As our children head back to school this Fall, there are still hundreds of millions of students in low- and middle-income countries suffering the consequences from the Covid-19 pandemic, and its subsequent lockdowns. The setbacks have affected both state and non-state education providers.

A central piece in the recovery puzzle will be the ability to draw in more private capital from investors, equipped with innovative financing instruments to back solutions with high impact potential for enhancing equitable outcomes.

The Education Finance Network, developed by USAID, is convening diverse education stakeholders with a focus on leveraging non-state resources to create inclusive, high-quality education systems in low- and lower-middle income countries. Members include donors and investors, as well as education practitioners.

Education finance

Even before the pandemic, the IFC estimated that the investment required to achieve the targets set out in Sustainable Development Goal 4: Quality Education for All, was a sizable $250 billion annually. When accounting for the learning losses experienced since then, that number will have increased.

Of the estimated $715 billion assets under management in the impact investment market in 2020, the Global Impact Investing Network estimates that only 3% are currently being allocated to education. The sector has been experiencing a decrease in investment with a 7% shrinkage year on year, since GIIN’s last survey, back in 2015.

Still, evidence shows both the impact and the financial promise surrounding educational investments:

- Inclusive growth. There is a wealth of academic literature illustrating that for every $1 spent on education, as much as $10 to $15 can be generated in economic growth. If 75% more 15-year-olds in the world’s poorest countries were to reach the lowest OECD benchmark for mathematics, 104 million people could be lifted out of extreme poverty, according to UNESCO.

- Investment opportunities. There are a number of opportunities for investors to leverage innovative financing instruments, such as impact bonds, income share agreements, and blended finance to help improve quality in existing education systems by designing services that specifically target the most underserved groups, both by supporting core service delivery of basic education and investing in ancillary services that can strengthen education systems as a whole.

Pandemic-era setbacks

Between February 2020 and February 2022, schools globally were closed on average for about 141 days, with children in South Asia and Latin America losing on average 273 and 225 days of school respectively, according to a recent UNICEF report.

The effectiveness of distance learning efforts has varied tremendously across the world. The lack of connectivity and digital skills among teachers made it impossible for many students in low- and middle-income countries to rely on the internet and e-learning platforms as a replacement for in-person classes.

In many contexts, the use of TV and radio served as an alternative strategy for remote learning. However, the absence of conducive conditions for a learning environment, such as a place to study and access to learning materials, limited the level of engagement from students and their ability to learn effectively.

School closures and the ineffectiveness of remote learning responses are estimated to have increased learning poverty (defined as the share of children who cannot read a simple text with comprehension by age 10) from 57% to a staggering 70%.

In response to these challenges, as of earlier this year, less than half of countries had started implementing learning recovery strategies at scale to help children catch up, with only one percent of Covid-19 stimulus packages in low- and lower-middle income countries allocated towards education.

There’s no question that governments must double down on their efforts to mitigate the learning losses from the pandemic.

Private education

As of 2020, 19% of primary school enrollment and 27% of secondary school enrollment globally was provided by a multitude of non-state actors, including NGOs, faith-based schools, public-private partnerships, local community-lead organizations, privately run chains and low-cost private schools.

This number rises further when we look at Central and Southern Asia, where non-state enrollment is as high as 36% in primary and 48% in secondary education, and in pre-primary education in low-income countries, where over 55% of children are served by private operators.

Considering the prominent share of the non-state sector as a provider of education services in low- and middle-income countries, as well as the magnitude of the obstacles that arose as a result of the pandemic, it is essential to consider the role of these actors in contributing towards the mitigation of learning losses.

The non-state sector has provided education to over 350 million children across the world. It has also contributed to much of the innovation that Brookings has identified as being crucial in leapfrogging educational systems: innovative pedagogical approaches, smart use of technology and data that allows for real-time adaptation, and teacher training and mentorship.

Furthermore, non-state actors support public education systems through ancillary services such as technology, assessment systems, supplementary tutoring, and the textbook industry, which also help accelerate the urgency to address equitable access to technology and digital learning.

Education enterprises

An example of such private sector innovation is Varthana, India’s largest lender to non-state K-12 schools. Varthana provides loans for schools to invest in equipment, technology, teacher training, and even basic facilities like toilets.

When the Covid-19 pandemic forced schools to close, Varthana stepped in to help them put together online learning plans that would be accessible on the most basic phones. By helping schools organize live online classes as well as asynchronous learning that could be delivered over low-tech devices, Varthana has helped students in 1,300 schools continue their education.

During this period, Varthana received critical support from investors such as the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation and Kaizenvest, an education-focused emerging markets asset manager.

“For mission-driven enterprises, bringing impact investors on board ensures an immediate alignment of purpose amongst all the stakeholders, and that goes a long way in increasing the speed and agility of the enterprise,” says Nirav Khambhati, a managing Partner at Kaizenvest.

Kaizenvest continuously searches for salient practices within portfolio companies that can be passed onto other portfolio companies that are in a non-competing space. An example of this was the workshops conducted by Kaizenvest with their investees to brainstorm strategies seeking to mitigate the impact of lockdowns.

In Zimbabwe, where more than 4.6 million learners suffered disruptions in learning as a result of the pandemic, the Higherlife Foundation helped develop strategies to keep students engaged, complementing the catch-up approach implemented by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education.

The foundation partnered with service providers to help deliver lessons and daily check-ins via WhatsApp as well as empower caregivers and tutors to teach students in contexts with limited access to internet and devices.

Financier network

The odds are stacked against the most disadvantaged students: learners from marginalized communities and those who are striving to overcome the learning losses in low-and-middle income countries.

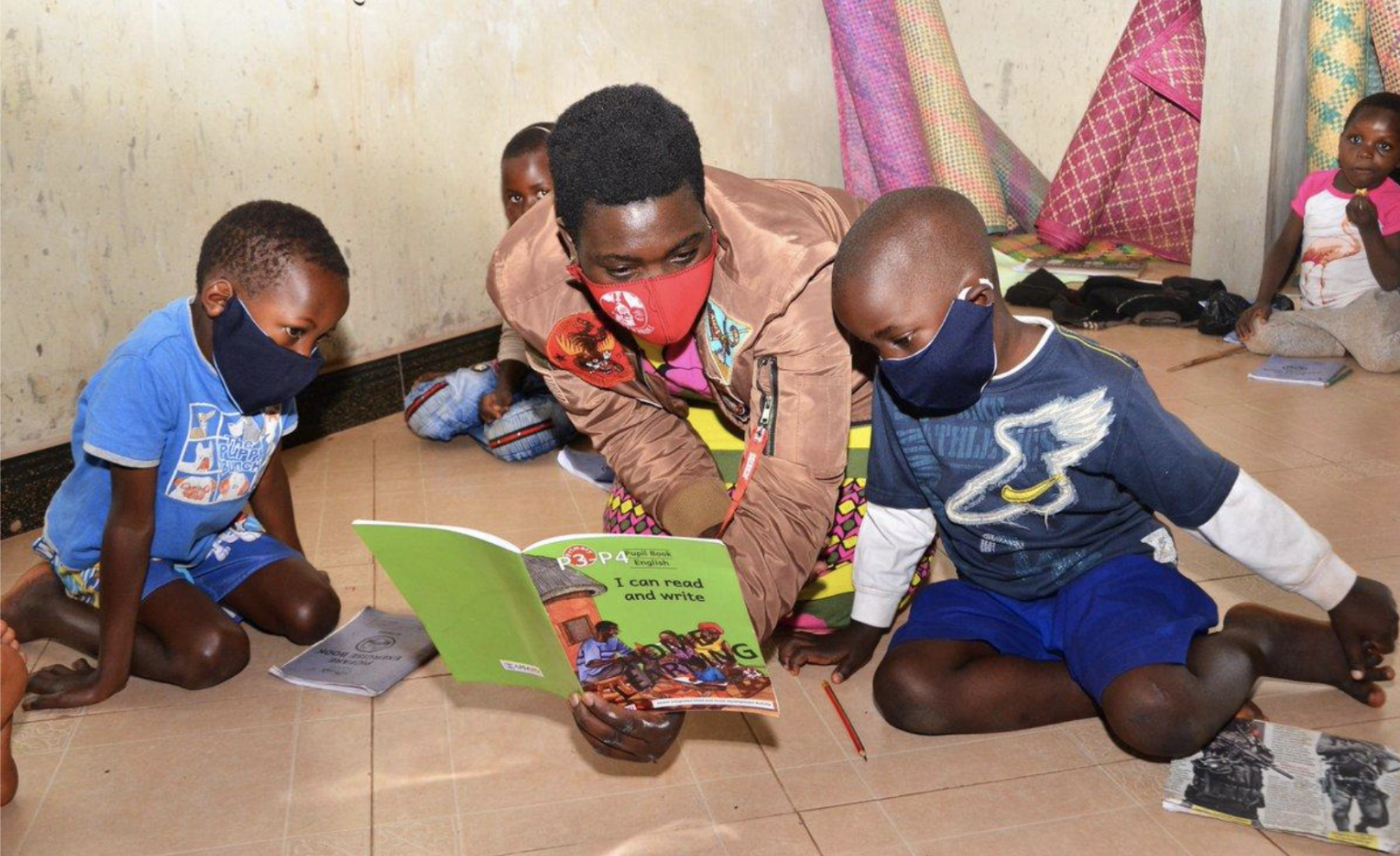

In a recent New York Times article, citing the reopening of Uganda’s schools, where approximately 45% of secondary school provision comes from non-state actors, the reporter interviewed David Atwiine, age 15. Although he started selling masks in the streets of Kampala after the shutdown was imposed, David claimed: “I must return to school and study.” Like David, there are millions of children that rely on the support of a community to be able to return to school.

By “community,” we mean the parents, caregivers, neighbors, but also governments, education providers and investors. A central piece in the recovery puzzle will be the ability to draw in more private capital from investors, equipped with innovative financing instruments to back solutions with high impact potential for enhancing equitable outcomes.

That is precisely what the Education Finance Network is trying to do. Our members include foundations, donors, impact investors, practitioner networks, and research and advisory organizations, all gather around a vision of a global education sector where disadvantaged learners have equal access to quality education and where state and non-state education actors work together, relying on open dialogue, collaboration, and evidence around what works best, to provide quality education and supporting services for disadvantaged learners.

USAID, Kaizenvest, DFC, the Higherlife Foundation, and the Brookings Institution, referenced in this article, are all members of the Education Finance Network and integrate its Steering Committee.

Given the magnitude of the problem we face, we are calling on non-state actors to raise the stakes by pushing the education community to find the right tools and alliances in response to this urgent need, especially considering that this is a challenge where we cannot afford to fold.

If you’d like to learn more about the work of the Education Finance Network and apply for membership, please reach out to [email protected] to know more.

Kusi Hornberger is a partner at Dalberg Advisors, Inês Charro is the Education Finance Network program manager and Nirav Khambhati is a managing partner at Kaizenvest. They are based out of Washington D.C, New York City and Mumbai, respectively.