‘Tis the season for our lookaheads to 2022 and, thanks to ImpactAlpha subscribers, we are able to make the roundups freely available. So give the gift of a link to ImpactAlpha’s industry-leading coverage of climate finance, impact in emerging markets, The Reconstruction and catalytic capital. You can find the whole set on our Looking Ahead to 2022 landing page.

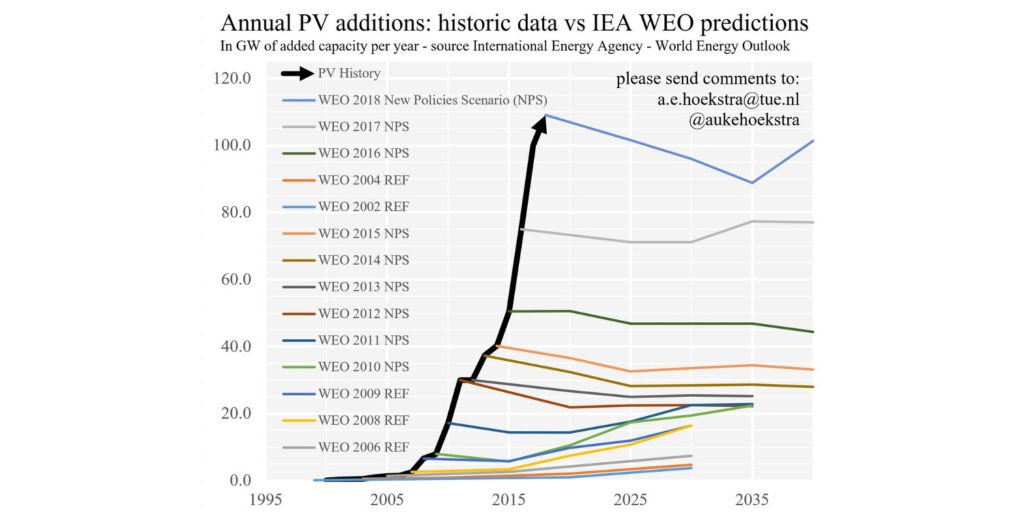

ImpactAlpha, Dec. 21 – It’s an optimist’s favorite: The chart of solar energy capacity shows that for two decades at least, actual installations have repeatedly outpaced even the best-case forecasts of global energy experts. (In 2012, for example, the International Energy Agency said global solar energy production might reach 550 terawatt-hours by 2030; actual generation passed that target in 2018.)

That’s only one of the climate solutions that have already reached the proverbial tipping point on the way to mainstream adoption.

For pessimists: the pace of climate change also is exceeding scientists’ worst-case scenarios. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s stark report found the planet is warming even faster than scientists thought, prompting U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres to declare “code red for humanity.”

Other worrisome data points from 2021 include the 5% rebound in global carbon emissions, which canceled out the decreases notched in 2020 amid COVID-related shutdowns. Coal power generation is set to reach a record high this year. And negotiators at COP26 postponed until next year’s climate summit in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, firm new targets for emissions reduction.

To reach net-zero by 2050, we need compounding emissions reductions of 7% – every year. Advocates have long known that climate solutions have to ‘go exponential’ to have any chance of averting the worst of the climate catastrophe. Investments in the low-carbon transition likely topped $1 trillion this year for the first time. But even the accelerating progress may not be fast enough.

Can climate action double, double and double again (and again) before the climate itself reaches an irreversible tipping point? There’s still an outside chance to muddle through, by aligning policy and capital with a wholesale mobilization of talent and will for exponential progress. Some of the signals ImpactAlpha will be watching for in 2022:

Bigger funds, bigger deals

Billion-dollar climate funds used to make headlines. Now $1 billion is table stakes. Investors including TPG, Brookfield Renewable Energy and BlackRock this year have raised multi-billion dollar climate-focused funds. Brookfield, behind vice chair Mark Carney, is said to be targeting a $15 billion fund. Generation Investment Management launched Just Climate to “create climate impact at scale.”

The mega funds are hunting for mega opportunities. Climate tech deal sizes swelled to an average $96 million in the first half of 2021, up from $27 million in the same period a year ago, according to PwC.

Among the year’s blockbuster deals: TPG Rise Climate and ADQ injected $1 billion into a new Tata Motors subsidiary that aims to accelerate India’s electric vehicle adoption. Sustainable battery recycling company Redwood Materials got a $777 million infusion in July. BlackRock invested as much as $500 million in Munich-based Ionity’s recent $700 million round to expand its EV charging network. And Commonwealth Fusion Systems raked in an eye-popping $1.8 billion to commercialize fusion energy.

Venture capitalists made 738 investments in climate tech totaling almost $31 billion through the third quarter of 2021, already more that 50% above last year’s total of $20.7 billion, according to Pitchbook.

The pace of fundraising has quickened, too. Generate raised two billion-dollar funds this year for green infrastructure. Tech investor Chris Sacca traded software dealmaking for climate tech this year, first making bets with his own funds and then raising $800 million from outside investors “in just a few days” and now eyeing additional funds for carbon capture and fusion.

The question now: where to invest all that powder? Electric vehicles and battery tech were 2021’s big sectors. In the year ahead, look for investors to home in on emerging solutions for hard-to-decarbonize sectors like steel, cement and aviation; unsexy green infrastructure such as waste-to-energy systems; and carbon removal, fusion and other moonshot technologies that will be needed to achieve net-zero by mid-century.

Catalytic capital is needed to de-risk and accelerate cost curves for climate-critical technologies. Some of the more ambitious climate solutions, such as direct air capture and sustainable jet fuel, are unproven and capital-intensive.

The returns are finally justifying the risks. Look for more ambitious deals that can create tangible climate impact at scale. As BlackRock’s Larry Fink declared, “The next 1,000 unicorns will be businesses developing green hydrogen, green agriculture, green steel and green cement.”

Go deeper:

- “TPG Rise ($5.4 billion) and Brookfield ($7 billion) raise the stakes for climate funds”

- “Deploying catalytic capital to bridge financing gaps for climate action”

- “Chris Sacca: ‘Cheaper, better, faster, stronger, simpler and just plain cooler’”

Spinning off ‘ReNewCos’

From transportation to energy, leaders in the low-carbon transition are pulling away from the laggards – even within the same company. Fossil fuel-era icons are being pushed to split their sustainable growth businesses off from their carbon-intensive legacy operations. Call them “ReNewCos.”

Hedge fund Third Point is pushing Shell to split in two. The Italian oil major Eni is spinning off its renewable energy, electric-vehicle charging and retail businesses into a separately traded company, Plentitude. The latest: Harley Davidson, which is spinning out its electric motorcycle division as LiveWire and taking it public via a SPAC.

The notion is that the ReNewCos can reap the rich valuations and easier access to capital enjoyed by clean energy providers and electric vehicle makers. The OldCos can be milked for profits while they last.

“The risk and return is totally different for the new business than the old business,” says UC San Diego’s David Victor, a professor of innovation and public policy. “The more the new businesses thrive, and the old businesses die, the more they must be managed distinctly.”

Go deeper: “Accelerating net-zero transition pushes incumbents to spin off green ‘ReNewCo’s’”

Carbon at $100 a ton

Carbon markets are booming. The European Union trading system, the oldest and most established regulated carbon market, started the year at €30. By December, it had nearly tripled to €81. Carbon prices in California’s market have risen nearly 60% in 2021. China’s national market, the world’s largest, launched this year – as did a raft of ETFs and hedge funds to track and bet on a rising carbon price.

The creation of a global carbon market remains elusive. But there is finally a price on carbon, or rather, multiple prices across the patchwork of policy “compliance” markets and increasingly active voluntary markets. The surge in voluntary markets, used mainly by corporations to offset their emissions while they figure out how to reduce them, was driven by net-zero pledges by countries and companies and a scramble by emitters and speculators looking to lock in carbon credits at low prices.

Carbon markets are still maturing. Lax standards have led to charges of greenwashing (see: Greta Thunburg at COP26). And carbon offsets, of course, are no substitute for absolute emission reductions. But the increasing demand and rising prices for such credits is benefiting projects that can sequester carbon in soil, forests or wetlands, as well as tech solutions that can suck carbon out of the air. Intermediaries are emerging to coordinate the action.

The LEAF Coalition, run by the non-profit intermediary Emergent and backed by the governments of Norway, the U.K, and the U.S., is bringing together forest countries that can sequester carbon and corporate buyers such as Delta Airlines and Unilever. Carbon removal startups such as Climeworks and Charm Industrial are commanding more than $600 a ton for carbon removed from the atmosphere.

Why does it matter? Conservation projects and mitigation investments that currently do not pencil out will look attractive when prices for averting a ton of carbon reach $100 or more. Farmers can generate added revenue by sequestering soil carbon with regenerative farming practices. Conversely, fossil fuel assets and projects may become stranded when the price of carbon is factored in.

Averting methane and other short-lived climate pollutants is even more valuable. At COP26, more than 100 countries pledged to reduce emissions of methane by at least 30% from 2020 levels by 2030. A ton of methane has at least 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide in its first 20 years. California’s Low-Carbon Fuel Standards and federal renewable fuel standards are providing significant revenues for methane-reduction projects. “We may sell our methane for $5 and our environmental credits associated with that could be $80,” says Dave Chen of Equilibrium Capital, which builds and operates dairy-waste biogas plants.

What we’re looking for: Rising prices as demand for carbon credits and allowances – some of it driven by regulation – exceeds the supply. Standards to make carbon markets interoperable and carbon credits fungible. That means distinctions between high-quality carbon credits that actually remove carbon from the atmosphere and keep it out; and lower-quality credits for carbon emissions averted. Still in the realm of possibility around the world: carbon taxes.

Go deeper:

- “That feeling when investors realize carbon is going to $100 a ton sooner than they expected”

- “Farmers harvest ‘soil carbon’ to meet rising corporate demand for emission offsets”

- “Forget crypto: Here’s how to play the rising price of carbon (podcast)”

Climate action requires climate justice

From the streets of the Bronx to rural Kenya, communities of color are bearing the brunt of climate change. They are also uniquely positioned to identify and scale solutions.

In the U.S. entrepreneurs like BlocPower’s Donnel Baird, ChargerHelp’s Evette Ellis and Kameale Terry, COI Energy’s SaLisa Berrien and other homegrown startups are building solutions to climate-related challenges faced by underserved communities. Across the globe, local leaders from under-represented communities are speaking out and taking action, including Uganda’s Vanessa Nakate, whose Rise up Climate Movement has campaigned to protect Congo’s rainforest and installed rooftop solar on schools.

Climate-resilient infrastructure and low-carbon retrofits offer a generational opportunity for health and wealth. Investors and global leaders are starting to pay attention.

“We need to have founders and investors who have relationships with the communities that will have the greatest impact of climate change,” says Include Venture’s Taj Eldridge. With VC Include’s Bahiyah Robinson, Eldridge is spearheading a Climate Justice Initiative to recruit and support underrepresented and diverse climate fund managers in the U.S. and Europe.

In Kenya, Elizabeth Wathuti’s Green Generation Initiative works with young people to plant food-giving trees. At COP26 in Glasgow last month, the 26-year old implored world leaders to open their hearts to Africans increasingly subject to devastating drought, heatwaves, wildfires and floods from climate changes they did not cause. “If you allow yourself to feel it,” she said, “the heartbreak and the injustice is hard to bear.”

Go deeper:

- “Solving for climate justice is giving these Black investors an edge in the green economy”

- “How climate-tech investments can create health and wealth in Black and Brown communities”

- “Call No. 32: Black tech, green solutions for the planet and the people”

Investors flex their muscles (even more)

It was the proxy vote heard ‘round the world. In May, tiny Engine No. 1 secured the votes of a majority of shareholders of ExxonMobil to vote three insurgent candidates onto the oil giant’s board.

The upset capped a season of stunning climate wins by shareholders, who delivered stinging rebukes to climate laggards such as Chevron and ConocoPhillips, while a judge in the Netherlands ordered Royal Dutch Shell to cut its greenhouse gas emissions. Emboldened shareholders are readying more ambitious proposals for the 2022 season, asking companies to set science-based targets, create transition plans and align their lobbying with global climate goals.

And they are increasingly taking the fight to company directors, voting against re-election of board members wed to business-as-usual.

“It’s kind of like the shackles are off and let’s swing for the fences on some of these proposals,” says Engine No. 1’s Michael O’Leary.

Go deeper: