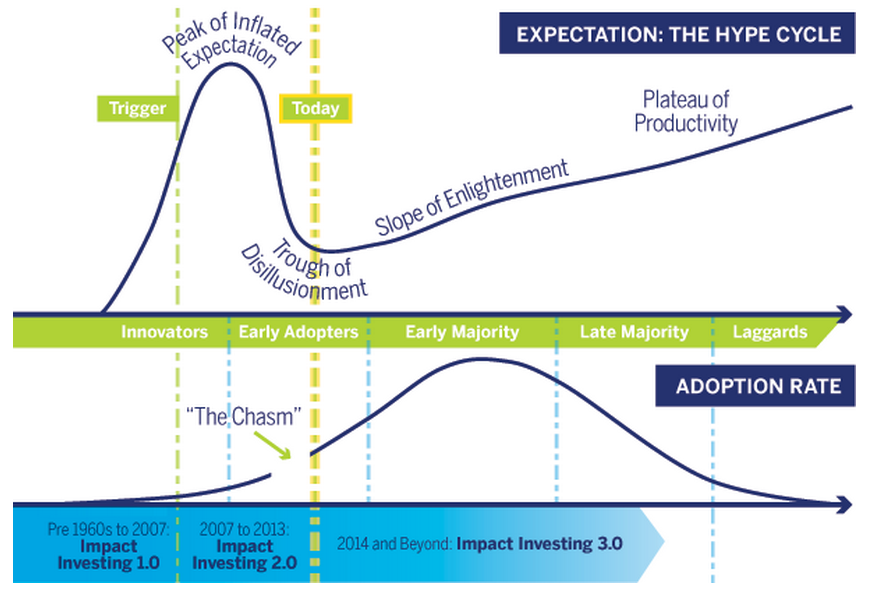

Emerging technologies follow a path to market adoption so well worn that it is known simply as “the hype cycle.” A hot new product category reaches the “peak of inflated expectations” only to inevitably crash in the “trough of disillusionment.” After a reset, the survivors climb the “slope of enlightenment” to the “plateau of productivity.”

“Impact investing” is an emerging set of financial practices more than a new technology, but it has also suffered a backlash of disillusionment after exciting sky-high expectations. Where are the deals? There’s no track record of results. Social impact is too tough to measure. Impact investing is just dressed-up philanthropy. And so on.

But just as some early champions of impact investing have begun to feel fatigued by the challenge of adequately explaining its potential, new institutions and individual investors are stepping forward to adopt a range of impactful approaches.

At the risk of again inflating expectations, impact investing’s climb up the slope of enlightenment stands to catalyze hundreds of billions of dollars over the next decade for investments in smallholder agriculture and food security; access to basic services such as water, electricity and sanitation; small business and economic development in both developing countries and U.S. inner cities; businesses led by and serving women and girls; sustainable real assets such as timber, energy efficiency and wastewater treatment; and many other sectors.

“We have a saying around here that sustainability is about four billion more people wanting to eat chicken and drive a car,” says David Chen, co-founder of Equilibrium Capital. As global population approaches nine billion, the emerging global middle class is creating unstoppable demand for food, water, energy, education, healthcare, financial services, housing and sanitation. Resource constraints and climate change demand disruptive innovation and radical efficiency. That makes impact a signal for long-term outperformance, he says.

“Investors now see sustainability not in terms of ‘values’ and ‘responsibility’ and ‘obligation’,” Chen says. “They now see this in broad economic terms. They’re seeing a shift in economics. They’re seeing value that’s being created.”

IMPACT 3.0

Call it impact investing 3.0. The first stage of impact investing, by a variety of other names, dates to the 1970s, when community development finance institutions and other financial institutions tapped private capital and government subsidies to invest in housing and inner-city businesses. “Socially responsible investors” screened out of their portfolios holdings with negative impacts, such as tobacco companies.

Ushering in the second stage, the term “impact investing” itself was adopted in 2007, by a gathering of leaders brought together by the Rockefeller Foundation at Bellagio, the philanthropy’s retreat center on Lake Como in the Italian Alps. The next year, Rockefeller’s board approved a $38 million initiative to build marketplace infrastructure around impact investing. Rockefeller’s initiative helped launch institutions such as the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), a kind of trade association for foundations, investment funds, banks and service providers; the Impact Reporting and Investment Standards (IRIS), a uniform set of definitions and metrics for social, environmental and financial performance; and the Global Impact Investing Rating System (GIIRS), an effort to assess and benchmark impact companies and funds much like Morningstar rates mutual funds and other investments.

Underlying the whole effort was a desire to catalyze private capital as a supplement to limited philanthropic funding and shrinking public-sector dollars for the social services safety net at home and development assistance abroad.

This network of organizations adopted a working definition of impact investments as investments made into companies, organizations and funds with the intention to generate measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return. The network took a broad view of impact investments, encompassing both emerging and developed markets and financial returns that ranged from below-market to market-rate.

In the years since 2007, an endless flow of white papers and panel discussions have explored every nuance of impact investing definition and practice, alternately inflating the bubble and popping it. A recent review of those discussions in the Stanford Social Innovation Review by Paul Brest, the former president of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and his colleague Kelly Born, was in the bubble-popping mode, narrowly defining what could be considered genuine impact and expressing “concerns about potentially unrealistic expectations of simultaneously achieving social impact and market-rate returns.”

Indeed, some early impact funds, such as Acumen, which is primarily backed by philanthropic capital, expect little more than the return of their capital. Acumen’s focus on innovative ways to serve the poor in south Asia, Africa and Latin America means it’s willing to accept higher risks, in terms of new technology, business models and target markets. Tucked into a report Acumen issued last year were details that showed Acumen’s portfolio companies have an average after-tax loss of 20 percent. Its eight most profitable investments returned profits of just 6 percent. The report noted that such returns are “far off the expectations of mainstream financial-first investors.” Of course, a full return of capital, even without a premium, is far better financially than a philanthropic grant that represents a guaranteed 100 percent loss.

But a funny thing happened as the action has moved away from philanthropic circles and academic journals. Actual investors began finding their own way to create impacts. The third stage of impact investing, now underway, is driven by growing demand from purpose-driven investors, both large and small, for access to opportunities and investment vehicles that increasingly make economic sense.

A younger generation, in particular, began to question the old division between financially driven investment, on one side, and philanthropy on the other. With the “generational transfer of wealth” well underway — the oft-cited inheritance of an estimated $41 trillion that Millennials and Gen-Xers will get from their Baby Boomer and Greatest Generation relatives — wealth managers and financial advisors are keen to respond to the concerns of younger investors. A recent Deloitte survey of Millennials about “the primary purpose of business” found the highest number (36 percent) stating “improve society,” even more than “generate profit” (35 percent).

RISKS AND RETURNS

At the same time, a reassessment of global risks and returns led many investors and fund managers to look harder for opportunities that fit in their portfolios and met their expectations of returns, both financial and social. The financial meltdown put the very notion of risk-adjusted market-rate returns up for grabs. The global economic slowdown had the silver lining of making benchmark comparisons much easier for alternative investments. Mainstream venture capital returns, for example, haven’t significantly outperformed the public market since the late 1990s, and, since 1997, less cash has been returned to investors than has been invested in venture capital funds, according to a report from the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. Turmoil in Europe and elsewhere cast a new light on risks, while fast growth in emerging and frontier markets opened eyes to new growth opportunities.

The volatility of public markets caused many investors to rebel against “short-termism” and look for sources of long-term growth, and especially assets uncorrelated with swings in the public markets. Steady returns of five to six percent over 15 or 20 years can trump volatile results, even if they may be higher in the short-term. The inescapable implications of climate change, for example, opened eyes to a whole array of global issues, from food and water shortages to still-widespread energy poverty. A new group of asset managers began to present impact not as a new form of noblesse oblige but as an attractive investment strategy in a risky world.

“The customers of the portfolio companies that we invest in are asking for better access and better value. They want financial services. They want housing. They want health care,” says Maya Chorengel, managing director ofElevar Equity, which invests in such services in Asia, Africa and Latin America. “They already spend a lot of their hard-earned, hard-fought money on very, very insufficient, inconvenient services and products in these spheres, or they’re not served at all. If they are given these services, if they are given access, they have the opportunity to unleash their economic potential and great social impact ensues.”

Elevar, which is raising $70 million for its third fund, is one of more than 200 identified impact private equity and venture capital firms, many of whom are raising new funds on the basis of actual performance. LeapFrog Investments, which provides insurance and other financial services for “the next billion” in developing countries, recently announced it closed on $204 million of a planned $400 million second fund, triple the size of its first fund of $135 million. Investors include insurance companies like MetLife, Prudential and Swiss Re and banks and asset managers including JPMorgan Chase and TIAA-CREF. Leapfrog has pioneered micro-insurance products, such as life insurance for people with AIDS in South Africa. “You can have businesses that are purpose-driven and outperform their conventional peers,” says Andrew Kuper, LeapFrog’s president.

SJF Ventures, for example, was oversubscribed for its third fund, which closed earlier this year at $90 million, with participation from Citi, Deutsche Bank and State Street Bank, as well as from several foundation endowments attracted to its focus on recycling, health and education technology and sustainable agriculture. City Light Capital, which invests in ventures tackling challenges in education, energy and safety and security, has co-invested with 45 venture capital firms, none of which are identified as impact investors, says founder Josh Cohen, an indicator of its mainstream appeal. At the same time, he says, City Light’s impact intent gives it an edge among mission-driven entrepreneurs looking for aligned investors. Unitus Seed Fund raised $8 million to make investments in “base of the pyramid” startups in India, including from legendary venture capitalist Vinod Khosla. “Investors, entrepreneurs and businesses can create wealth for themselves by providing value to the masses,” Khosla said at the time.

This more profit-friendly approach has made it easier for major financial service providers to enter the market, and most big banks and wealth managers are scrambling to retain the loyalty of high- and ultra-high-net-worth clients with impact investing products and services. Morgan Stanley last year rolled some existing and new services into its Investing with Impact Platform. UBS has just raised a $55 million Small and Medium Enterprise Focus Fund to invest in small businesses in developing countries. Credit Suisse is raising a $500 million fund targeting agriculture in Africa. Deutsche Bank has been raising a $50 millionEssential Capital Fund with an innovative approach to providing higher risk “first loss” capital for impact ventures that can then attract additional capital from more risk-averse social investors.

It is too early to fully assess the returns of many impact investments. But a survey of impact funds by the World Economic Forum (WEF) — the sponsors of the annual gathering of movers and shakers in Davos, Switzerland — found that 70 percent targeted internal rates of returns of more than 11 percent, with half of those targeting 20 percent or more. “Impact investing is unique in that the investor may be willing to accept a lower financial return in exchange for achievement of a social outcome; mainstream investors have thus often assumed that impact investments always generate below-market returns,” the WEF’s report said. “This is not true.”

Impact initiatives deliver ancillary benefits as well. Executives of major banks and financial service providers told the WEF that their active participation in impact investing boosts engagement and motivation of their investment teams, signals an emphasis on long-term value creation and, most importantly, drives higher investor commitments. “Mainstream investors agree that impact investing has the potential to drive a distinct competitive advantage,” the WEF concluded.

CLIMBING THE SLOPE

To be sure, impact investing still has a long climb to fulfill projections of an impact investing marketplace of $500 billion to $1 trillion by 2020. The consensus of various estimates is that the impact investing market currently stands at about $25 billion. The GIIN’s ImpactBase, a database of impact funds and investment products, includes 262 funds with $23 billion under management (and $15 billion in committed capital). That’s a large-sounding number, but a tiny fraction of the estimated $70 trillion in global assets under management.

The growth of dedicated impact venture-capital or private equity funds won’t be enough. To really climb that slope of enlightenment, impact investing will have to attract the mass market of smaller “retail” investors and the “real money” of major pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds. That shift has barely begun — but it has begun.

The advent of crowdfunding options for investors has created a rush to offer retail investors impact investments through new platforms such as the UK’s new Social Stock Exchange, the Toronto stock market’s Social Venture Exchange and the Impact Investment Exchange, based in Mauritius, to support listing, trading, clearing and settlement of securities issued by social enterprises in Africa and Asia.

That’s small potatoes to Gloria Nelund, CEO of the TriLinc Global Impact Fund, which has registered to raise as much as $1.5 billion (through individual investments as low as $2,000), to provide loans and trade finance for small- and medium-sized businesses in developing countries. As of July, the fund had invested $3.5 million in seafood businesses in Ecuador and a sustainable timber exporter in Chile. The fund will track and report to investors impacts such as job creation, wage increases and employee ownership, as well as specific criteria selected by portfolio companies, such as access to clean water.

“How do you create an impact financial product that solves a real problem you can track and measure and report back, and also generates a competitive financial return?” asks Nelund, who headed wealth management units at Deutsche Bank and Bank of America. In-country, TriLinc relies on local sub-managers with knowledge of customers who agree to abide by TriLinc’s impact-tracking methods. For investors, she works through a distribution network of financial advisors looking for new products to offer socially minded investors. “I’m going to prove you can generate a competitive financial return and generate impact, but you have to change how things are done,” she says.

The impact marketplace is changing in other ways as well. Mostly gone is the brief infatuation that impact represented its own “asset class,” alongside public securities, private equity, fixed income and the like. Rather, impact is now seen as a factor across all asset classes. The W.K. Kellogg Foundation, for example, which earmarked $75 million from its endowment for mission-driven investing, tries to drive impact in all its holdings, not only private equity, but also fixed income, mezzanine debt and even cash.

HIP Investor, an advisory firm in San Francisco, provides impact ratings for municipal bonds. The firm’s CEO, Paul Herman, says the ratings can uncover hidden risks. “Let’s say there’s an electricity-generating entity in Utah that’s associated with coal,” he says. “They ship to Los Angeles and issue municipal bonds. To date they’ve been considered attractive. But now there are big wind farms in southeast California. That’s cleaner power, closer to LA. So on one side there’s a risk, coal, and on the other side, an untapped opportunity, a wind farm. We ask: Is the carbon risk priced in?”

LONG-TERMISM

Risk mitigation, even more so than upside potential, may turn out to be impact investing’s major appeal. Climate change presents the most obvious risks, including not only extreme weather, but, for example, political risk from popular uprisings caused by food or water shortages. Other impact investors are starting to ask about the business risks of under-representation of women in key roles when women globally are increasingly in charge of households, and even corporate buying decisions.

The $258 billion public-employees pension fund, California Public Employees Retirement System, or CalPERS recently adopted a set of ten new investment principles to nudge portfolio managers toward a new approach. Fund managers should account not only for technical market factors, but broad societal risks such as resource-availability, the principles state, making clear that “A long-time investment horizon is a responsibility and an advantage.”

“This is a major institutional investor stepping up and saying we want to see some change in the mainstream economy,” says Janine Guillot, who recently stepped down as CalPERS’ chief operating investment officer after helping spearhead the adoption of the new principles. “I think the idea of sustainability is a mainstream idea. We shouldn’t create some parallel economy, we should have a mainstream economy that’s focused on sustainability.”

Pension funds are already investing in clean tech, low-income housing, energy retrofits and such assets as water districts, sewage treatment and air scrubbers, based on their financial benefits. Allen Emkin, managing director of Pension Consulting Alliance, who advises many large pension plans, sees huge potential in water storage, food production and energy transmission. “There’s unlimited capital if it’s structured right,” he says.

As impact investing goes mainstream, the danger, of course, is that it loses its impact. “To me, the big risk is that we cherry-pick the slightly easier-to-serve populations and ten or 15 years from now, for the toughest-to-reach, largest segment of the population, we actually haven’t made a whole lot of progress because we skipped a step,” says Sasha Dichter, Acumen’s chief innovation officer.

And many hard-to-reach markets and innovative business approaches do indeed need below-market, concessionary capital for some period of time before they can deliver competitive returns. “We’ve gone from this world where everybody said, ‘Look, there has to be a discreet trade-off. In order to have more social impact, you’ve got to accept lower returns.’ We threw out that paradigm and we’ve said, ‘There’s not necessarily a trade-off between social impact and financial return,’” says Matt Bannick, managing director of Omidyar Network, the philanthropic investment fund of eBay founder Pierre Omidyar and his wife Pam, which makes both market-rate investments and more traditional grants in areas that need technical assistance, marketplace building or just simply subsidies to get started.

“The danger is that some people have gone all the way and said, ‘There is no trade-off between social impact and financial return.’ The reality is that frequently there is a very distinct trade-off.”

The frontier for impact investing, then, is to match different kinds of investors with the deals that give them the kind of returns they are looking for, in terms of upside opportunities, downside risks and social and environmental benefits. David Chen of Equilibrium Capital suggests that represents an opportunity for the financial industry to rebuild its reputation through financial innovation aligned with environmental sustainability and economic inclusion.

Just as financiers in recent decades have learned to dissect and repackage risky assets — say, turning subprime mortgages into investment-grade instruments — so too can they dissect and repackage benefits, so that positive social and environmental impacts can be valued and priced and sold to investors with those expectations for their portfolios.

“When the economics are aligned, when the incentives are aligned, when the language is aligned,” Chen says, “the capital markets can react at a blindingly fast speed.”