ImpactAlpha, Dec. 13 – We were on our way to see family in South Carolina this summer, so we flew into Charlotte a few days early, picked up a cousin for company and headed to the coast for a mini-roadtrip in a pandemic.

We’re an odd family, or maybe it’s just me. The Sea Islands had pulled at me ever since college, when I had listened to the stories of my provost, Herman Blake, who had worked with the area’s Gullah Geechee island communities (for a window into the culture now, check out this episode of the Netflix food series, High on the Hog).

But I was largely ignorant about the Lowcountry as we crossed the causeways, passed the Marine Corps bootcamp at Parris Island and found our Airbnb off the sleepy main street in the historic town of Port Royal.

All year, ImpactAlpha had been exploring the contours of the Reconstruction as a historical antecedent to our own period of social ferment, division and systemic change. In dozens of podcasts and on the beat of racial-justice entrepreneurs and investors, we had reinterpreted the period after the Civil War as an inspiring, if ultimately tragic, experiment in multiracial democracy and prosperity.

Now, almost by accident, we had landed at the site of the original laboratory for America’s reset after the Civil War, the epicenter of the social innovation known as Reconstruction. With all of its conflicts and contradictions, the Port Royal Experiment served as a ‘rehearsal for Reconstruction,’ three years before the end of the Civil War.

Unfulfilled promises

I learned that in November 1861, only seven months after the battle of Fort Sumter, the Union navy had recaptured Port Royal Sound and made it a linchpin of its Atlantic blockade. White planters and residents fled behind Confederate lines. The 10,000 Black residents stayed, and celebrated their sudden liberation and control of the cotton and rice fields and plantation houses.

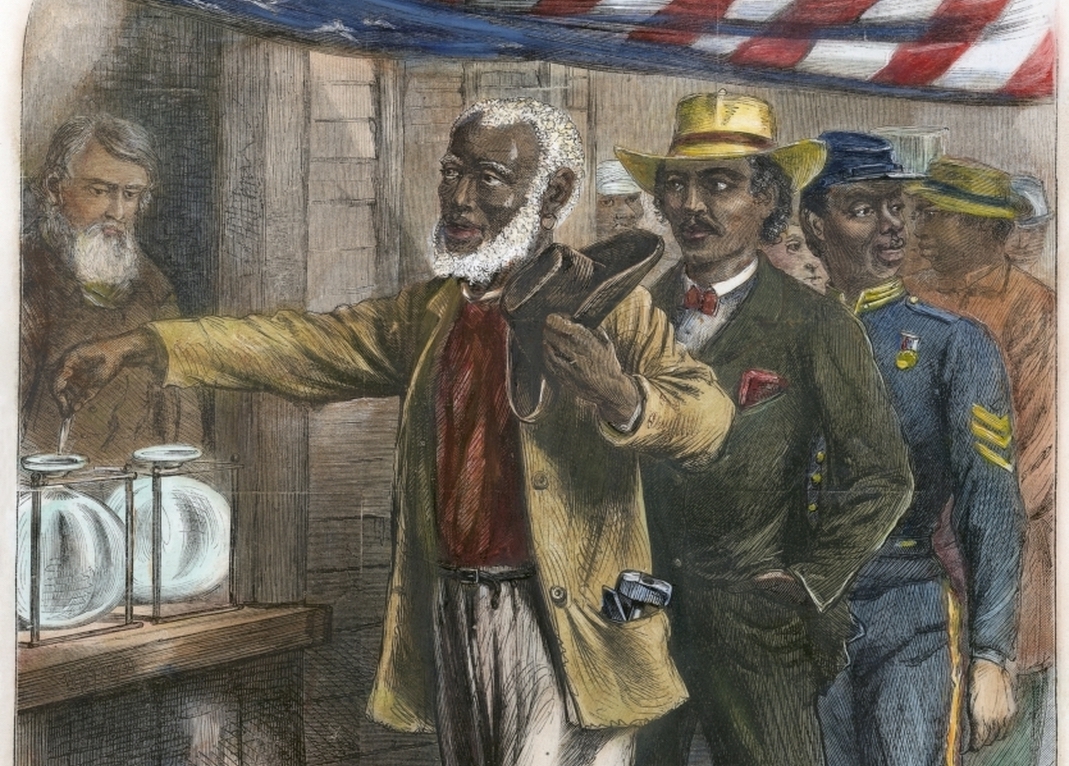

‘The Port Royal Experiment,’ as historians describe it, was an early demonstration of the self-organizing capacities of Black communities and individuals. The military occupation morphed into a testbed for free labor and education. How would work and land and governance be organized in a post-war South?

The fiercest contests were, and still are, over land. Formerly enslaved people were able to purchase only small plots and a small portion of the confiscated plantations – an early installment on the also unfulfilled promise of ‘40 acres and a mule.’ But by 1870, about 1,200 freedmen and women owned land in Beaufort County, the most in the entire South.

The place to start was Penn Center on nearby St. Helena Island, the heart of Gullah culture. As Penn School, it was one of the first schools for formerly enslaved people, which operated through the 1950s. The site later served as a retreat for the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who is said to have written his 1963 March on Washington speech there.

“We are on hallowed ground,” the gracious Miss Gardenia Simmons-White, 87 years old, a guide at Penn Center, told me for a July episode of ImpactAlpha’s Impact Briefing podcast.

The historic and ongoing legacy of Black land loss on islands like Hilton Head and St. Helena belies the paucity and fragility of the earlier redistribution.

But if the story of white speculators and developers taking advantage of Black farmers is depressingly typical, the story of Black prosperity and resilience in the Lowcountry is refreshingly different.

So is the extent to which the region makes The Reconstruction a center of the tourist trade. Beaufort, S.C., the seat of a county that went for Trump over Biden by about 10 points in 2020, anchors its historic district around The Reconstruction Era National Historic Park and the region’s multi-racial legacy of social experimentation.

The local hero is the remarkable Robert Smalls, whose exploits in spiriting the Confederate steamship, the Planter, and 17 escapees out of Charleston harbor to Union lines is the subject of the upcoming Amazon movie, Steal Away.

The oversimplistic reason for the celebration of the Port Royal experiment is that it worked, making the Port Royal Experiment a vehicle for the retelling of the Reconstruction story, centered around Black capacity and the kind of local prosperity even downtown merchants could get behind.

Rather than a failure that begot the Jim Crow backlash, in places like Beaufort, the Reconstruction was an egalitarian success, albeit one that later was crushed by a revanchist white supremacist power structure. A revolution, with failed execution, in the words of playwright Gene Bruskin, creator of The Moment Was Now, a musical set in 1869 Baltimore. Bruskin calls Reconstruction “the moment when America almost did the right thing.”

New social contract

For decades, the story of the Reconstruction era, replete with denunciations of “carpetbaggers and scalawags,” was distorted by the perspectives of its opponents. That opposition was in large part a result not of the failures of Reconstruction, but of its success.

The decade-long experiment in multiracial democracy and inclusive prosperity spurred small-town vitality and the flourishing of Black businesses and professionals across the South that persisted for decades. Black political power and Main Street prosperity was attacked in a bloody coup in Wilmington, N.C. in 1898, in the destruction of “Black Wall Street” in Tulsa, Okla. in 1921 and in countless other acts of repression and violence.

The truism that history is written by the winners is demonstrated by the durability of the myth of the Redeemers, the white Southerners who fought Reconstruction. That biased version found academic respectability in what came to be known as the Dunning School, and popular appeal in the film Birth of a Nation, which glorified the Ku Klux Klan.

The revision of that mythical version started with W.E.B. DuBois’ magisterial Black Reconstruction, first published in 1935. It has been carried forward by historian Eric Foner and others, who have offered more honest appraisals of the remarkable economic and political agency of newly free Black citizens.

“Changing a regime based on slavery to one based on racial equality, that was a pretty big job to do,” Foner says. “The tragedy of Reconstruction is that the commitment to enforce it waned much too soon.”

Even supporters of Reconstruction mostly remember the white supremacist backlash that ushered in decades of Jim Crow.

But Jim Crow was a function of the defeat of Reconstruction. That makes any lessons for how a new mobilization for multi-racial democracy and prosperity can prevail over the inevitable and ongoing backlash particularly salient and welcome.

A resolution pending in Congress calls for “a third Reconstruction to build an equitable, thriving and resilient economy from the bottom up.” But it will take not just the whole of government, but the whole of America to close the racial wealth gap and fulfill long-standing promises of economic justice and shared prosperity.

In the sweep of history, the social reaction at the front edge of an economic dislocation can flip into social renewal as new capacities unleash growth and prosperity. In our time, such an ‘awakening‘ could harness the possibilities of a digital, renewable, distributed and connected world to a shared prosperity and broad uplift unlike anything the world has ever seen.

The proactive vision of economic liberation for all figures to be a mega-trend bigger than climate or even tech.

If it is not defeated.

Sesquicentennial

The first Reconstruction came only after a civil war. That makes today’s efforts to bridge the racial wealth gap and rebuild America as much preventative as restorative. Today’s multi-movement mobilization for multiracial democracy and prosperity is an anti-war strategy.

As it was 150 years ago, so too now are we writing a new social contract in a time of dislocation and disruption. Then: a devastating Civil War. Now: a devastating pandemic and a racial justice reckoning. Then: four million citizens newly freed. Now: 10 million undocumented immigrants. Then: railroads, factories and the industrial revolution. Now: environmental collapse and the digital revolution. Then: Manifest Destiny. Now: the net-zero transition.

Then: the implementation of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments. Now: Build Back Better, the For the People Act, and the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act.

As it happens, the pivotal events of The Reconstruction took place in the 1870s, making the 2020s a parade of 150th anniversaries. This year, for example, is the sesquicentennial of the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, signed by President Ulysses S. Grant to add enforcement to the 15th Amendment’s right to vote and protect newly freed citizens from racist vigilantes.

In a quirk of history, the conflicts over voting rights in that period saw Democrats actively suppressing Black voters to prevent Republicans from winning or retaining governorships as well as seats in statehouses and Congress.

At the end of the war, South Carolina’s Black population was more than 400,000, compared to only 275,000 whites. Klan violence was so widespread that Grant declared nine South Carolina counties to be in rebellion and suspended habeas corpus.

The ongoing sesquicentennial leads inevitably to the 150th anniversary of the previously most disputed election, in 1876 – when Congress decided the outcome – in favor of the loser of the popular vote. The dealmaking that settled the contest between Democrat Samuel Tilden and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes effectively ended Reconstruction, though pockets of multiracial prosperity survived for decades.

In the thumbnail history of that election, Eastern bankers in the party of Lincoln sold out multiracial democracy to make peace with white supremacists. Alignments have flipped but the anchors of that accomodation drag our politics down to this day.

Back in Beaufort, we got a glimpse of an alternative history. The war hero Robert Smalls persisted through repeated efforts at disenfranchisement. He served in South Carolina’s General Assembly from 1868 to 1874 and then was elected the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served, with a notable gap, through 1887.

On our last night in in town, we took a guided “ghost tour” among Beaufort’s gothic mansions and cemeteries. We learned that Robert Smalls had purchased the McKee house where he had grown up enslaved. Then Smalls took in his former enslaver, Jane McKee, left destitute after the war, and welcomed her in the house until her death.