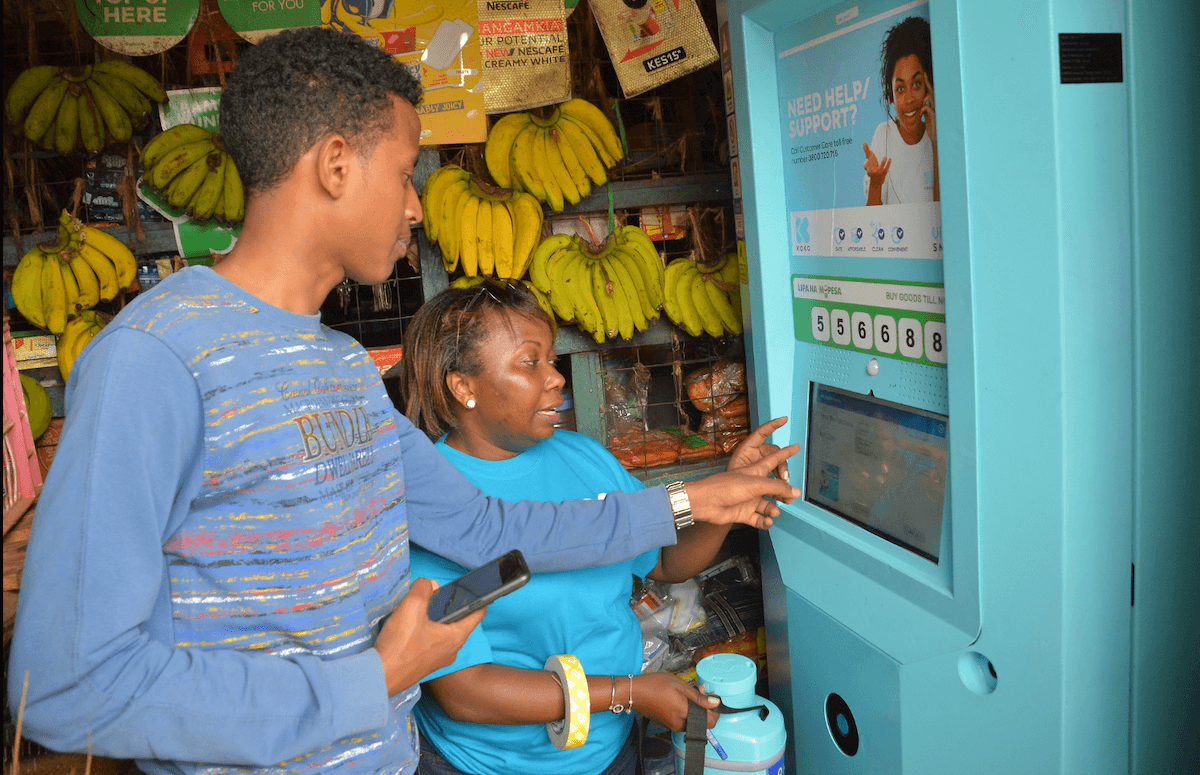

Nairobi’s slums are dotted with little aqua blue signs alerting residents to top-up points for cooking fuel. Many households don’t have electric stoves or installed gas lines; as with other daily essentials, they buy cooking fuel on an as-needed basis.

The price households pay for that fuel, sold by a company called Koko Fuel at those blue-branded top-up points, is lower than most other alternatives, thanks to Koko’s ability to tap into the voluntary and compliance carbon markets.

Koko is one of a number of clean cooking providers in Africa leveraging carbon credits to deliver safer, cleaner and more affordable household cooking options to lower-income Africans.

“Effectively it’s a non-government energy subsidy,” explains Koko’s Greg Murray. “In America, in Europe, you get energy subsidies delivered by the government to switch from gas to electric. We’re doing that through the private markets – effectively by taxing foreign corporates for pollution and using that as a subsidy funding source to switch Africans to low-cost, clean energy.”

Companies like Koko and BURN Manufacturing in Kenya and Bboxx in Central Africa use credits calculated based on carbon emission and deforestation avoidance to cut the cost of their cooking technologies and fuels for low-income Africans, passing benefits directly to their customers. Leveraging the carbon markets is now such a key part of clean cooking companies’ strategy that they issued an estimated 15% of total credits sold into the voluntary markets.

The strategy isn’t without flaws or criticism. Insiders have suggested that the field is now dependent on carbon credit sales to make the economics of their business models work, which is straining companies in the current low-price environment. One recent study called out rampant “over-crediting” in the field.

Industry experts acknowledge that over-estimation is highly likely, but argue that focusing solely on carbon accounting misses the point.

“We need to relook at this entire climate market through the lens of buyers’ net-zero commitment strategies,” argues Ashish Kumar, an impact investor and carbon market strategy expert and former climate and innovation lead at the Shell Foundation. The bigger issue is whether buyers are working to meaningfully reduce their holistic carbon footprints, rather than solely relying on the offsets for becoming “green,” he says.

“Offsets should only be considered once the strategies to avoid, reduce and substitute emissions have been implemented. Buyers are maturing in this portfolio approach, and this will help refine the role that offsets can play in climate market mechanisms going forward,” Kumar adds.

Focus on fuel

Nearly two billion people worldwide—a quarter of the world’s population—rely on crude, dirty fuels like firewood, charcoal and kerosene for home cooking and heating. In forest-dense countries like Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, charcoal and firewood production is a leading cause of deforestation. Smoke exposure from burning such fuels contributes to more than three million premature deaths each year, primarily women and children.

It’s the latter problem that most clean cooking companies have sought to address through new, affordable cooking technologies. Early versions of “clean cookstoves” from producers like BioLite and BURN Manufacturing didn’t seek to overhaul household behaviors; rather, they aimed to burn biomass fuel sources better so people breathed less polluted air and less particulate matter got into the atmosphere.

Many such models struggled to gain traction both with investors and with users, who often found designs too unreliable or unfamiliar to fully adopt. So-called “efficient stoves” were also found to have “no discernible effect” on smoke exposure long-term. Few models meet the World Health Organization’s guidelines for indoor emissions.

Better-burning cookstoves have by now largely fallen out of favor in the clean cooking community. Companies like BioLite and BURN continue to sell versions of their improved charcoal and wood-burning stoves, but are pushing other products like solar energy (BioLite) and electric and LPG stoves (BURN). The industry organizing body, the Clean Cooking Alliance, dropped the word “cookstove” from its name in 2018 to reflect a shift in focus to better fuel sources, which “accounts for the majority of consumer spending when it comes to cooking.” Cooking technologies using ethanol, biogas or LPG, for liquefied petroleum gas, more reliably adhere to WHO air pollution standards.

Advancing fossil fuels?

Encouraging adoption of such fuel sources, especially LPG, seems to run counter to the global climate agenda and phase-out of fossil fuels. But the clean cooking field’s coalescence around LPG is mostly about eliminating charcoal.

“It’s a redefinition of the problem,” explains Mansoor Hamayun of off-grid energy company Bboxx. “The enemy is charcoal.”

Hamayun has provocatively described LPG in Africa as more “carbon-positive” than solar power. “Bboxx can earn more carbon credits from switching families from charcoal to pay-as-you-go LPG for cooking than from switching them from kerosene lamps to pay-as-you-go solar home systems,” Hamayun wrote last year of the company’s decision to enter the LPG-cooking market.

“It was also my own great personal surprise that we ended up selecting LPG as the solution,” Hamayun tells ImpactAlpha. “It’s quite an unusual choice for a solar company to expand into LPG, but we did the math.”

The carbon math, because of charcoal’s contribution to deforestation and toxic emissions. But also, the availability math: LPG is more widely accessible in Africa than biogas, biofuels and electricity.

The cleanest option—solar and battery-powered cooking technologies—remain “prohibitively expensive” for widespread adoption in Africa, says Hamayun.

“African families will make rational economic decisions about their household needs like anyone else – based on cost. They will not willingly switch to a more expensive fuel for cooking, especially when they may already be lacking access to essential products and services,” he wrote.

Pollution tax

Helping to phase out charcoal and firewood use is clean cooking companies’ pathway into the global carbon markets. Companies calculate roughly how much charcoal and firewood their products would replace over their lifetimes and then issue verified carbon credits based on those estimations.

Bboxx, now headquartered in Kigali, began piloting its clean cooking carbon markets strategy in the DRC in 2020 with support from USAID. In December, it announced a $100 million partnership with Kuwait to ramp up clean cooking and energy access in 11 African markets. Kuwait is actively investing in carbon credits in Africa as part of the oil state’s 2060 net-zero goal.

Nairobi-based BURN Manufacturing was among the earliest clean cooking players in the carbon markets, selling its first credits almost a decade ago. More than four million credits sold to individual and corporate buyers have enabled the cookstove maker to sell over four million of its devices in Africa.

The company also in October rolled out a $10 million green bond, among the first in Africa’s clean cooking sector, to build a manufacturing facility in Nigeria.

In the clean cooking sector broadly, most credits are going into the voluntary markets, where companies buy credits to off-set their own emissions. But imperfect methods of accounting, verification and traceability of credits in the voluntary markets risk discrediting issuers. (See: South Pole.)

Koko is tapping the more rigorous Article 6 compliance markets, which were set forth under the Paris Climate Agreement to allow bilateral trading between companies in one country to another. The investment agreements it undertakes with host countries provide legally binding guarantees for the credit export permits required to access these markets.

In Rwanda, Koko is laying the groundwork to bring in foreign carbon capital to support the President’s ambition to phase out charcoal and firewood. The company last year signed an investment agreement with Rwanda wherein it committed to building a $25 million country-wide “energy utility” for its ethanol cook fuel. The capital expenditure is almost 20 times less than what the government had calculated for LPG infrastructure, Murray says.

“Liquid fuels have an infrastructure cost advantage. More than $100 billion in infrastructure exists across low-income tropical forest nations—it’s been built for diesel, petrol and kerosene,” Murray explains. Kerosene especially is “in every village in Africa,” he says.

That infrastructure is usable on a “drop-in” basis for bioethanol, he adds.

In Kenya, Koko is successfully leveraging fuel infrastructure to the point that its molasses-based ethanol can beat even LPG prices, the next cheapest fuel source. It partners with Shell-branded petrol stations to store its ethanol in 50,000-liter tanks underground, then dispatches a fleet of “micro tankers” to deliver the fuel to its more than 2,700 top-up points at mom and pop shops throughout Kenya’s urban slums.

The company is making the case to replicate the model in Rwanda provided the government eases up on technology import duties and sales tax on customers.

“We’re saying we don’t need any subsidies from Treasury, unlike the LPG industry,” Murray explains. “Instead, we’re going to “tax” foreign corporations for their pollution through the carbon markets, and bring that revenue into Rwanda as an import of hard currency. That goes directly to citizens’ wallets in the form of low-cost clean energy.”

Climate justice

Such models for leveraging carbon credits effectively act as a form of climate reparations for climate vulnerable countries and populations that are suffering the impacts of climate change despite contributing little to it.

For the sake of the clean cooking field’s legitimacy, accounting and verification practices are improving.

“It will get easier as cooking technologies become more digitally-enabled with sensing devices and software,” says Dan Waldron of Acumen, an investor in BURN. Waldron has watched BURN expand its carbon market channels in recent years, which include designing projects directly for large institutional buyers and selling credits to individuals through its website.

He says he’s excited about how BURN and other clean cooking companies are using the carbon markets to deliver social benefits, like improved financial security from families saving on daily essentials, and improved health from breathing cleaner air. These can’t yet be assessed or monetized in the same way as environmental benefits.

“Long term, buyers have to reduce their carbon footprints to get to anything like net zero, so there are limits to linking poverty funding to carbon credits,” he says. “There are plenty of other ways we can design credits that support poverty alleviation, so in the short-term, co-benefits are a good option.”

“Eventually we’ll come out to a place that’s imperfect,” he adds, “but which will still help a lot more people get access to products that make a big difference.”