ImpactAlpha, May 2 – It’s one of the conundrums of the pandemic: commercial capital is pouring into off-grid electricity companies in Africa and elsewhere, but progress toward expanded access to energy has stalled.

Sun King, which makes and sells small solar lanterns and home units in 40 markets, last week raised $260 million in equity, led by BeyondNetZero, General Atlantic’s climate investing arm. The Series D financing for Chicago-based Sun King, formerly known as Greenlight Planet, was one the largest raises ever in off-grid solar.

In March, Nairobi-based M-KOPA raised $75 million, led by Generation Investment Management. Last September, San Francisco-based Zola Electric raised $45 million in equity and a similar amount in debt. Zola’s investment was led by TotalEnergies Ventures, the venture capital arm of the French oil giant TotalEnergies, along with DBL Partners, Helios Investment Partners, Vulcan Capital and Lyndon and Pete Rive, founders of SolarCity and cousins of Tesla’s Elon Musk.

BBOXX, which has raised close to $200 million in debt and equity and is in talks to acquire Ghana-based peer, PEG.

Investor confidence in makers of solar lanterns and small home systems reflects expectations that such systems will play a major role in providing energy access for the 770 million people around the world who still lack access to reliable electricity. The International Energy Agency’s scenario for full energy access forecasts that more than half of those energy-poor households will need decentralized solutions before 2030.

But last month’s same IEA report found that progress toward broader energy access stalled during the COVID-19 pandemic, after the number of people without electricity, fell an average of 9% per year from 2015 to 2019. In Africa in 2020, the number of people without access to energy actually went up for the first time since 2013.

Population growth and economic hardship caused by the pandemic are largely responsible for the contradiction. But it is also partly explained by the strategic pivots of early off-grid energy providers as the distribution solar industry has grown up. Off-grid energy providers such as M-KOPA and Zola, as well as BBOXX, d.light and Sun King, have stuck it out in a sector that now reaches hundreds of millions of customers. But nearly all have survived by shifting their business models.

“We’ve seen some companies move upmarket because there’s more pressure on margins, and profit ratios need to be bigger, as you go to more commercial funding,” says Kat Harrison of 60 Decibels, an impact management and research firm that has had a long-running focus on the social impact of off-grid solar products.

At the same time, the opportunity to provide new products and services to a broader base of customers has also grown, particularly with the acceleration of mobile phone and mobile money adoption.

In a roadmap released last year, U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres called for investments in universal energy access of $35 billion a year to reach another 500 million people with electricity by 2025.

That sets up off-grid solar as a test case for impact investors who helped build the sector: Can the early focus on the poor survive the transition to commercial capital?

Shifting strategies

For-profit social enterprises serving rural, low-income and other disenfranchised populations have a difficult needle to thread. They have to design and distribute products and services—often from scratch—with extreme affordability and access in mind. Then they have to prove that their models can scale sustainably and profitably. Charge too much or grow too quickly, and they’re accused of exploiting the poor for profit. Grow too slowly or rely too long on grant and concessional capital, and they’re accused of being unsustainable or uninvestable.

Dozens of companies are now providing low-cost solar products and services. Collectively, these companies have helped more than 300 million customers access reliable, clean energy for the first time and introduced many to credit and other forms of digital financial services.

“Commercial capital is needed when impact capital is not able to support companies anymore,” explains Christian Schattenmann, energy access lead for Geneva-based impact investor Bamboo Capital. “Without more mainstream-oriented capital they would run out of steam.”

Bamboo was an early backer of Sun King, investing in its $4 million Series A round a decade ago. It also invested early in BBOXX, which secured investments from Mitsubishi Corporation and South African financial services group Old Mutual after securing partnerships with the government of Togo, French utility EDF and solar manufacturer Victron Energy.

Acumen, Omidyar Network, Blue Haven Initiative and other impact investors have helped off-grid solar startups navigate early growing pains and missteps. Patient impact capital was crucial to helping companies test new products, services and distribution channels, and establishing sustainable business models that commercial capital could help grow.

“You need patient impact capital to build the business before commercial capital can take over for further scale,” says Schattenmann. “Some of our portfolio companies have reached that scale and are accessing commercial capital.”

But he warns, “Off-grid solar is a tough and complicated business where companies need to excel on multiple fronts: product design, last mile distribution, consumer financing. Only the most efficient companies are able to survive and become financially sustainable so that they can achieve social and environmental impact at scale.”

The issues are not new. Ceniarth’s Diane Isenberg and Greg Neichin called them out in a 2017 essay that said the then-nascent boom in commercial capital “may be too much, too fast for a sector that still has not fully solved core business model issues and may struggle under the high growth expectations and misaligned incentives of many venture capitalists.”

Sun King launched in 2007 as Greenlight Planet to sell solar lanterns and other small-scale solar lighting products. Its products now reach more than 80 million people, nearly half of whom live below the international poverty line. It still uses a direct-to-consumer sales model, distributing its products via a network of more than 15,000 agents, but it has expanded its range of products to include solar irrigation pumps and larger solar home systems.

BBOXX launched in 2009, manufacturing and selling its own small-scale home solar systems in rural Rwanda. It too has maintained its focus on low-income consumers, and recently launched a new product, Flexx, for “entry-level” rural customers. It now also partners with governments, solar manufacturers and utility operators to reach urban consumers, as in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and sells larger-scale systems for cities and small commercial businesses. It has also expanded into liquid petroleum gas to convert customers to cleaner cooking fuel. Customer data now plays a key role in the company’s growth plans, a spokeswoman explained.

If it acquires PEG, the deal will expand BBOXX’s presence in West Africa and solar provision to healthcare clinics and other community businesses.

Zola launched as Off-Grid Electric to sell solar lanterns and home solar systems in Tanzania. Much of its growth is now fuelled by larger-capacity systems that are designed to replace diesel generators for urban consumers and businesses connected to unreliable electricity grids. GE Ventures backed Zola shortly after it launched its Infinity back-up solar power system.

M-KOPA, like its peers, started in single-purpose solar products and home solar systems but is now focusing its growth in new markets around financial services.

“M-KOPA’s connected asset financing platform has since diversified to include, in addition to solar, a broad range of products and services such as smartphones, cash loans, health insurance and later this year e-mobility to increase its impact across the continent to drive digital and financial inclusion, as well as sustainability,” a spokeswoman for the company told ImpactAlpha.

Access to finance

Companies like Solar King, BBOXX, M-KOPA and Zola emerged roughly a decade ago to enable cash-poor customers to pay for costly products over time with so-called “pay-as-you-go,” or PAYG, distribution and sales models for solar energy.

Their thesis: that devices such as solar lanterns and clean cookstoves can pay for themselves over time in decreased fuel costs and other benefits. Also: that there needed to be a financing mechanism to help the rural poor cover the upfront cost of a basic $10 lantern or $200 home solar system.

The PAYG lending model is credited with helping 25 to 30 million poor, mostly-rural consumers switch from using dirty and unhealthy kerosene lamps, candles and charcoal. It continues to evolve and expand, with a raft of next-generation startups broadening the base of rural, off-grid consumers that have gained access to solar energy for the first time.

Those that continue to focus on the most basic products and financial services remain the domain of philanthropic and concessional capital. Bamboo Capital, for example, offers results-based and catalytic grants to spur solar access in Haiti and Madagascar. Such types of financing are required “when you want to support the development of a nascent sector, particularly when companies are operating in a challenging environment,” says Schattenmann.

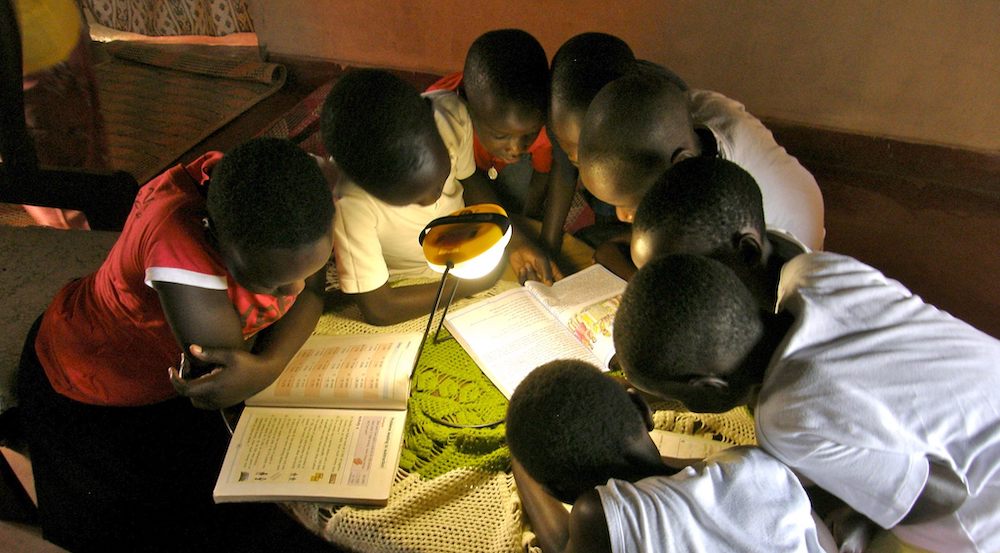

Field research from 60 Decibels with more than 21,000 solar home-system users in 22 countries found that pay-as-you-go, or PAYG, products and services have an overwhelmingly positive impact on lives and livelihoods. More than 60% of customers’ lives had “significantly improved” as a result of the solar systems because they have access to brighter, safer lighting; can save money relative to alternative energy options; enjoy the convenience of charging their phones and other devices; feel safer; and can enable their children to study after dark.

The majority of the respondents (59%) live below the international poverty line of about $3 per day; 71% said the systems were good value for money and 87% felt they were adequately informed of their contract terms and repayment expectations.

Furthermore, PAYG solar is often the first step on the formal financial services ladder for many rural consumers. 60 Decibels found that 63% of solar home-system users accessed their first line of credit when buying their systems.

A quarter of the solar home-system users in 60 Decibels’ research said the systems were a financial burden. 60 Decibels found that about 36% of solar-home customers elected to cut back on other household expenses during COVID, including food, to avoid losing energy access or reverting to kerosene or candles.

“The numbers show prioritization and choice – the value that customers place on having energy in their homes,” says Harrison.

Consumer protection

As the spectrum of players in off-grid solar shifts and expands, there’s recognition that in order to continue to serve low-income consumers, the key is enabling access to finance – that means new financial services and products, and consumer protections.

60 Decibels and the Global Off-Grid Lighting Organization, or GOGLA, have partnered on a pilot on consumer understanding of solar financing contracts and payment terms, the results of which are forthcoming. GOGLA, the main industry body for the off-grid solar sector, launched in 2019 the Gogla Consumer Protection Code as a “de facto industry standard” and framework for off-grid solar companies to measure their performance. More than 40 companies have signed on, including Sun King, BBOXX and M-KOPA (Zola is not a listed signatory).

“BBOXX recognises that consumer protection in the off-grid solar sector is important to safeguard positive impact for customers, accelerate further sustainable growth in the sector and build strong customer brands,” a spokeswoman for the company said. It provides contract terms and conditions in local languages, provides customers with regular payment receipts and outstanding balance updates, and uses incentives, monitoring and sanctions with its sales staff “to deter mis-selling or over-selling to consumers.”

Many companies also have practices in place to help customers through periods of financial hardship. M-KOPA customers that are “struggling with payments, suddenly hit with financial difficulty or are simply not satisfied with the product experience,” can return their product for a full or partial refund of their deposit and cancel their loan obligation risk-free, said M-KOPA’s spokeswoman.

The long-term success of off-grid solar depends on quality products and consumer protection, says Schattenmann. “This is a large industry now and – as in any industry – there are people who don’t behave responsibly or seek short-term gain. But unethical behavior is clearly an exception and not systematically happening in the industry.” “Unlike in the microfinance industry, there is actually no risk of over-indebtedness or ‘debt traps’,” Schattenmann adds. “The essence of PAYG is that people only pay as they go. If they don’t want the product anymore, they just stop paying.”