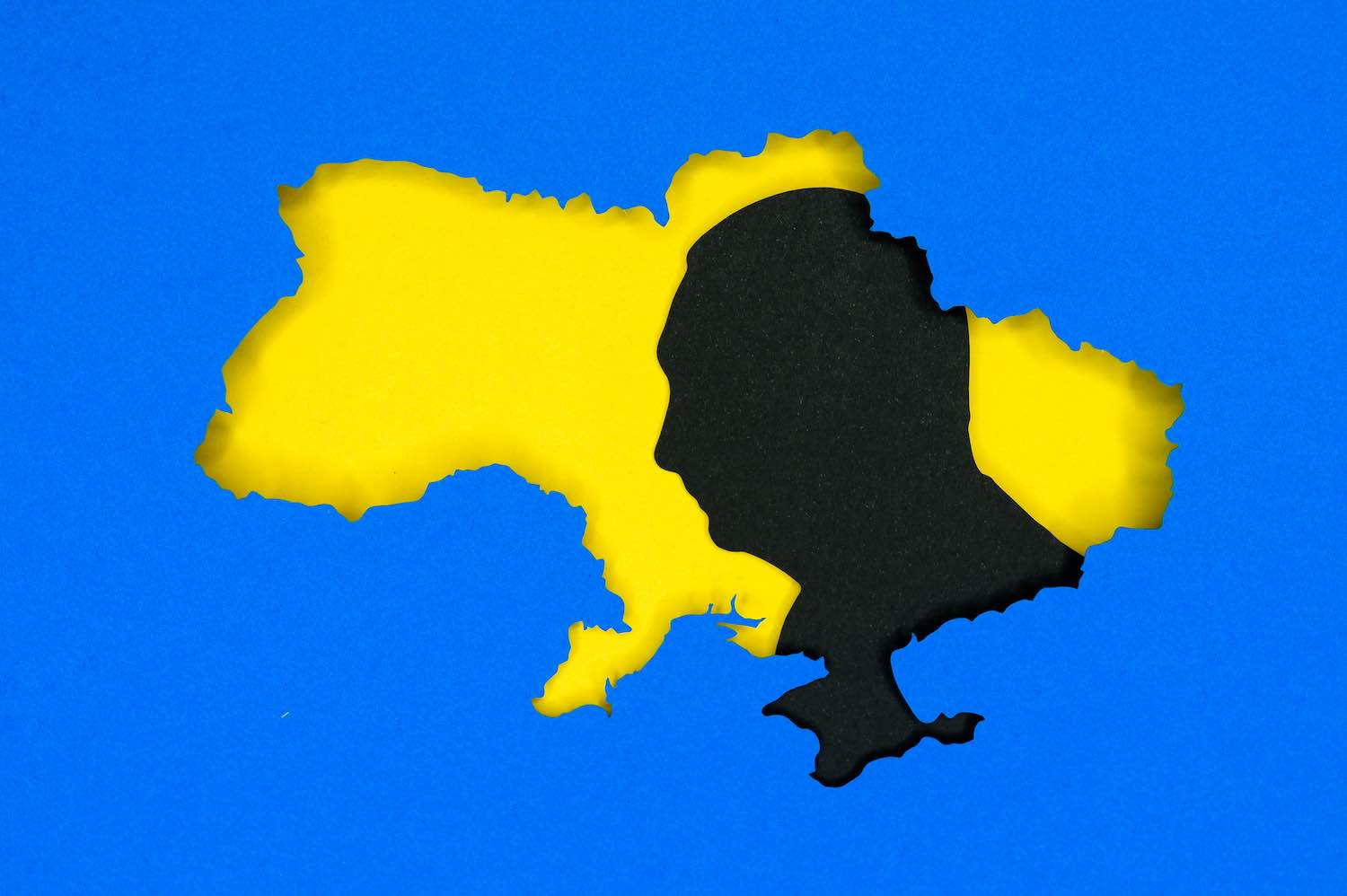

The scenes of brutal shelling and bombardment, along with heroic resistance and popular protests, have triggered a global response of solidarity and support.

It is hard to think about anything other than Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

As appalling as they have been, President Vladimir Putin’s actions are not exactly a surprise. In plain sight, Putin has been building Russia as an autocratic state that stank of corruption long before this current travesty of human rights and war. For too long, capital markets and modern business looked the other way as wealthy Russians poured money into art works, mega yachts, luxury housing, soccer teams, and election campaigns.

Along with global corporations, institutional investors are seeking to untangle their ties from Russia. Some are just managing their risks: with an increasingly high likelihood of default, rating agencies are downgrading Russian debt to junk. Others are responding to sanctions: Russia is being shut out of much of the global banking system. And some are complying with legislation or requests from elected officials. Those who do not divest are left watching the value of their Russian assets plummet.

The speed of the divestment from Russia dwarfs earlier divestment efforts, from South Africa to fossil fuels. And the coordinated effort has provided a demonstration of a different kind of divestment than we have seen before – quick, deep and coordinated, including with sanctions.

But if the war goes on, and Putin remains in power, how long will the resolve to stay out of a once-lucrative market last?

If it works, the divestment effort may rewrite the playbook. If it doesn’t, and investors and companies slink back, it may discredit divestment as a strategy for years.

History as prologue

Divestment has long been a contested topic in the world of asset management, both for its efficacy and its intentions.

Beneath the fierce debate over divesting from fossil fuel companies, it has been easy for actual institutional investors to effectively blow off divestment, by either doing as little as possible to comply, or refusing to divest entirely.

The carbon divestment movement took its inspiration from the campaign to prod institutional asset owners divest their money from companies doing business with apartheid South Africa, starting in the 1960s and peaking in the 1980s.

As with Putin today, the campaign sought to make the apartheid regime in South Africa a pariah on the world stage (and in the capital markets). Margaret Thatcher in the U.K. and Ronald Reagan in the U.S. were not willing to impose sanctions on South Africa. The U.S. did impose sanctions on South Africa in 1986 (Reagan’s veto was overruled by Congress).

The sanctions are credited as a contributing factor in ending state-sanctioned and enforced segregation. Apartheid ended in 1994.

Much of the socially responsible, now ESG, investing infrastructure, particularly in the U.S., was built out of the divestment movement. Organizations like the Interfaith Center for Corporate Responsibility and the Council of Institutional Investors came of age in that era. Corporations, most notably, General Motors, did pull out of South Africa (only to return in 2004 and then again end manufacturing there in 2017).

For institutional investors, the South Africa divestment campaigns were largely symbolic. And post-apartheid, activism driven divestment movements have tended to view divestment as a proxy for broader, and higher causes, which fiduciaries then argued was outside their purview.

In the case of Russia, they appear to have decided that the risks are material.

Kabuki theater

A large reason a lot of investment officers hate divestment is because it has often been little more than theater.

During my time as an investment fellow at the investment office of the University of California, an activism campaign targeted the U.C. to divest from Turkish bonds, as a protest against the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire, which took place during World War I, which resulted in the murder of more than one million Armenians.

It so happened that an important member of the California state legislature, with influence over the education committee, which oversees the budget for the UC Regents, had a significant Armenian constituency calling for divestment. So, Jagdeep Singh Bachher, the university regents’ chief investment officer, was summoned before a legislative subcommittee to testify (not under oath) about the university’s investment in Turkish bonds.

As Bachher explained to the subcommittee, the U.C.’s $160-ish billion investment office did have a small exposure to Turkish bonds, as part of a BlackRock emerging markets fixed-income fund. And, because the fund was a commingled account, it was impossible to divest from those assets. Bachher added that, in its endowment, rather than its pension plan, the U.C. did manage money for the American University of Armenia, based not far from the University of California offices in Oakland.

In the committee’s Q&A, a state legislator asked the obvious question: Does that mean that assets for the American University of Armenia are invested in Turkish bonds? No, Bachher said, because the far smaller endowment was invested differently from the pension plan. There was no exposure, he said.

That was not true.

As a look at the publicly available investment reports shows, the U.C.’s endowment is invested in the same BlackRock emerging market bond fund, just like the pension plan. Having worked on the prepared remarks, I was appalled by this glaring error. Almost no one else seemed to care.

The activists had gotten the spectacle they came for. The policy makers had achieved their goal of raising the issue and making an important constituent group happy. And the investment office could return to the important business of making money. That was what mattered.

With divestment, institutional investors are being used to score political points. They don’t like being made to look bad, and they don’t like politicians or other stakeholders interfering with how they do their job. (Deep irony: almost all leading investment officer roles are, in their own way, deeply political.) That’s why we go around and round on the never-ending Ferris wheel of fossil fuel divestment.

Russia, of course, is different.

Exit stage left, chased by a bear

From Alaska to Wisconsin, and from Australia to Canada to Norway, governments and lawmakers are asking pension plans, sovereign wealth funds, and public universities to divest. Asset managers are frantically figuring out how to unwind portfolios.

The rush to the exits has caught up even companies that might have preferred to stay, including Deutsche Bank.

General Motors (again) has said that it will suspend car exports to the country for the foreseeable future. McKinsey & Co. is among the firms that have said they will stop operating in Russia. Under pressure, retailers including McDonalds, Starbucks, and Pepsi have halted sales in the country.

The oil majors are seeing the economic cost of getting into bed with Putin’s Russia. BP is expected to take a $25 billion write down, after being pressured by the U.K, government to end its joint venture with Russian oil giant Rosneft. Weeks earlier, BP had staunchly defended its presence in Russia. Bloomberg called the “surprise move” a sign of how far Western powers were willing to go to punish Putin. Days later, both ExxonMobil and Shell announced they too would be cutting ties with Russia. Exxon’s Russia assets were estimated to be valued at around $4 billion, prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

These swift, costly, exits are the real life consequences of being willing to do business in parts of the world like Moscow that lack good governance or strong rule of law. The Wall Street Journal March 7 headline: “How Oil Giants’ Bets on Russia, Years in the Making, Crumbled in Days.”

“The pullout by the oil companies—which have cultivated relationships with despots for decades to extract fossil fuels in the Middle East, Africa and other dangerous corners of the world—demonstrates how quickly legal, political and moral concerns have combined to make doing business with Russia a perilous prospect,” the Journal wrote.

Which calls the question of how well the risks were appreciated earlier. We all knew what was going on in Russia, and with Putin. We knew that money and business empires of questionable origin were making their way into the banking and investment system. All the while Putin ruled Russia with a velvet glove and an iron fist, strangling civil liabilities and quashing any questions of his own wealth. We chose to look the other way.

Until Thursday, Feb. 24, 2022 when looking the other way became impossible.

On notice

If you want to understand how important access to the West’s economy, and its banking system, is to Russia and how very differently, and ruthlessly, business operates in the country I highly recommend Bill Browder’s book Red Notice.

A former hedge fund manager who made his money investing in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union, Browder is a controversial and, even in his own account, not a particularly likable figure. But the story of what happened to him, and more specifically his former advisor Sergei Magnitsky, in Russia and what Browder did afterwards ,is important to our understanding of the last decade of U.S., Russian relations as well as what is happening now.

Browder operated as an activist investor in post-Soviet Russia. Taking stakes in Russian companies and using the classic tools of shareholder activism to improve their corporate governance and make money. Initially his efforts were wildly successful. And, indeed, Browder welcomed Putin’s asset to power as a further liberating force in the country.

Then things turned dark. Putin’s government raided the offices of Browder’s hedge fund, accusing him of tax fraud. In 2009, the Ukrainian-born Magnitsky, who had been working in Russia for Browder was arrested, detained and appears to have been beaten to death by eight prison officers.

In the aftermath, Browder waged a campaign to prevent Russians accused of human rights violations from operating in the West, by using sanctions and freezing their assets. The so-called Magnitsky Act was signed by President Barack Obama in December 2012. Prosecutors were making progress when President Donald Trump took office in January 2016.

Browder equates Magnitsky’s death to that of Steve Biko, the South African anti-apartheid leader who was killed in police custody in the city of Port Elisabeth in 1977. A Ukrainian tax lawyer and a black civil rights leader who both paid with their lives in the fight against government sponsored corruption and oppression.

These were no proxy wars.

Divestment against a corrupt state is not a symbolic act of protest. It is an act of standing up to bad governments and bad governance. Had capital markets and governments acted strongly against the apartided South African government, or Putin’s Russian government, they would not have been able to pursue the policies that they did. If Thatcher and Reagan had stood up to the apartheid government, Biko and other activists may not have died.

Had we listened more clearly to the alarm bells that Browder has been ringing for over a decade, investors likely would not all now be running for the Russian investment exit doors. (I find Browder to be a less reliable critic of Putin generally or the current situation. Like all good campaigners, he tends to be myopically focused on his own issue.) Then again, Browder himself had to learn the lesson of not engaging with Putin the hard way.

To be clear, It is not the Russian people that are at fault. They are already suffering the bad outcomes that come from Putin’s toxic brand of klepto capitalism. But the institutions of the West, including capital from institutional investors, have allowed Putin and his allies to thrive with little regard for laws or civil liberties.

We can no longer afford the naivete of thinking that doing business with autocrats and oligarchs will somehow make them better actors. Rather it normalizes, and implicitly condones, the dangerous state-backed profit-laundering behavior that has taken place for the last decade.

Institutional investors – like all of us – are still on the hook.