate since 2006.

Last month, armed men raided the offices of Grameen Telecom, claiming that Yunus and his managers were usurping government property. The men chained shut the doors of the modern office complex in the capital Dhaka that houses several of the 50-odd Grameen-associated companies, and took over their offices.

“She hates me,” Yunus said of Sheik Hasina in an interview with NBC News after the raid. “She sees me as a political threat.”

The crackdown comes at a perilous moment for Bangladesh, as its impressive economic gains are threatened by rising energy costs, inflation and post-pandemic recovery.

Earlier this month, Yunus won a brief reprieve from a six-month prison sentence. He was convicted on New Year’s Day – a week before Sheik Hasina was re-elected – on charges of diverting $2.5 million in dividends from the Grameen group’s telecoms company rather than pay the dividends to the company’s workers. That trial was denounced as politically motivated by several hundred Nobel Prize winners and other public figures.

Sheik Hasina in 2011 had already removed Yunus as head of Grameen Bank, installing her own lieutenants. But until recently she had kept her hands off most of the other Grameen enterprises, including the telecoms group, a textile company and a joint venture with Danone that makes enriched yogurt for underfed children.

Yunus, free on bail, is facing more than 170 accusations of corruption and law-breaking, ranging from diverting state funds to staying in his post past the national retirement age of 60. Last week, a court ordered Grameen Kayla, a nonprofit chaired by Yunus that provides affordable health services in rural areas, to pay more than 1 billion Bangladeshi takas, or $10.8 million, in alleged back taxes.

The raid on the Grameen complex “gives organizations within Bangladesh, whether NGOs or in the private sector, reason to worry about being perceived as insufficiently supportive of the government,” said Jonathan Morduch, a professor at New York University, and author of The Economics of Microfinance.

Blood feud

Morduch said the crackdown is targeted at Yunus himself, rather than a broader attack on microfinance and development strategies in other countries.

Allies of Yunus say Sheik Hasina wants to take over the Grameen business empire Yunus founded and use its income to shore up her own political position.

The accusations against the 2006 Peace Prize winner follow years nearly of attacks from the populist Sheik Hasina, daughter of Bangladesh’s independence leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Her government established an anti-corruption commission that observers say seems uniquely targeted at Mr. Yunus.

George and Amal Clooney’s Clooney Foundation for Justice has called the multiple charges against Yunus “politically motivated” and said his prosecution was “a tool of judicial harassment.” Yunus is free on bail until mid-April, while his attorneys appeal his convictions and continue to fight multiple trials on the other charges.

In 2011, Hasina accused Yunus of “sucking blood from the poor,” In 2022, she claimed that he’d blocked a World Bank loan for a new bridge just to spite her after her government told him he must retire.

“They emailed Hilary Clinton,” Hasina said in 2022, accusing Yunus and a colleague of blocking the loan. “On his last working day, without any board meeting, he blocked the funds to Padma bridge.”

“He should be plunged into the Padma River twice,” she said. “He should be just plunged in a bit and pulled out so he doesn’t die, and then pulled up onto the bridge. That perhaps will teach him a lesson.”

Sheik Hasina and her Awami League won re-election in January after police jailed at least 11,000 members of the opposition Bangladesh National League, which boycotted the vote, according to an Awami League official.

Since taking office in 2009, Sheikh Hasina has worked ruthlessly to maintain her party’s grip on power, the International Crisis Group said in a January report.

“Over the last decade, Hasina has established a firm grip on the country’s key institutions, including the bureaucracy, judiciary, security agencies and electoral authorities, filling them with loyalists. Her government has also persecuted opposition activists, civil society figures and journalists,” the ICG noted.

Revenue flows

At the end of January, 247 global leaders including 127 Nobel laureates wrote an open letter to Sheik Hasina urging her to end what they called a “travesty of justice,” and stop prosecuting—and persecuting—Yunus. In October, Amnesty International called on Bangladesh to end its “vendetta” against Yunus and “stop weaponizing labor laws” against him.

Allies of Yunus say the reasons for Sheik Hasina’s campaign against him are obvious: his poverty-fighting effort has made Yunus more popular than the prime minister, and the tens of millions of dollars in cash that Grameen companies generate, which is reinvested in other poverty-fighting programs or distributed to the companies’ worker-owners, is a lucrative pool of cash that could be diverted to strengthen Sheik Hasina’s own grip on power.

At the core of the Grameen network’s operation is the Grameen Bank (the name means rural or village in Bangla), and affiliated companies including Grameen Phone, a massively successful joint venture of Norway’s Telenord and Grameen Telecom that is the country’s largest telecom operator. Other ventures in the family include clothing manufacturers, energy supply companies and the Grameen kiosk, a stand providing online access to government services the group hopes to install in every village.

Yunus himself often serves as a director of these companies but has no ownership stake. Most are either worker-owned cooperatives or non-profits that direct revenues to other social projects, including hospitals, a nursing school and a string of local medical clinics.

Still, the bank remains one of the country’s most impressive institutions. Credited with sparking the microfinance revolution that transformed global anti-poverty strategies, Grameen Bank has lent nearly $37 billion, including more than 19 million loans to microenterprises, since its inception in the 1970s. Almost all of that has been paid back, according to the bank’s own figures. In an indication of how it has lifted women out of poverty, 10 million of the 10.45 million members of the Grameen bank are women.

That work has helped raise Bangladesh’s per capita income from $424 in 1980 to $1,784 in 2022, according to figures from the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank, and has propelled it to the middle ranks of the United Nations’ Human Development Index.

Saskia Bruysten, who has worked with Yunus for nearly two decades as a senior leader of Yunus Social Business, a German-based nonprofit that works to expand Grameen-type programs to other countries, says the dispute with Yunus is personal for Hasina.

“Yunus is a threat to her,” Bruysten told ImpactAlpha. “Grameen Bank, which Yunus doesn’t control, serves 9.8 million women every week with loans. That’s 40 million voters or more. That’s a very powerful tool,” said Bruysten. “If she controls it, she can say, ‘Vote for me and I’ll lower the interest rate.’ ”

Taking over Grameen’s mobile phone stake would give Hasina or her government control of tens of millions of dollars in profits that could be used to benefit her party, said Bruysten. Right now, that money is plowed back into other social projects, including a recently opened hospital and series of medical clinics.

At the Munich Security Conference in Germany at the end of February, Bruysten said she approached Sheik Hasina in a corridor and asked her why her government continued to prosecute Yunus, and if they would allow an independent judicial review of his case, a long-standing demand of human rights groups.

“Literally, the moment I said ‘Grameen,’ her mood shifted from this cute little granny that she was on stage to this fierce fighter,” recalled Bruysten. “She was spewing, literally.”

After Bruysten walked away, she said, Hasina came up to her and said “You can have your independent review, and I’ll tell you one thing: You won’t be proud of him.”

Taking control

In the aftermath of last month’s armed takeover, Yunus said police refused to register a criminal case regarding the incident.

“They find no problems” with the occupation of the firms’ offices, he said. It’s not immediately clear if the self-proclaimed new managers are still in control of the companies or whether Grameen’s revenue has been diverted to new uses.

“Some people came and took control forcefully,” Yunus told journalists in Dhaka. “We’re in deep trouble. It’s a big disaster,” he added. “They are trying to run the companies according to their rules.”

Hasina’s administration began a series of investigations of Yunus after she was elected prime minister in 2008. Yunus’ announcement the previous year, that he would run for office, reportedly enraged Hasina, even as Yunus ultimately declined to form a party or run for office. But the two have been trading accusations ever since.

Yunus charged that the country’s politicians care only about money. Hasina called him a “bloodsucker” for allegedly strong-arming Grameen’s poor rural women borrowers into repaying their loans.

In 2011, Hasina’s administration fired Yunus as managing director of the bank, for failing to retire at age 60. Yunus was 70 at the time. Hasina, now 76, was herself already three years past the official retirement date. Two years later, he was tried for receiving money, including his Nobel Prize, without government permission.

In the interview last month, Yunus said he has never had political ambitions, recounting how, in the early 2000s, senior officials of the military regime then running Bangladesh pressured him to become the country’s prime minister. He refused.

“I said, ‘I am not the kind of material you’d like to see at the head of the government.’”