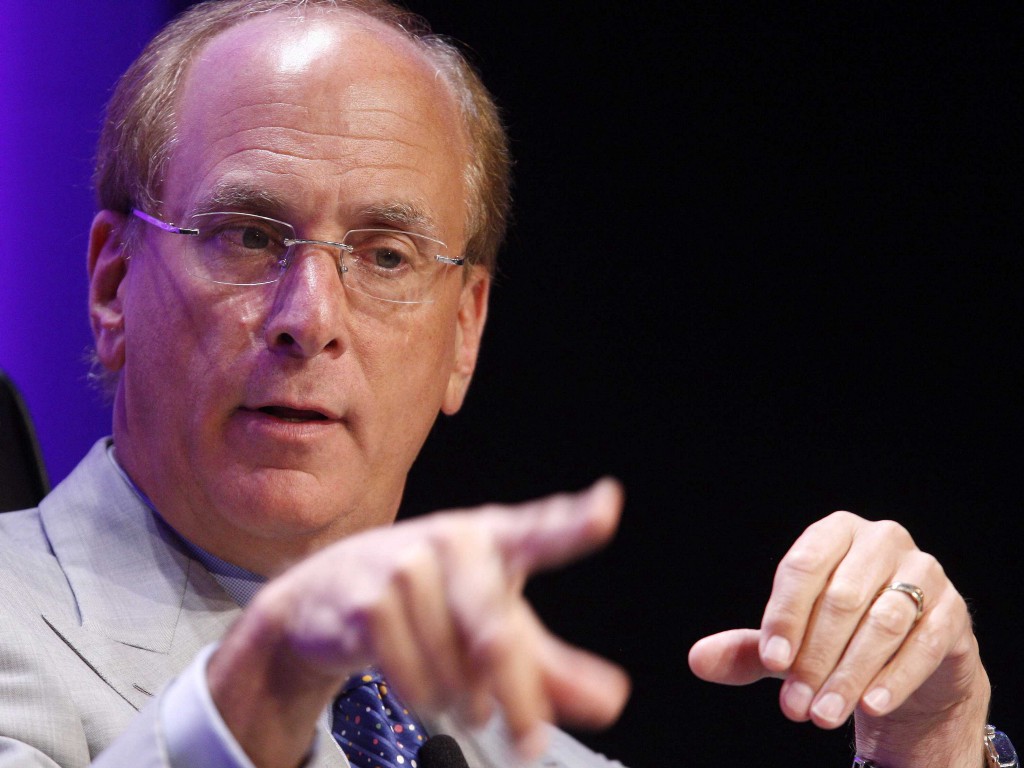

It was the letter read ‘round the world. The annual letter from BlackRock CEO Larry Fink sent corporate chieftains scurrying to their investor and public relations managers to find a purpose, and fast.

The latest episode of the Returns on Investment podcast pulls apart not only Fink’s letter, but the strong reactions to it. Corporate raider Sam Zell commented, “I didn’t know Larry Fink had been made God” (to which our podcast regular, Imogen Rose-Smith, replied, “I think BlackRock’s $6.3 trillion in assets made Larry Fink God.”)

Cash hoards

Overlooked in much of the commentary over Fink’s letter was his preoccupation with a growing concern: the demand from short-term “activist” shareholders for the return of ever-greater amounts of corporate cash to shareholders in the form of buybacks and dividends. Fink wrote:

Without a sense of purpose, no company, either public or private, can achieve its full potential. It will ultimately lose the license to operate from key stakeholders. It will succumb to short-term pressures to distribute earnings, and, in the process, sacrifice investments in employee development, innovation, and capital expenditures that are necessary for long-term growth.

As Returns on Investment host Brian Walsh put it, “He’s saying, ‘I’m looking out for you. I’m trying to help. I’m trying to protect you from these corporate raiders and activists, from the pressures you may face.” The assumption that companies will buy back shares, especially after the U.S. tax bill cut corporate taxes, is baked into their share prices.

According to numbers compiled by Bill Lazonick, an economics professor at the University of Massachusetts in Lowell, companies that have been in the S&P 500 for the last decade have used 93% of their total net income in that period on buybacks and dividends, or a total of about $4 trillion on buybacks and another $2.9 trillion on dividends.

“It’s the main driver of extreme concentration at the very top, of the disappearance of the middle class,” Lazonick told ImpactAlpha. “It’s becoming serious enough that people are saying, let’s do something about it.” Because such buybacks starve companies of capital that could be invested in worker productivity or growth, Lazonick has a simple proposal: ban buybacks.

Fink doesn’t go that far, but warned, “Tax changes will embolden those activists with a short-term focus to demand answers on the use of increased cash flows, and companies who have not already developed and explained their plans will find it difficult to defend against these campaigns.”

Erika Karp, CEO of Cornerstone Capital Group, agreed investors should look at how companies use their cash as an indicator for future growth. As companies automate operations, she said, “One company takes those gains, and uses profit improvements to pay back to shareholders. Another company is taking those gains, investing [them] back, looking for growth opportunities and hiring more people at higher wages.” She asks: “Are you spending the money to return to shareholders, or to grow the company?”

Reader response

Last Friday, we asked ImpactAlpha’s readers for their reactions to Fink’s letter. Perhaps not surprisingly, the comments were overwhelmingly positive.

“If BlackRock can influence its investment portfolio and provide financial benchmarks for their investments that matter to the socially conscious generations that are coming up, then we can begin to include these things as ‘real’ criteria and not just ‘must do for the optics,’ and drive real institutional change,” wrote Jory Tremblay of Fig Solutions. “I applaud him for standing up and raising the issue and broadening the dialogue.”

“My best investments from a returns perspective have ALL been those with impact,” wrote Margit Pearson. “You just have to have a lens longer than two quarters.”

“A sea change! Cannot be underestimated,” said Lawrence Bloom of the Be Earth Foundation. “He now needs to show how they monitor and impact!”

Carolin Schellhorn had a very simple definition of “purpose” for companies: “Address at the very least one of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals.”

“It is a big deal,” wrote Joe Milam.

https://medium.com/media/f35755ed98c3fbc25b5c6cef79a4b56c/href

Passive investing

The most salient critique of Fink’s letter is that he lacks the tools to enforce it. Because BlackRock is largely an index investor, it will rarely, if ever, divest from a company’s stock over questions of social responsibility. It has stepped up its corporate engagement activities, however, and last year took the dramatic step of opposing management at both ExxonMobil and Occidental Petroleum in supporting shareholder resolutions demanding comprehensive reporting on the oil companies’ exposures to climate-related risks.

BlackRock tips shareholder vote to press oil giant on climate risk

That brings up the question of which companies get included in the indices. Companies do fall out of the S&P 500 and other indices because of share performance or other reasons. Andrea Armeni of Transform Finance notes that the Council of Institutional Investors has applauded both the FTSE Russell and S&P Dow Jones moves to ban companies with voting-rights structures that foreclose meaningful shareholder engagement. “This is something to pay close attention to,” Armeni says.

Milton Friedman

Inevitably, any discussion of corporate social responsibility must return to the original text, the 1970 New York Times Magazine article by economist Milton Friedman that declared “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profit.”

The businessmen who believe that they are defending free enterprise when they declaim that business is not concerned “merely” with profit but also with promoting desirable “social” ends; that business has a “social conscience” and takes seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers. In fact they are–or would be if they or anyone else took them seriously–preaching pure and unadulterated socialism. Businessmen who talk this way are unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades.

In an interview with CNBC, Fink took a revisionist stance on Friedman’s doctrine, pointing to a few of the caveats the economist allowed might justify corporate social activity. For example, Friedman wrote, “It may well be in the long run interest of a corporation that is a major employer in a small community to devote resources to providing amenities to that community or to improving its government. That may make it easier to attract desirable employees, it may reduce the wage bill or lessen losses from pilferage and sabotage or have other worthwhile effects.”

Likewise, Fink wrote, “Companies must ask themselves: What role do we play in the community? How are we managing our impact on the environment? Are we working to create a diverse workforce? Are we adapting to technological change? Are we providing the retraining and opportunities that our employees and our business will need to adjust to an increasingly automated world?”

“Without a sense of purpose, no company, either public or private, can achieve its full potential. It will ultimately lose the license to operate from key stakeholders,” Fink wrote. “And ultimately, that company will provide subpar returns to the investors who depend on it to finance their retirement, home purchases, or higher education.”

Yes to social purpose, Fink is saying, and yes to corporate profits. Let the debates roll!