ImpactAlpha, Feb. 2 – Ross Baird has made a career of plugging capital gaps for promising ideas in their earliest stages.

Before “accelerator” and “angel investor” and “seed stage” were household terms, Baird built Village Capital to fund early stage startups outside of Silicon Valley.

With Blueprint Local, Baird is marshaling local investors, long-term investment horizons and Opportunity Zone tax breaks to capitalize early-stage real estate development projects that otherwise would not have been financed. The projects aim to make housing more attainable and give local businesses a place to grow in Baltimore, Charlotte, Atlanta, Huntsville, Austin and other “Zoom towns.”

“In real estate, if you have a promising idea, it’s very, very difficult to raise money to acquire a piece of land or acquire an abandoned building and get the seed funding to do the pre-development work,” Baird told ImpactAlpha. “The idea of a seed stage venture fund in real estate doesn’t by and large exist. That’s a very specific gap that we have filled for a few projects successfully.”

Migration to second- and third-tier cities in the Southeast and Sunbelt, accelerated by COVID-19, has put pressure on the region’s already short supply of housing and weak infrastructure, and exacerbated already high wealth inequality. “Growth tailwinds. Historic disparities,” says Baird. “There’s a lot of opportunity.”

In a Q&A with ImpactAlpha, Baird shares why private equity investors don’t have the stomach for community investing and what to make of the impact of Opportunity Zones.

Blueprint has made 15 investments in nine cities since 2018 and manages $150 million across a series of funds and special purpose vehicles. Early projects include the revival of the historic transportation hub of Penn Station in Baltimore. The Current, a block-sized development in the distressed Manchester neighborhood of Richmond, will have over 200 units of mixed-income workforce housing, commercial space for homegrown startups and a food incubator for local food entrepreneurs.

Baird says neither project could have been financed without Opportunity Zone incentives. “On the local level, the reaction to Opportunity Zones in general and the projects that we’ve been involved in are nearly all positive,” he says. “ I think the additionality of Opportunity Zones is real.”

ImpactAlpha: You launched Blueprint Local four years ago. Bring us up to speed.

Ross Baird: We have a series of affiliated funds and special purpose vehicles. Collectively, our related entities are approaching $150 million in assets under management. Blueprint now has 15 investments in nine cities across the southeast and Texas.

We started in 2018 and it really grew out of a long series of engagements in my time running Village Capital in distressed communities in the US. Access Ventures, an impact investment firm based in Louisville, had done a lot of real estate investing in Louisville that was very intentional. Access Ventures was a founding partner of Blueprint Local.

The idea behind Blueprint Local is something that I and many others had been thinking about – a place-placed strategy for investing in communities. Separately, through Economic Innovation Group, the think tank, I got involved in the advocacy for the Opportunity Zone legislation. Village Capital had been investing in a large number of companies that ended up being in Opportunity Zones. I had originally approached the legislation with an eye towards my work at Village Capital but when the Opportunity Zone legislation passed, the Blueprint Local idea was something that a number of us had been doing for a while. Tax strategy is never a reason to do or not do something, and I think the investment thesis behind Blueprint is fundamentally strong and would be without a tax strategy. But it felt like a good time to take the new strategy to market with a lot of focus on Opportunity Zone investing.

ImpactAlpha: Early on, some of Blueprint’s funds were multi-asset class and focused on specific cities. How did investors respond?

Baird: Very early on we started with an idea of a place-based, multi-asset class fund. The original idea of Blueprint, we were going to do a Blueprint fund for X city to invest in both real estate and businesses that have a positive impact in that community. I thought it was a great idea. We found very few limited partner takers for that. One of the things anybody in the impact investment world needs to think about is investors think in categories and asset classes, and trying to build strategies that require too much of a leap of faith for investors, early on, it’s just very difficult.

We pivoted the model slightly, to where now each year we launch one diversified fund. We are very focused on the southeast and Texas, so we invest regionally. But we’re not tied to a particular city.

We thought that investors would say, “Oh, I really am excited about Baltimore. I really am excited about Atlanta.” We found that for those types of opportunities, investors want to go directly in at the asset level versus go through a fund, and so our diversified fund has been of interest to people who want diversification and are interested in regional diversification. For the investor who really wants to invest in Baltimore or Atlanta, for some of our larger investments we’ve opened up special purpose vehicles for direct investment opportunities where investors can go directly into the deal.

We originally thought the fund would have both real estate and operating businesses. For a number of reasons that ended up not being the strategy. The funds that we manage now are all real estate funds.

We are interested in working on operating businesses. We announced last year a partnership with the Economic Development Administration at the Department of Commerce and six pilot cities to try and stand up operating business funds. We have pilots, or more like research and development work, going in with six partners across the country to work on operating business funds. In the Opportunity Zone world operating business investment has taken more time and it’s been more challenging.

ImpactAlpha: Say more about some of your investments.

Baird: Blueprint’s investments have fallen into a few buckets. One, redevelopment of civic landmarks. So Penn Station, Baltimore is probably the most prominent example. We have a couple of other examples of where we’ve been able to engage in historic, strategic buildings that have had great history and are currently abandoned or distressed that can be redeveloped for the betterment of the city. That’s been a big focus.

Bucket two, mixed use. We use the phrase ‘placemaking.’ Businesses and housing and public amenities all working together. Investing with the whole community approach. We have made an investment in a project in Richmond called The Current that is a whole city block in the Manchester neighborhood of Richmond. It’s historically manufacturing. It’s very distressed currently. We have over 200 units of mixed-income workforce housing. We have a commercial site where a company called Koalafi, which is one of the fastest growing startups in the region, has just announced their headquarters. Then on the ground floor we’ve partnered with a local food incubator called Hatch, which provides employment and entrepreneurship opportunities for startup food entrepreneurs. For people that might have a food truck and want to open your first restaurant or cater out of their kitchen and want to get a storefront.

ImpactAlpha: A few years in, how are you thinking about Opportunity Zones? Is the program helping to drive capital into projects that are positive for distressed communities?

Baird: There have been a couple of New York Times stories that are negative at a national level. They’ve dominated the press, unfortunately. I would say on the local level, the reaction to Opportunity Zones in general and the projects that we’ve been involved in are nearly all positive. Taking the Richmond example, co-locating workforce housing, a food incubator, and a tent pole for a homegrown local business, the degree of difficulty of doing that is extremely high. I would say “but for” Opportunity Zones, that project, and Penn Station, and many others would have had a much harder time raising capital. I think the additionality of Opportunity Zones is real. Very few of our projects would, in my opinion, have been capitalized as they have without Opportunity Zones.

Part of that is the tax advantage for sure. The most meaningful benefit of Opportunity Zones is the 10-year time horizon. Bill Gates has a line where he says, “You overestimate what you can do in a year and underestimate what you can do in 10 years.” Community investment is really hard work and it takes years for things to come together. If you talk about a project that could be successful, the average private equity investor wants their money back in three years. They want to buy a building where wealthy people are already living and flip it and extract money in three years. We have projects that we believe will be financially successful but they’re going to take more time to come together and the Opportunity Zone program, I think the biggest benefit is it has incentivized investors to take a more long term view. That’s helped financially because we’re pursuing projects that I think will have more lasting value and will ultimately be more financially successful for investors but also hopefully impactful.

From an environmental sustainability view point, environmentally sustainable buildings will be worth more 10 years from now than they are today. So things like building materials and electric vehicle chargers. If you think about where the world is going and you make decisions with a 10-year horizon that you may not make with a three-year horizon. I’ve just seen so many case studies of where this program has helped investors with a long-term view build successful projects.

ImpactAlpha: How big is the “local” investing opportunity?

Baird: It’s really hard. One of my big takeaways on impact investing in general and my experience with Village Capital. I’m very, very proud of Village Capital and proud of Allie and the team’s leadership. You can be either sector- or stage-specific and broad, but you have to be extremely specific about the sector or stage that you’re doing. Or you can be narrow and deep. But you can’t as any one firm be all things to all people. Village Capital, for instance, is extremely specific about the kind of seed stage entrepreneur that we work with and then we’re geographically flexible. Blueprint in some ways is different. We see all kinds of different projects and all kinds of different shapes and sizes. We’ve decided to be very geographically focused and we’ve decided to be very ‘stage of development’ focused for our real estate investments.

One of the market gaps that I’ve observed is in the venture world: seed stage funding, startup funding, incubators, accelerators, all that, there wasn’t much 10 years ago now. Now there is an industry and community around seed funding. In real estate, if you have a promising idea, it’s very, very difficult to raise money to acquire a piece of land or acquire an abandoned building and get the seed funding to do the pre-development work. The idea of a seed stage venture fund in real estate doesn’t by and large exist. That’s a very specific gap that we have filled for a few projects successfully. We’re very state specific. There are only a handful of cities that we’re focused on. Within that stage and those cities, that gives us flexibility to look at different projects.

ImpactAlpha: That’s interesting, the connection between the startup ecosystem and the real estate ecosystem in terms of stage of development.

Baird: When Village Capital started, TechStars was around. Y Combinator was around. There were a few angel investors who were doing a lot individually but the idea of a seed stage fund, particularly with an impact focus was extremely rare. Now there are a lot more. That’s great for founders. I view the real estate funding landscape today very similar to the venture funding landscape in 2008, 2009, where there are a few large players and a lot of self-funded individuals. But not a lot of early stage capital for promising projects. And so for me, it’s a similar stage and strategy to what we built at Village Capital, but applied to real estate.

ImpactAlpha: What cities and projects are you excited about?

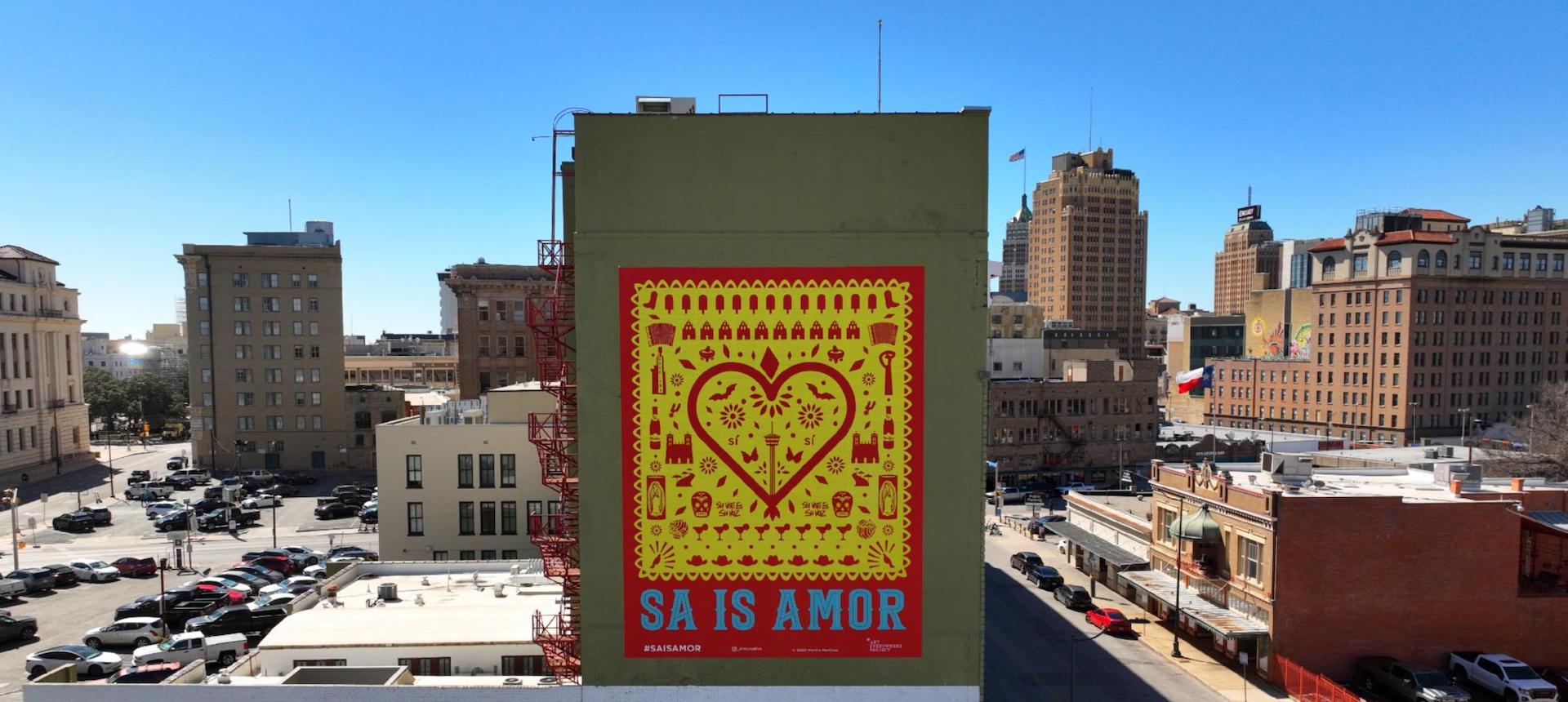

Baird: We use a phrase a lot: “Zoom towns.” Looking at Village Capital, these are areas that we were investing in before launching Blueprint. Village Capital is well-represented in places like Durham and Atlanta and Austin. There’s a significant population migration to second- and third-tier Southeastern, Sunbelt cities and it was happening pre-COVID. Think the Steve Case/Rise of the Rest movement. COVID really accelerated what was happening anyway. Cities like Charlotte, Atlanta, Huntsville, Austin/San Antonio, we’ve seen double-digit percentage population growth in the last couple of years. The thing that cities across the southeast and Texas have in common for historical reasons: a lot of growth and perhaps infrastructure that doesn’t match that growth. Significant, in some cases, wealth inequality. Almost all these cities have a very significant lack of affordable, attainable housing stock to match up to that growth. Growth tailwinds. Historic disparities. There’s a lot of opportunity.

ImpactAlpha: Filling the early stage real estate development in those ‘Zoom towns’ does seem like a big opportunity. Can your strategy help mitigate the affordability challenge in these towns?

Baird: Absolutely. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development defines cost-burdened cities as cities where more than 30% of the population spends more than 30% income on housing. We made more investments in Austin than any other city – 48% of Austin is cost burdened. Other cities where we reinvested, like Charlotte and Greenville, are also cost burdened. With increasing workforce and affordable housing stock in cities that are growing in cost burden, it’s very necessary for cities to grow sustainably.